True Tales: Full of Hot Air

By George T. ComeauThey came in droves to hear their neighbor speak. Packed into the parish hall that February night, young and old sat shoulder to shoulder as Henry Helm Clayton walked to the front of the room. Wearing simple gold-rimmed glasses and a winning smile, Clayton began describing “How It Feels to Fly.”

“How It Feels to Fly” lecture pamphlet from Canton, 1911 (Courtesy of the Canton Historical Society)

Clayton spoke softly: “We touched the ground and the race was over … In 40 hours we had traversed the greatest distance in a straight line ever traveled by a balloon in America, and had won the race. In an air line from St. Louis, the distances 872 miles; but in making this distance, since the course was not perfectly straight, we had traveled 932 miles … In all this distance we had found it necessary to inquire as to our geographical position only once.”

In 1911, there were few if any people in Canton who knew what it felt like to fly. The aviation industry was still in its infancy, and Clayton played a unique role in helping shape the science needed to understand flight. This man of science wrote volumes on weather observations made right here in Canton. It was ballooning, however, that made him a world-recognized star. In the Aero Club of America, Clayton held license number 30, making him the 30th person in the United States to hold a pilot’s license.

Clayton was born in Murfreesboro, Tennessee, on March 12, 1861. One of the earliest students in America to take up the study of meteorology, Clayton was a giant in the birth of scientific weather and its connection to aviation. Professionally, Clayton began his studies at the University of Michigan’s Astronomical Observatory in 1884 as a student assistant. Graduating around 1885, Clayton took up a position at the Harvard Observatory, which led to his being appointed as a full-time observer at the Blue Hill Meteorological Weather Observatory here in Canton.

While there is some dispute as to whether the Blue Hill Observatory is in Canton, there is evidence to suggest that in the basement under the stone fortress is a small pin serving as the dividing line between Canton and Milton. Clayton always declared that he hailed from Canton and as such he is one of our more prominent citizens. For three years he worked for the fledgling United States Weather Bureau as a local forecast official. Yet the connection to the Blue Hill Observatory was strong enough to bring him back from 1894 through 1909 as the meteorologist at the observatory.

It is likely that Clayton’s time in Canton high atop Blue Hills earned him the nickname “kite king.” It was the huge volume of study surrounding the movement of the atmosphere that occupied large portions of time at the weather observatory. Visitors today can see the location of the “kite shed” where Clayton controlled enormous hand-made contraptions to take weather-sounding instruments into the atmosphere. The Blue Hill Box Kite was invented by Clayton, as well as several unique and new measurement devices that yielded the best early studies of air currents and temperature variations that would forever change aviation history.

Clayton was a scientist, and his papers, letters and research attest to his enormous contributions. Discussions of the cloud observations above Canton became seminal studies shared with scientists across the globe. This man authored hundreds of articles and became a pioneer in the use of kites to study airlift, currents, and the movement of the atmosphere high above the earth. In one particular study in 1893, Clayton claimed that the weather could be predicted in cycles, which closely follow the highs and lows of barometric activity. In fact, we use the same science today to predict the storms and sunny days that keep our summer picnics safe from rain.

In the early 20th century, the gentlemen’s sport of “ballooning” was in vogue, and Clayton, with his unparalleled knowledge of airflow and currents, was a much sought-after companion for the competitive balloon races that focused the nation’s eyes on the clouds. The owner of the New York Herald sponsored the second Gordon Bennett Cup distance race in 1907. The previous year the race was held in Paris, France. It is likely that Clayton was there and may have even participated, for the second year along with Oskar Erbslöh they would control a spectacular record-breaking race.

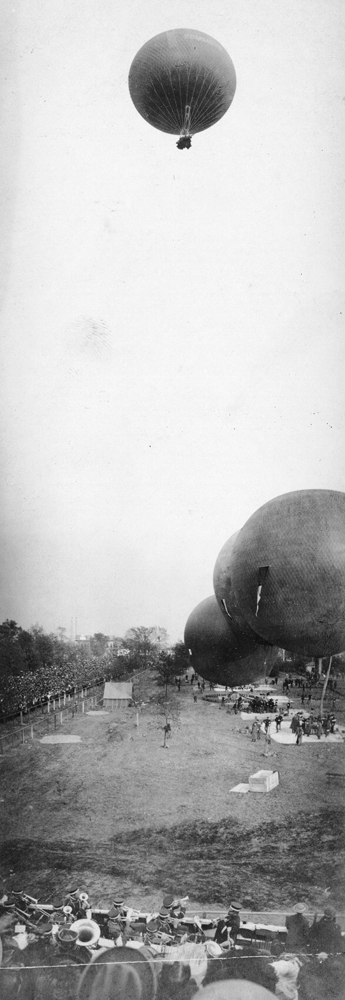

Ballooning was big business and nations vied for the bragging rights, not unlike the America’s Cup today. The race featured nine balloons from Germany, England, America, and France. The teams set off from St. Louis on October 21, 1907. Representing Germany in the war balloon called Pommern, Clayton and Erbslöh took off at 4 p.m. and immediately took the lead.

Pommern launching on October 21, 1907, in St. Louis (Courtesy of the Missouri History Museum, St. Louis)

In an article for the Atlantic Monthly, Clayton wrote extensively of the amazing voyage. “During the 40 hours that we were in the air we lived in a basket two and half by three feet. In these narrow quarters there was not much room for freedom of motion, yet neither of us felt cramped for room, on account of the excitement and novelty of the voyage, and the fact that we were much engaged with the details of the management of the balloon and with the problem of keeping track of its course. We were also busied in trying to keep informed of the direction and speed of the air currents above and below us.”

The newspaper accounts were sensational. “About 3 o’clock yesterday afternoon they were uncertain of their bearings and dropped within 500 feet of the earth and called to a woman who stood near a farmhouse. She was greatly frightened, and without a reply uttered a scream and rushed into the house. They continued for some distance further at this low altitude and came across a farmer, who told them that they were near Fort Washington, Pennsylvania. And then they ascended again and traveled all night at about 5,000 feet. At sunrise this morning they found themselves over Philadelphia. Mr. Erbslöh wanted a current that would take them Northward to New York, or possibly to Massachusetts. Over the city Philadelphia they went up and down from an attitude of 300 feet to 10,000 feet, which was the highest they were during the trip.” The temperature measured 3 degrees above zero.

By the time the Pommern landed at Asbury Park, New Jersey, on October 23, the intrepid pilots had set a new world record, and traveled twice as far as the competitors had done the previous year in France. At just about 40 hours, it was the longest balloon flight ever, and Clayton was a hero. Returning to Canton was easy — it was the town and the people that he loved. From his amazing vantage point he brought stories that mesmerized the young people and adults in the community. He fondly described the views: “The earth looked like a garden, and cars in fog resembled submarines.”

“There was no provision for sleep, but we ate our three regular meals in the air just as if we had been on the ground,” Clayton told the audience. “There was no dressing for breakfast, or dinner, except for exchange of our shoes for slippers, and to remove wraps, as the temperature demanded. For food we carried such provisions as rolls, muttonchops, mutton stew, fried chicken, eggs, crackers, and sausage. For drinks we carried some dozen or so bottles of Apollinaris water, a bottle of coffee, a bottle of tea, and two or three bottles of wine.”

Always, credit was given to the science that was being recorded at the Blue Hill Observatory. And taking nothing to chance, Clayton conducted studies in St. Louis as well. “The observatory had been at work for two or three years in sending out exploring balloons with recording instruments from St. Louis for the purpose of making a scientific study of atmospheric conditions in the United States, up to as great a height as possible,” he explained. “Such explorations have been carried on intervals since the World’s Fair and the conditions of temperature and wind movements ascertained up to heights of 10 and 11 miles. This kind of exploration had been previously made for several years at the [Blue Hills] Observatory by means of kites, but the use of balloons is prohibited [in Canton] because the prevailing upper winds are toward the sea, and would in this way carry all the balloons out to the Atlantic.”

In later life, Clayton went to Argentina to study weather and again used kites for recordings. It was here that he pursued research on a system of weather forecasting based on solar heat and began corresponding with the American astrophysicist Charles Greeley Abbot, with whom he would become a lifelong friend. Returning to America, Clayton worked for the Smithsonian Institution researching the effect of solar variation on world weather patterns.

Clayton’s home in Canton was at 1410 Washington Street, and he died there in 1946 at age 85. Associations with our town were strong as he served as president of the local historical society and the church board of the First Unitarian Parish.

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=20349