True Tales: A Memorial to Freedom

By George T. Comeau

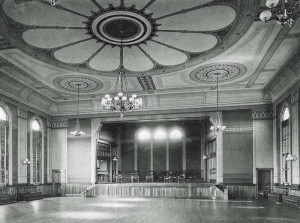

Memorial Hall in 1879 as it appeared just after completion (Courtesy of the Canton Historical Society)

When it was built, it was the largest public structure in Canton. A grand memorial to the men of the Civil War, we named it Memorial Hall. All across America the soldiers who fought in the War Between the States were beginning to pass away, and for the great masses of men who fought, there was a certain need to mark the great sacrifices that were made to keep the nation as one.

The war ended in 1865, and within two years the soldiers from Canton began gathering annually in encampments to provide a social structure to the shared experience that had brought them together during those hostile years. General Charles Devens Jr. of Boston formed the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) in Massachusetts. The purpose was to “preserve those kind and fraternal feelings which have bound together the soldiers and sailors who have stood together in many battles, sieges, engagements and marches.”

Across the nation more than 8,600 community-based GAR posts were formed, including more than 200 across Massachusetts alone. In Canton, the soldiers formed GAR Post 94, known as the Revere Post in commemoration of the loss of the two nephews of Paul Revere who hailed from Canton and died on the battlefield. Membership in the GAR was limited to those men (and a few women) who served in the Union Army, Navy, Marine Corps, or Revenue Cutter Service during the Civil War. As such, the GAR was destined to eventually cease existence, which it did in 1956 when Albert Woolson, the last veteran of the war, died at age 106.

Canton had an extremely strong connection with the Civil War, and the Revere Post was an influential part of community decision-making. Building a memorial to the memory of the lost men from Canton began in 1878 — 13 years after peace had been restored. A committee of five men were selected and instructed to take a deed of land donated by the wealthy local philanthropist Elijah Morse and erect a building thereon to be called Memorial Hall. The committee started work immediately, selecting the architect, Stephen C. Earle of Boston.

Earle was a fairly well-accomplished architect who specialized in academic, cultural and commercial buildings, churches — 23 in Worcester alone — as well as firehouses, private homes, and apartment buildings. Earle was a veteran of the Civil War, having served as a medical corpsman in the Union Army. After the war, Earle traveled through Europe to essentially gather the visual cues that would become hallmarks of his work back in America.

Earle was heavily influenced by Gothic, French Second Empire, Neoclassical and Romanesque styles. In fact, the critics of the day described Canton’s Memorial Hall as “Modern Gothic.” There are Lombardic and French styling elements throughout the façade of our great building. Wherever possible local materials were used, but predominantly the building is made of red brick trimmed with Longmeadow freestone (the same stone as that of the Trinity Church at Copley Square) and contrasted with bands of black brick laid in black mortar. There is even a hidden carving of a wise old owl above the portico.

The building is massive in scale, made even more impressive when you consider it was built in the late 19th century for a town with a population of approximately 4,000 people. The six front stairs alone are 20 feet long and made of hammered Concord granite. Covering 6,500 square feet, its extreme height is 80 feet above the finished grade. The interior space when it was built was equally impressive; the second floor was 26 feet from the floor to the ceiling.

To look at Memorial Hall in Canton, imagine a great church, for in essence that is the historic form that the building takes. The building forms a cross with a center aisle that originally divided the entire structure. The altar, if you will, was a large stage that extended the entire back of the hall. The front of the building projects out, extending as if a tower could rise to a belfry high above the building. When it was built, large gothic trimmed chimneys occupied the four corners of the structure. Look closely beyond the first bay of windows at each corner and you can see the vestiges of the chimneys as slight bump-outs in the exterior walls.

Originally the building was intended as a community center where all manner of entertainment and meetings would be held. On the first floor, as you entered to your right, was a small ticket booth that sold admission to minstrel shows, concerts, basketball games, dances, and exhibitions. The first floor was dedicated to public offices, with the town clerk, selectmen, and treasurer on the right and the public library on the left side of the building.

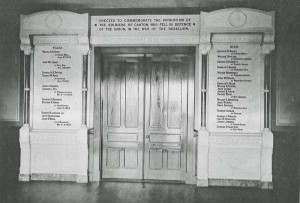

The centerpiece of the first floor is of course the memorial tablets, a gift of Elijah Morse. It is likely that this was a very special gift for Morse, as he had enlisted in the Union Army and was part of the 4th Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteers and had served under General Butler in Virginia and under General Banks in Louisiana. At the time that Memorial Hall was built, Morse was a member of the Massachusetts House of Representatives and extremely wealthy as a result of his business interests.

The left-hand tablet bears the names of those killed in battle, with the date and place where they were killed. The 11 names, ordered by the date they were killed, are etched into the cream-colored marble. The names on the right-side tablet are those servicemen who died of disease or wounds and not directly in battle. These 19 names and locations evoke the distant places where these men died in horrendous pain so far from home. All of the names are etched in light-veined Italian marble.

Stepping back from the tablets and truly taking in the memorial in its entirety is critical to the message. At the top, over the door is the inscription: “Erected to commemorate the patriotism of the soldiers of Canton who fell in defense of the Union in the War of the Rebellion.” And just below is the motto: “It is sweet and honorable to die for one’s country.” This motto was taken from a line in a Roman lyrical poem by Horace in which citizens are encouraged to develop martial prowess to terrify enemies of the republic. Ironically, this same motto is inscribed at the Confederate cemetery at Manassas National Battlefield Park.

The memorial was designed by Earle, but carved and built by John Evans of Boston. Evans was a well-known carver and his works are in the Washington Cathedral, Trinity Church in Boston, and the landmark Church of St. John the Divine in New York City.

Evans used delicately mottled marble, brought from the Echaillon quarries at Grenoble, France. The source for the marble in France was the same as that of the Arc de Triomphe and is considered one of the finest sources of limestone in Europe. Four columns support the canopy and are made of highly polished Red Lisbon marble, and dark Tennessee marble make up the plinths at the base. Look closely and you will see the arms of the Union in the medallion of the canopy and arms of the commonwealth of Massachusetts between branches of laurel and olive. Foliage and rosettes complete the artwork.

Upon completion, Memorial Hall was constructed and dedicated at a cost of $30,961. On October 30, 1879, hundreds showed up to listen to the speeches of the governor and secretary of state, as well as local politicians from around the county. From that point forward, Memorial Hall was dedicated to the people of Canton.

The memorial tablets in honor of Canton’s fallen Civil War heroes (Courtesy of the Canton Historical Society)

At almost 135 years old, we have taken great care of this building, for it is unlikely that public funding or support could ever be garnered to build such a building again. Today, the building no longer holds a social use but is purely governmental in every respect. The music and dancing is merely an echo of the past as the interior is transformed into something far removed from its original use.

The basement once held a firing range for the Canton Police Department. At the far right of the enormous space was a lead-lined, sand-filled room where patrolmen would regularly practice firing their weapons underneath unsuspecting taxpayers filing their yearly payments. Large vaults too heavy for the southern pine floors lined the spaces shared with immense boilers. Today, modern office space takes up most of the at grade floor. The third floor too has changed, and the hall, which unbelievably held 1,050 people comfortably, is now home to the selectmen and various other town boards. Dressing rooms that were used by vaudeville actors are long gone, replaced by generous meeting spaces.

In the end, let’s not lose sight of what Memorial Hall was meant to be — that place where we could remember these men who died for their nation. The names engraved in the finest marble should be forever in our hearts. And we are assured that our men of Canton died in a just and righteous cause. Lincoln’s words echo here: “From these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion — that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain — that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom — and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=18853