An Atlantic Odyssey Parts 1 & 2

By George T. ComeauHarold Winslow cut the very figure of the dashing sea captain that he was. At 45 his shock of black hair swept up from his prominent forehead, and his eyes still had the twinkle of wistfulness for the Atlantic Ocean.

Winslow thought back on his career and smiled softly to himself, yet his body winced with pain. In a posh New York City apartment, Captain Winslow sat at the kitchen table and reminisced upon his remarkable life.

Born to Charles and Anna Winslow in 1893, Harold grew up in the shadows of the great shipyard that would make Quincy famous. Always with an eye on the ocean, the Winslows lived within walking distance of the Town River Bay inlet, and Harold likely saw the great ships slip from their berths at the Fore River Shipyard. With each sound of the ships’ horns Winslow would grow closer to the sea.

There were plenty of neighborhood kids who felt exactly the same. In fact, one of Winslow’s closest childhood friends and the person who would be his best friend for life was Giles Stedman. Both Stedman and Winslow would follow incredibly similar paths, and Stedman would be with Captain Winslow at the very end.

The Winslow family moved to Canton sometime before 1906. Wadsworth, Harold’s older brother, graduated from Canton High School in 1907, and at the same time, Harold was attending the Crane School. There was a branch of the family already living in Canton, and the move from Quincy made sense — the shipyards were dirty and noisy and a home in the countryside was a welcomed change.

The family lived on High Street; Charles Winslow’s brother, Wadsworth, lived a few houses away. The walk through Canton Center to the Crane School was a short distance from their home. In 1908, Harold graduated from elementary school and later that year he entered Canton High. A photo from his graduating class shows a well-dressed young man, looking straight into the camera. After two years at Canton High, Winslow attended the Massachusetts Nautical School in the Boston Navy Yard. It seems that while his parents were content in Canton, the destiny of the sea was calling.

Harold Winslow, left, in his eighth grade graduation photo from the Crane School in 1908 (Courtesy of the Canton Historical Society)

In 1891, the Massachusetts Legislature created the Massachusetts Nautical Training School. It would become the largest state maritime academy in the United States. In 1910, however, the class size was fairly small and the age at which a boy could enter was 16. The mission of the school was to “offer instruction in seamanship, navigation and marine engineering to the sons of the citizens of the commonwealth.” Graduates would be qualified for service as deck and engineering officers in the newly formed American merchant marine.

A report of the day aptly describes the type of student who would enroll at the Nautical School: “At the present time a life at sea appeals more than ever before to the serious and deliberate young man, the lad who cares less for adventure and looks upon the mariner’s life as a high and useful calling, a life worthy of one’s highest efforts.” This description fit Harold Winslow perfectly.

As the civilian auxiliary of the United States Navy, experienced men who had strong ties to military service did the training at the Massachusetts Nautical School. In the buildup to Word War I, America literally transformed itself from a nation where maritime shipbuilding was inconsequential to a place of leadership among developed nations. By 1919, this nation had “more ship workers, more shipyards, more shipways, more vessels under construction, and turned them out more rapidly and in greater numbers than were issued from all the other shipyards of all the world.” Winslow was entering the Nautical School at a time of tremendous growth and buildup in American maritime superiority.

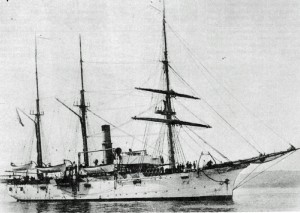

The number of cadets enrolled in classes at the Navy Yard was limited to the fact that there was a single training ship, the U.S.S. Ranger, on loan from the Navy to the commonwealth. The school was heavily dependent upon the Navy for goodwill and support. While each town was assessed a small fee for any residents who attended, the bulk of the ongoing expenses came from the state budget. At the center of the school was the training ship.

The year before Winslow entered the school, the Navy loaned the U.S.S. Ranger as the nautical training ship of the state. This was a modern ship with state-of-the-art systems and design. At 177 feet long and with a 22-foot beam, she drew 14 feet. What made her a modern ship for warfare was a Marconi wireless telegraph, submarine signal equipment, a steam capstan and a modern steam engine. Throughout her 33-year history she remained in educational use until a transfer of service in 1942, when she was transferred from the Navy to the United States Maritime Commission.

Today, the Massachusetts Nautical School is known as Massachusetts Maritime Academy and is one of the premiere training schools in the country. Back in 1910, the organization was just as impressive. The ship accommodated up to 116 cadets, and life was organized around the ship berthed at North End Park from October through April. The spar deck was used for study and recitation, and during the harsh winter months in port there were no indoor spaces for drill or recreation. This was a very rigorous two-year education.

During his first year of training, the Canton boy was given practical instruction in seamanship and engineering duties.

Winslow likely participated in the “Summer Cruise,” when the sea routine would test the training of these young boys. The cruise would begin with a preliminary nine-day cruise in and about Massachusetts Bay, followed by an extended tour to ports in France, England, Spain, and Portugal before returning home via Bermuda. Imagine the experience of one of Canton’s most prized young men as he set his course against the North Star.

Graduating in March 1912, Winslow went on to join the U.S. Navy around 1914 at the start of hostilities between the United States and Mexico. Staying through World War I, Winslow was a Boatswain’s Mate second class aboard the U.S.S. Nevada, and in 1919 he served as an ensign aboard the U.S.S. Choctaw. Leaving the Navy at the rank of lieutenant, he briefly was reported as an agent of the United States Secret Service.

The real distinction for Captain Winslow began in 1922, when he joined United States Lines as fourth officer on the President Polk. After the war a number of ships had been captured from Germany as war prizes, and the United States Shipping Board was responsible for distributing these ships for American merchant services. Winslow, in fact, had been an inspector for the Shipping Board, and so when United States Lines was formed to take over several captured ships, he fell into the right company of service.

United States Lines was the premiere American shipping company. Naval historian Bill Lee explained that there was a “deliberate strategy not to compete with German, British and French lines; the U.S. lines were smaller and more comfortable and stressed clean, comfortable and luxury services — over speed and making records in transatlantic crossings.” Winslow would be responsible for some of the finest American cruise ships afloat in the early 20th century.

It was a tight community, modeled after the Navy, from which most of these men came. Winslow found himself again in the company of his dearest friend, Giles Stedman. Time and again, these two men would either serve together or find solace drinking in the bars around the port of New York. Both men were true naval heroes for their exploits across the Atlantic and more particularly for saving lives.

It was the heroic rescues that made headlines, and on a frigid December morning Winslow found himself staring into death as he navigated a small lifeboat toward a sinking schooner. The storms of 1929 had been particularly vicious and entire fleets were being lost during that year. Aboard the United States Lines cruise ship Republic, Captain A.M. Moore turned to Winslow, his chief officer, to lead a historic rescue. As part of a fleet of schooners being lost to ferocious winds and historic seas, if these men were not saved, an entire community of men would die, leaving women and children as their only legacy.

And in that apartment in 1938, Winslow sat in pain, contemplating a way to end his own life, and thinking about that rescue not ten years ago where he was the difference between life and death for 11 men …

Click here to read the thrilling conclusion of the 1929 rescue and more on the life of Captain Harold Winslow.

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=19320