True Tales: They prayed at Punkapoag

By George T. ComeauLast week we celebrated Thanksgiving, and while the roots of the traditional story are well told, there are elements of the contact between the native population and the Puritans that heralded the end of a civilization. In Canton, there are abundant reminders of what once was, but could never survive.

John Eliot preaching to the Indians as depicted in an unfinished sculpture by John Rogers in 1887 (Courtesy of the author)

The facts are startling: Put simply, after the Europeans arrived in “their” new world, they brought diseases that decimated the native population. By the mid 1630s the population of the Massachusetts tribe had been reduced from over 24,000 to less than 750. By 1646, the European settlers had brought more than 24,000 people to live here in New England. Against this backdrop of disease, death and destruction came a new system of laws, religion, and ideology that would forever change the people who once lived here.

John Eliot was a pastor at the First Church of Roxbury from 1638 until he died in 1690. In those 52 years, Eliot became well acquainted with Canton’s first settlers. It is from Eliot that we learn the most about the challenges of Christianizing the native population. The goal was to “civilize” the pagans and then transform their religious beliefs in such a way as to save their souls. Eliot took his work most seriously; it was his translation in 1663 of the bible into the Algonquin language that would be the first bible printed in America.

It started with good intentions. The idea was that, in order to save these savages, Eliot would need to isolate them from the burgeoning English population. For good reason, Eliot became known as the “Apostle to the Indians” as he found it his God-given duty to convert the natives to Christianity. As he noted in his memoirs, Eliot gave serious thought as to what to do with these people — “the dregs of mankind, and the saddest spectacles of misery of mere men upon earth.” Eliot goes on to describe the natives as “perishing, forlorn outcasts” who “inhabited dark and gloomy habitations of filthiness in uncleane spirit.”

In 1646, the General Court of Massachusetts passed an “Act for the Propagation of the Gospel amongst the Indians.” It was soon thereafter that supporters in England formed “A Corporation for Promoting and Propagating the Gospel of Jesus Christ in New England.” The people in England dedicated more than 12,000 pounds sterling as an investment in the cause.

Between 1646 and 1675, a series of Praying Towns were created to allow the native population a place to live, worship, and acculturate to the ways of the English. The old ways of the hunter-gatherer would be disavowed, as would the traditional dress ceremonies, cultural activities, education and anything else seen as “savagery.” Natick was the first Praying Town, and land in present-day Ponkapoag was the second established town.

Eliot planned his second Praying Town for the Neponset Indians, writing in a letter that they “desire to make a town named Ponkipog, and are now upon the work … Though our poore Indians are much molested in most places in their meetings in way of civilities, yet the Lord hath put it into your hearts to suffer us to meet quietly at Ponkipog for which I thank God, and am thankful to yourself and all the good people of Dorchester. And now that our meetings may be more comfortable and favorable, my request is that you would please to further these two motions: First, that, you would please to make an order in your towne record, that you approve and allow ye Indians of Ponkipog there to sit down and make a town. My second request is that you would appoint fitting men who may in fit season bound and lay out the same and record it also. And thus commending you to the Lord, I rest.”

Eliot’s letter to Major-General Humphrey Atherton asked the leaders of Dorchester to “lay out” land for the Ponkapoag Plantation — in essence, America’s first “Indian reservation,” a place where he could select and move tribal members in order to control and acclimate them to the ways of the white man. What else can we call it? Eliot felt that it was important to save these souls, to gather up all the Indians he taught to practice Christianity, and move them to one place under the watchful eyes of their guardians so that they could practice the ways of a Christian.

At a town meeting held in Dorchester on December 7, 1657, it was voted that the town give a plantation to the Indians at Punkapog, and also that “Hon. Major Atherton, Lieut. Clapp, Ensign Poster, and William Sumner be desired and empowered to lay out the Indian Plantation at Punkapog, not exceeding six thousand acres; and that the Indians should not alienate or sell their plantation or any part of it.” The gist of the deal was that the English settlers would give some land to the praying Indians, land that they could neither lease nor sell to anyone, yet could simply live on. To ensure the safety of the Indians, the following year the provincial government appointed guardians to “watch over their interests.”

The plantation boundaries would be a critical understanding between the government that was extending “portions of our wilderness territory, the parts of which had so recently been regarded by the savages as their unchallenged territory.” The bounds were closing in, and by early 1667, Josias, then sachem of the Massachusetts tribe, requested a deed for the 6,000 acres at Punkapoag. In May of that year, a committee was formed and they visited the plantation, but no plan was drawn or deed produced.

Eventually the boundary of the plantation was drawn up, and John Butcher surveyed a map in 1696, the legal description of which amounts to approximately 811 words — roughly described as extending substantially from Ponkapoag Pond on the east nearly to the Neponset River on the west, south to the present-day Canton Viaduct, and east to modern Stoughton and then back to Ponkapoag Pond.

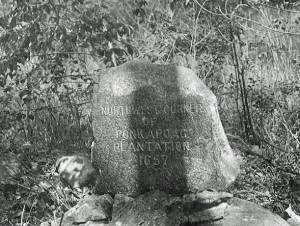

The marker in the woods off Elm Street denoting the “northwest corner of the Ponkapoag Plantation” (Courtesy of the Canton Historical Society)

Today the boundaries of the plantation are hard to discover, but in at least two or three instances, hidden markers denote the corner boundaries of the land that confined these indigenous people. In the woods off Green Street is a stone monument inscribed as the “Northwest Corner of the Ponkapoag Plantation.” In the backyard behind a house on Fuller Street is another etched marker. And in Stoughton, near Glen Echo Pond, is a third. For several years, Dwight Mackerron, a Stoughton historian, has been hiking the boundary of the plantation searching for clues as to the modern-day bounds. Over the years, surveyors and historians have worked to map the area and gain a fuller picture of the village that would become Canton.

In Eliot’s Punkapoag, he would preach twice a month to the collected families that had been moved from the more populated area along the banks of the Neponset River where it fed the Dorchester Bay. The area was most likely between Lower Mills and the present-day Morrissey Boulevard. These “sermons in the wilderness” were memorialized in paintings and in sculptures and hold a special place in early Massachusetts history.

A friend of Eliot’s, Daniel Gookin, was appointed in 1656 by legislative enactment as the superintendent of the praying Indians. It is from Gookin’s accounts that we have some sense of what the colonists’ perceptions were of the natives. “The customs and manners of these Indians were, and yet are, in many places brutish and barbarous in several respects…,” he writes. “They take many wives; yet one of them is the principal or chief in their esteem and affection. They are very revengeful … addicted to idleness, especially the men who are disposed to hunting, fishing, and the war … The men and women are very loving and indulgent to their children.”

Gookin visited the place called Punkapaog or Pekemitt, writing, “The signification of the name is taken from the spring that ariseth out of the red earth.” Gookin’s description of the area is familiar: “There is a great mountain, called the Blue Hill, lieth north east from it about two miles … this is a small town, and hath not above twelve families in it; and so about sixty souls. Here they worship God, and keep the Sabbath … They have a ruler, a constable, and a schoolmaster. Their ruler’s name is Ahawton; an old and faithful friend to the English.”

In 1674, Gookin wrote of his accounts in “Historical Collections of the Indians in New England,” which was published after his death. These accounts are quite detailed and paint a brief picture of the way of life in the Ponkapoag Plantation. “In this village, besides planting and keeping cattle and swine, and fishing in good ponds, and upon Neponsitt river which lieth near them; they are also advantaged by a large cedar swamp; wherein such as are laborious and diligent, do get many a pound, by cutting and preparing cedar shingles and clapboards, which sell well in Boston and other English towns adjacent.”

Far from idyllic, it turns out that a Ponkapoag Praying Indian would trigger a war that would bring an end to peace between the natives and the Puritans. Dark days were ahead for the Indians at the plantation. The story continues in the next installment as we literally tear open the graves of the Neponset Indians of the Massachusetts tribe praying at John Eliot’s Ponkipog.

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=17630