True Tales: Helen Homans ~ A Hero’s Death

By George T. ComeauEditor’s note: The following is the second in a two-part series on WWI hero Helen Homans. Click here to read part one.

On her coffin is engraved “MORTE POUR LA FRANCE.” Her medical colleagues had fought to keep her alive, and she herself had struggled valiantly. In the end, it was said, “She had given all her strength to save others.”

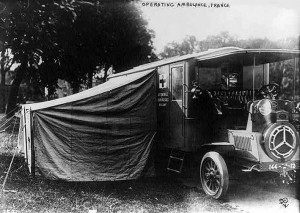

An auto-chir typical of the one that Helen Homans would have worked with in France (Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, George Grantham Bain Collection)

At the Canton Historical Society is a blue wool cloak with a scarlet red lining. This is the cloak worn by Helen Homans in France. Hailing from one of Boston’s most eminent physicians, it was her destiny to find a way to make her life around medicine. After two years in war-torn France, Homans had been trained with solid nerves coupled with the compassion of a saint. A heroic ancestry flowed through her veins as she made her way to the front lines of the war in Europe in October 1918.

After working as an “American nurse,” Homans had the opportunity to join the prestigious Société de Secours aux Blessés Militaires (SSBM), a branch of the French Red Cross, which was an extremely high honor for her. The society had been founded in 1864 upon the principle of providing relief for injured military. On the front lines, the SSBM implemented the use of “surgical ambulances.”

The French had pioneered the use of “rolling hospitals” known as Auto-Chirs. Two Renault trucks served as the sterilizing and x-ray cars. A boiler mounted at the rear of the sterilizing car supplied steam for autoclaves and a sterilizer for boiling instruments. In essence, these were mobile hospitals and came fully supplied with 13 tents complete with canvas corridors, along with extra tents for kitchens and living quarters. To complete the setup, 200 folding iron beds and laboratory equipment made this moveable hospital the most advanced front-line care center in the war.

Homans, accompanied by her two stalwart friends, Edith Parkman and Katharine McLennan, were assigned to H.O.E. 18, S.P. 181, the evacuation hospital at Vasseny. Their main assignment was to Auto-Chir 21, Ambulance Automobile Chirurgicale, one of the mobile hospitals attached to the French Army. On a rainy October morning through a steady downpour, the three friends left under the cover of darkness for the front line. The scene was well described by Edith Parkman: “Shell-ridden Soissons, the little French villages demolished beyond recognition, the countryside now a tangle of trenches and rusty barbed wire, the aeroplanes circling overhead, and finally Hôpital 18.”

As it would turn out, the three nurses were assigned to the largest and best-equipped hospital in the French Army. Composed of wooden barracks accommodating 4,000 patients, it was situated on the Chemin des Dames front, five miles behind the front line. From the grounds of the hospital, Homans could see shells bursting in the trenches. She had arrived in hell.

From the hill overlooking the hospital, Homans could see the Fort de la Malmaison in German hands — smoke filling the skies, her mind wandering to Great Blue Hill so far away and a lifetime ago. In the valley, the “flash of shells as they left the guns disclosed the French artillery emplacements.” As she watched, one of the French lines hit by an enemy plane, crumpled up and burst into flames. The roar of artillery burned through the night, and on the day of the attack, October 22, the objective was taken. The toll was unending; 900 wounded men flooded in and for two weeks Homans had no idea “what she was doing or what people said to her.”

Unimaginable times tested Homans and her fellow nurses as they worked for 40 hours at a stretch — at night without any light to aid them — in order to maintain the cover of darkness.

In one particularly touching case, a 19-year-old boy came into Homans’ ward with a bullet through his spinal cord, paralyzing the boy and ensuring a certain death within weeks. Homans and McLennan decided that he should not die alone, and for ten days they took turns sitting with him, feeding him, and watching him through the ordeal. The sad word came a few days after Homans had left from the front: “The small boy died soon after lunch,” wrote a French nurse.

On March 10, 1918, Homans returned home to Boston and Canton one last time. After three months’ holiday, she sailed for France in July. Rejoining the Auto-Chir No. 21, now established as the L’ Hôpital de l’Armee 65 at Pontoise, this would be Helen’s last post.

Throughout the summer the final offensives of the war pushed in earnest and the casualties rose. From July through October the allied offensive brought a stream of ambulances into the hospital to the former cavalry barracks outside of the small town. More than 1,500 beds filled with untransportable wounded as convoys of the maimed arrived in barges along the Oise River. Literally, Homans was surrounded by the dead and dying and in the dark the groans of the men caused her to wonder, “What victory was worth so much suffering?”

Edith Parkman Homans married Helen Homans’ brother after the war and wrote the Helen Homans biography. (Courtesy of James Homans)

And here is how our hero died. The letters written by Parkman tell the story, which begins on October 29, 1918. “Dear Mrs. Homans: As Helen isn’t feeling very fit to-day and she feels you might worry, not hearing from her, I am writing instead. She is unfortunately ill with this horrid grippe which is raging everywhere and she has been pretty uncomfortable these last six days.” Homans had come down with influenza and her death was pretty certain, although the letters to the family convey certain calmness.

A letter to Parkman’s mother was not as guarded, however. “By the time you get this letter it will be long over happily or otherwise. No one gives us much hope it will be anything but the latter … last night she said she was in heaven … she told me she was dying … she is delirious and thinks Katherine and I are trying to kill her … she is breathing with half a lung.” The letter goes on to say that “perhaps God will spare her; how I pray for it.” During the delirium, Homans kept saying, “She must go back to Ponkapoag — that she knew the way all right.”

American doctors were called, yet they all arrived at the same prognosis. This angel of mercy would soon give the last full measure of devotion — far from home, yet surrounded by friends and two of her brothers who had been summoned from their stations in the war.

A day before she died, the chief physician decorated Homans with the Croix de Guerre with Palm, and the bedside scene was described as most touching and wonderful. “With the armies since the twenty-ninth of February, 1916 she has been noted for her absolute devotion to duty, particularly in the Evacuation Hospitals at Courlandon and Vesseny in the bombarded zone and in an Auxiliary Hospital of the Army where she has contracted in caring for the sick and wounded soldiers a contagious disease which places her life in danger. Given at Great Headquarters by the General, Comander-in-Chief, Petain.”

As the cross was pinned on Homans, “her face suddenly lighted up with the most beautiful smile … from that time it seemed as if there was some hope.” It was not to be, however, and on Tuesday, November 6, 1918, at 5 p.m., Helen Homans — a war hero — passed from this life. She died a most glorious death, the culmination of her life laid down for France. On Thursday the little chapel in the village was made beautiful by a mass of flowers. All the nurses lined up on one side, across from Helen’s brothers, Robert and William. Edith wrote that the “sadness [was] partly taken away by the glory of it.” No one could have wished for a more glorious death. She loved her work better than life itself and she died in the completion of it.

One week later, armistice was declared and bells pealed across the world. At the same time, Homans’ casket arrived in Boston, and on December 14 Kings Chapel was adorned with lilies as the American and French flags stood at either side of the chancel. Homans was buried in Milton within the family cemetery plot. After her death, 275 of her friends raised $21,000 to be used as a scholarship in support of nursing. At Kings Chapel, Harvard University and Mass. General Hospital, plaques were cast in her memory. And in Canton, Helen Homans is the ninth name in bronze on our memorial to the fallen of World War I. Please say a prayer for her on Memorial Day.

Special thanks to James Homans, Esq. for his kind assistance.

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=21097