True Tales: A Hero’s Service

By George T. ComeauEditor’s note: The following is the first in a two-part series on WWI hero Helen Homans. Click here to read part two.

On July 4, 1926, a small parade formed at the corner of Neponset and Washington streets. The men of the Edward J. Beatty Post gathered to march to Canton High School in order to dedicate a monument to the 13 men and one woman who died in the “Great War.”

The war monument in Canton Center, now relocated to Canton Corner Cemetery at Veterans Park (Courtesy of the Canton Historical Society)

During the dedication, Selectman Leo Galligan greeted the crowd that encircled the granite and bronze monument. In accepting the monument, Galligan pronounced that this was the “testimonial to our brave sons and illustrious daughter, who gave their lives that the world might be a better place to live in. I trust that the folks who pass here each day will utter a silent prayer for those who made the supreme sacrifice.”

As a lone bugler played Taps and the Norwood Elks played the Star Spangled Banner, the crowd began to silently disperse. One woman stayed behind, and traced her fingers across the ninth name cast in bronze. A simple memory flooded back to Edith Wolcott Parkman — that of her dear friend Helen, who, had she lived past the war, would have become her sister-in-law. There was a single June day in France in 1917, when Helen flew down a dusty road in Pont-Audemer on her bicycle — riding to greet the immigrant “rappatries” sent by the Germans to France by way of Switzerland. Helen greeted the children with biscuits and chocolates and supplied the needy with clothes, shoes and other necessities. Her father’s wealth was well spent from her purse during the war. Helen Homans, a nurse from Canton, was destined to become a war hero.

The truth of the matter is that death knows no appointments with the future and Helen Homans died valiantly in World War I, becoming the only woman from Canton to fall in the line of duty.

Homans was born in 1884 to one of Boston’s most prominent families and could trace her lineage back to the American Revolutionary War. Her mother was Helen Perkins Homans and her father was Dr. John Homans. In the Homans’ family you were either a lawyer or a doctor, with great reverence and preference given to those in the family that followed a medical career.

The first John Homans in this country had come from Ramsgate, Kent, England. Homans served as a vessel master plying trade between London and Boston. Establishing roots in Dorchester, the second generation was marked by a Harvard-trained surgeon, Dr. John Homans. Graduating in 1772, it was Dr. Homans who tended wounds on the evening of the battle of Bunker Hill, subsequently serving through the Revolution as surgeon and adjutant of a dragoon regiment of the Massachusetts Continental Line. Thereafter, if your name was John Homans you were likely to be involved in medicine.

Successive generations were all equally equipped for Brahmin stature. Helen’s father was a surgeon with the Union Army and Navy during the Civil War, serving on the staff of Major-General Sheridan. After the war, Dr. Homans became a medical pioneer at Massachusetts GeneralHospital.

Helen’s older brother, John, the fourth “John” to practice medicine, wrote the Textbook of Surgery, a seminal text on the subject that was used in more than 65 medical schools with over six editions in print by 1945. In 1907, John Homans married Abigail Adams, a direct descendant of John Adams and John Quincy Adams. One writer observed in 1918 that “with the exception of a few years at the beginning of the 19th century, marked by the interval between the death of one ancestor and the maturity of his son, there has been a John Homans practicing medicine in Boston since 1775.”

With wealth came trappings. Growing up on the slope of Beacon Hill, Helen’s second floor parlor looked out over the Charles River. In the heat of summer, the family would retreat to their spacious country estate in Canton at Ponkapoag. The young girl was fond of the fields and streams around her second home, and many townspeople recalled the charming girl who adopted Canton as much as Canton adopted her. Helen bred Russian Wolfhounds at the country house in Ponkapoag and spent time with the Hemenway and Bradley families, who had extensive land holdings around the Blue Hills.

Not very much is known of Helen’s early life, except that she attended Miss Winsor’s school. There is a reference to the fact that “she lived in France for a number of months at one time and grown to love the country.” In the shadow of her brothers, Helen had a deep desire to follow a path in medicine.

In 1912, Helen became connected with the Board of Visiting Ladies at Mass. General, volunteering her time within the social services department. Spending time with tuberculosis patients was one of her duties and she excelled in care and compassion. Studying at Radcliffe from 1908-1913 brought her in close contact with the Harvard doctors that would form pivotal contacts in Helen’s role in World War I.

The eminent Harvard sociologist George Caspar Homans observed of his family, “If ancestors are both famous and morally noble … they may challenge their descendants to a noble emulation, inspiring them to achievements they would not otherwise undertaken.” Helen was bound for a noble undertaking.

In 1915, at age 31, Helen watched war break out in what was described as “a brutal attack made by Germany,” such that “all civilization was imperiled.” The United States was not yet in the war, but sympathizers of the British and French sought medical aid and HarvardMedicalSchool answered the call. Homans was among the first women to travel to France to answer the call of duty. Writing in a biography on Helen’s life was Edith Parkman, who said, “Service, human endeavor on its highest plane, was the one directing purpose of Helen Homans’ life. In her eyes, not personal attainment, but contribution to the welfare and happiness of others was the object of existence.”

With a unit of doctors and nurses, Helen set sail for France in March. Upon landing in France, she fell ill for the entire month, yet in April was strong enough to travel to Yvetot, Normandy to join Hôpital de L’Alliance No. 41 bis where she was assigned as a “probationer.”

Writing home, Helen’s letters were filled with her fascinations of the world around her. In one letter she writes of the romantic nature of the “arrival at night in front of the dark group of buildings. A door in the wall clicks open and she is in the courtyard of the monastery, the air filled with the scent of lilacs, and the statue of St. Joseph holding the child looking benignly down at her in the darkness. She enters a little door at the opposite end on the court and steels upstairs past a wonderful old oak refectory to get a glimpse of the monastic dormitories, now transformed into modern whitewashed wards, and filled with long rows of wounded men, their forms just visible by the faint rays of the nurses’ lamps.”

And while the stories she sent home held certain romantic elements, the fact is the conditions were extreme for the doctors and nurses oversees. The cost of this war was enormous and the deaths were agonizingly slow, whether from gas attacks, gangrene or from massive amputations. Disease was everywhere, and the nurses bore the brunt of the work within the hospitals and wards.

By the middle of September 1915, Helen returned to Boston. After seven months oversees the quiet of life at home made “settling down practically impossible for those that had been working in Europe.” After four months, Helen found adjustment a fleeting wish and she returned to France in early 1916. For ten consecutive months, she never missed a single day or hour of duty. A day’s work consisted of “merest drudgery, down on one’s knees scrubbing locker tables, up on stepladders washing down whitewashed walls, cleaning mackintosh sheets until one’s hands smarted with disinfectant.” Edith Parkman wrote that for Helen, “the joy of serving these French soldiers, who every day were going to their death simply and unquestionably, was sufficient reward.”

By autumn, Edith, along with a second friend, Katharine McLennan, joined Helen at Yvetot and the three friends were inseparable. By January 1917 these three women set out together to a military hospital in Chatelguyon, “hoping they might alleviate unspeakable conditions depicted by an English nurse.” It is likely that the three drove themselves, as women figured prominently as drivers in the war. The conditions at the hospital were described as “horror.” Helen, in describing her experiences afterward, told of an Arab patient who jumped out of a window preferring death to his sufferings in the hospital.

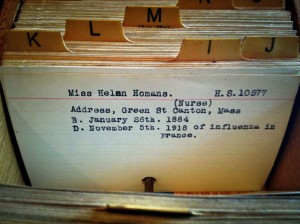

The soldiers and sailors registration card maintained by the town of Canton for Helen Homans (Courtesy of the Canton Historical Society)

Within a few weeks the trio had relocated to Hôpital Auxiliare 109, in Pont-Audemer, Normandy. The hospital, a former seminary, was located on a small hill overlooking the town and surrounded by beautiful gardens. Now a full-fledged nurse, Helen took control of her ward and at her own expense ordered gay colored quilts for the beds and adorned the windowsills with pots overflowing with flowers. Anything to bring cheer to the patients was the order of the day. Helen was an extraordinary nurse, “delighting to indulge her patients in every possible way.” With so many men dying around her, she was an angel that mercifully held their hand as they slipped into the next world.

As Edith Wolcott Parkman left the dedication of Canton’s war dead, the words of Daniel J. Flood’s speech filled her mind: “They made the supreme sacrifice and dedicated their all on the ladder of freedom and liberty. It is not for you or I to embellish their lives, they themselves have done that in the lives they lived and in the way they died.”

The first two years of life in France for our young Canton woman were merely a preamble to what would come next, the task of heading to the front lines of the war at the point when the war would become the bloodiest and most dangerous.

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=20601