Canton at War: The Awakening of a ‘Sleeping Giant’

By Jeffrey PicketteEditor’s note: The following is the first installment of a three-part series that looks into what life was like for Canton residents during World War II. The first part deals with the home front. Part two deals with Canton’s contributions on the frontlines in both the European and the Pacific Theaters of war. Part three deals with the aftermath of WWII.

***

Canton native Edward Estey remembers getting choked up when his Boston-bound train passed through Canton Junction in early 1944.

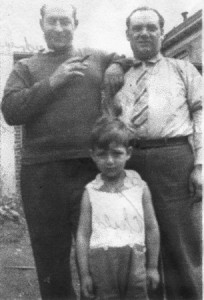

Carmine Andreotti, back right, Tony Uliano, back left, and Tony Andreotti, in front, are pictured in this 1939 photo. The younger Andreotti is today the town’s veterans’ agent.

Estey, only 18 years old at the time, had just completed his basic military training with the United States Army at Fort Meade in Maryland and was en route to Boston where he would ship out and be sent to Europe to take part in that theater of World War II.

“The tears came to my eyes,” Estey recalls. “I was so near, yet so far.”

***

World War II impacted Canton — a town of just 6,314 according to 1940 federal census figures — more so than perhaps any other war fought in this nation’s history. 853 men and women, representing almost 14 percent of the town’s population, served in the armed forces in some capacity during the Second World War.

“You very seldom saw anybody from 18 years old to 35 years old anywhere,” Tony Andreotti said.

Andreotti, who is now the town’s veterans’ agent, was just a young boy living in Canton during WWII. He reasons that of the town’s 6,000-plus citizens, half were male and nearly all of the 853 who served from Canton were male, so the town’s male population took a significant hit.

At the dawn of the war, Canton was still recovering from the Great Depression. Those interviewed describe the town as a close-knit community where life moved at a slower pace than it does today. At ten minutes to 9 the fire station blew a whistle, as Estey remembers, telling children it was time to head home for the night. There was less development and more open fields. Residents rarely ventured far from the town’s borders.

The war in Europe effectively started when Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939. 737 men registered in a peacetime draft held at Upper Memorial Hall over a year later on October 16, 1940 — signs that America, which at this point was holding out from entering the war, was at the very least preparing for the possibility of becoming an active participant.

“That was [over] 1,000 miles away,” Estey said. “We were just kids. We were thinking about school, baseball and things like that. [The war] really wasn’t at the top of our minds.”

This of course changed after the events that took place on a fateful Sunday morning — December 7, 1941 — when the Japanese attacked an American naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, officially bringing this country into the war.

Arline Love, who moved to Canton from the town of Braintree in 1940, remembers hearing the news of Pearl Harbor come in over the radio. She was down in the basement of her Canton home with her father, Walter Love, who was making toys for Christmas, as she recalls.

The country, Canton included, soon mobilized, with troops leaving for the battlefields in the Pacific and in Europe. The home front was mobilized in a sense as well.

“Everybody had to buckle right down,” Love, now in her 70s, said.

Children would pull wagons and carts filled with paper or scrap metals for the various drives held around town. First-aid courses were given and care packages for the troops were assembled. Ed Piana recalls knitting squares that became parts of blankets used by the Red Cross.

“The children were involved [in the effort] as much as anybody else,” remembers Piana, who was 11 at the time of Pearl Harbor.

Women were active in the war effort as well. In town, many women worked at the Neponset Woolen Mills, which was located where the River Village condo development stands today, or at the Draper Mills on Washington Street. Some women from Canton even went to work at the Fore River Shipyard, which was located in Braintree and Quincy.

Ann Piana’s father, Edward Collins, was ill during the war, so her mother, Anne Collins, went to work at the Draper Mills to help support the family.

“She took very good care of us,” Ann Piana said. “She was a forward-thinking woman and a strong woman.”

Other women, like Arline Love’s mother, Alice Love, volunteered at the Boston City Hospital or were active with the Red Cross.

In the later years of WWII, German prisoners of war were bused into town to work at the Springdale Finishing Company near Pine Street.

“I never talked to them, but I would suspect they were happy to be here rather than out serving on the Eastern Front,” Ed Piana joked.

Part of the war effort on the home front also included the American people scaling back from using what had come to be considered everyday necessities, as these products were in short supply during the war.

Meat, sugar, and butter — nearly all who were interviewed mentioned how Oleo Margarine replaced real butter — were rationed, as were other non-food items like gasoline, tires and shoes among other things.

Love’s father was the chairman of the rationing board in town and she said as a result, he was the “most unpopular man in Canton.”

“It was probably one of the more thankless jobs in the war,” she continued.

Rationing might not have helped a lot of businesses in Canton, but Andreotti’s father, Carmine, was a shoe cobbler and his National Shoe Repair business on Washington Street boomed during the war.

Andreotti said that his father had an “uncanny memory” and that before and after the war he could remember which pairs of shoes belonged to each customer. It did not matter if one family member had dropped off the shoes and another came to pick them up. He did not have to distribute tickets or pick-up receipts.

But during the war, Andreotti recalls that his father had to finally “break out the tickets” as “mountains” of shoes were left lying around the shop.

As all of this was going on, there was a fear that the United States could come under attack. On the west coast it would most likely have been an attack from Japan, but in Canton and in other cities and towns along the east coast, an attack would have most likely come from Germany.

“No one knew where we were going to be attacked next,” Love recalls.

It was commonplace for people to paint the top of their windows or pull “blackout curtains” over the windows to prevent light from shining at night. For the same reason streetlights were shaded and the top of headlights on cars were painted black.

Air-raid drills were held at school. In 1941 and 1942, Estey and classmate John O’Connor took the Friday night 7 to 8 p.m. shift at a lookout tower on a hill on Pine Street to watch for enemy planes. Ed Piana remembers that the historic Canton Viaduct was guarded as well.

Andreotti said at the time people believed an attack could be imminent, but, in retrospect, he said he did not “know how realistic that was.”

Still, whether it was participating in scrap drives or having to forgo the use of butter because of rationing or preparing for a possible aerial attack from enemy planes, “there wasn’t a single day,” as Andreotti remembers, “that you didn’t know there was a war [being fought].”

“Our lives were changed immediately,” Love added. “I’m not saying that in a complaining way because we didn’t look at it that way. We didn’t look at it as hardship. We looked at it as doing what we needed to do to protect the country.”

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=3072