True Tales: Commodore Downes

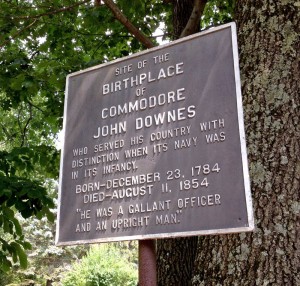

By George T. ComeauOn a snowy December morning in 1784, a few days shy of Christmas, Naomi Downes labored as her husband, Jesse, waited outside for the news of the birth of their child. Naomi pushed and during her last contraction, she uttered to her midwife, “I am ready.” The Downes were not wealthy, and the small house near the corner of what is today Pecunit and Elm streets was modest in nature. In due course, the cry of a baby could be heard through the wintry air, and one of America’s most brilliant and illustrious naval figures was born.

John Downes was born into a world that had recently crafted liberty, a concept that was still weak and needed defending. John’s father was the purser’s steward on board the newly commissioned Constitution. Old Ironsides had an impressive crew, commanded by Captain Silas Talbot, who had supervised construction of the ship in Boston. Launched in 1797, the Constitution’s first duties with the newly formed United States Navy were to provide protection for American merchant shipping during the Quasi-War with France and to defeat the Barbary pirates in the First Barbary War.

Following in his father’s footsteps, John Downes went to work alongside his father as a waiter aboard the ship. It was not long before the industrious nature of the 14-year-old boy was taken note of and rewarded with additional duties. Commodore Talbot observed that the young Downes had uncommon abilities and said to his father, “Downes, I must have that boy.” Soon thereafter, the young man was transferred to the captain’s service, turning the boy’s attentions toward studying and learning all things related to the sea. In 1802, when the Constitution returned from an extended voyage in the West Indies, Downes was offered a midshipman’s warrant, which he ultimately accepted.

In 1803, Downes returned to the sea aboard the frigate New York bound for Tripoli. Reports from the period single out the distinguished service of the young midshipman. Things were heating up in the battles with the Barbary pirates. The small Moorish kingdoms on the Barbary Coast of North Africa were attacking American ships, killing and imprisoning crewmen and stealing cargo, while demanding high monetary tribute. During this period of American naval history, Downes served aboard the Congress, Constitution, and the Spitfire.

In 1807, at age 23, Downes was promoted to the rank of lieutenant and served aboard the newly commissioned warship the Wasp. Tensions had been building within the United States as Thomas Jefferson had imposed an embargo on trade with Great Britain and France during the Napoleonic Wars. The embargo was a response to violations of U.S. neutrality, in which the angry European navies seized American merchantmen and their cargo as contraband of war. The British Royal Navy, in particular, forced thousands of captured American seamen into service on their warships. Downes saw service enforcing the embargo off the coast of Maine, as well as patrols along the Southern Atlantic.

When war broke out in 1812, Downes was in the thick of many successful battles aboard the Essex. Less than 30 years from the end of the War for Independence, the United States found itself once again battling England. This time, however, one of the major theaters was the sea. The Essex was the key player in these battles, and Downes played a courageous role in the war.

In one of the more colorful battles, Lieutenant Downes was dispatched to capture the British ships Georgiana and Poltey. The capture of these vessels was done by hand using rowboats. As it turned out, the seas had calmed and the large ships were powerless to move. Coming alongside, Downes had endured a few misdirected cannon shots; approaching the gangway he ordered the captains to surrender and in doing so captured his first two war prizes. The captain of the Essex was so impressed that he gave Downes his first command.

Once captured, the Georgiana armament was increased to six 18-pounders, four swivel guns, and six blunderbusses. Lieutenant Downes commanded 42 men and six volunteers — recently liberated American sailors. Downes was then ordered to proceed from the coastal area to harass the British off James Island in the Galapagos chain.

While nearing the island on the afternoon of May 28, lookouts aboard the Georgiana sighted a mast and sails on the horizon. Downes had found the 270-ton gun-brig privateer Catherine operating as a whaler and accompanied by a 220-ton gun-brig named Rose. Downes ordered his men to give chase and in a common ruse raised the Union Jack to trick the enemy into believing that they were not threatened. Within range, Downes had his men lower a few boats filled with men and captured the two sloops without resistance. The British captains revealed to Downes that they had no idea of the attack until the Americans were already on deck.

Downes had captured 16 guns and 50 sailors were taken prisoner. Yet just as the capture of the Rose and Catherine was completed, a third vessel was spotted — the 270-ton Hector, armed with 11 guns and crewed by 25 men. It was late in the day, but the Georgiana maneuvered to pursue and after several moments of chasing, the sun had gone down before the Americans were in firing range. In the darkness, Downes fired a warning shot across the bow of the Hector and she returned fire with inaccurate broadsides. Downes, then engaged, fully and viciously raked the British ship with broadsides, ripping off the main mast and most of the rigging. Then four more broadsides followed and the Georgiana moved in to board the enemy. As the Americans drew near, the British lowered their colors and surrendered so the boarding took place without further injuries. By the end of the skirmish, two British sailors were killed, six lay seriously wounded, and 75 were captured. There was not a single casualty among Downes’ crew.

The war prizes mounted and so too did Downes’ rank. Downes was promoted to master commandant in 1813, and two years later he commanded the brig Epervier in the squadron employed against Algiers under Stephen Decatur. In May 1817, a naval ball was held here in Canton at Everett’s Hall. All of Canton’s dignitaries attended to give praise to their son and naval hero. By 1818, Commander Downes was sent on a three-year voyage to South America. This tour, however, was unlike any other. Downes transformed his command aboard the U.S.S. Macedonian into a floating bank for privateers.

The men under Downes’ command complained bitterly about their treatment, writing of how they “were forced to eat mealy grain while counting hundreds of thousands of dollars in specie.” Most of the men felt that Downes was doing this for the “good of the captain” and openly complained that the work they were doing was for the captain’s personal enrichment. One midshipman, William Rodgers, resigned from the Navy after this three-year stint, citing that he was not able to “do what I joined this man’s Navy to do. Not being able to serve my country but to simply be serving for the monetary good of Captain Downes.”

It seems that not only did his men dislike him, so too did the local government. During this period of Downes’ career, the Peruvians marked him for assassination. While ashore in Lima, Downes got wind of the very real threat upon his life and donned a monk’s robe as a disguise to slip back to the docks and rejoin his ship.

The U.S. Naval command, however, had no problem with Downes, and in July 1831 he was ordered to hoist his flag aboard the Potomac as commodore of the Pacific Squadron. During his service in the Pacific, it was at Sumatra that Downes punished the enemy the most viciously. In response to the 1831 massacre aboard the American ship Friendship, Downes was sent to punish the people of Quallah Battoo.

On February 7,1832, Downes sent a pre-dawn detachment of 282 Marines and bluejackets with orders to take four Malay forts along the coast. They divided into four parties; the Marines braved showers of javelins, musketry, and at times cannon fire. The sailors and Marines “stood it like brave fellows,” capturing the forts, then setting them and the town ablaze in order to destroy everything of value.

In five hours, the forts were taken, reportedly with all 150 of the defenders, including the local chieftain, fighting to the death. Two days later, Downes bombarded the defenseless village and killed 300 more civilians. Downes was severely criticized for his actions, yet President Andrew Jackson supported him and in doing so sent a strong message to foreign governments. Downes left the area to continue his journey, eventually circumnavigating the globe, stopping at Hawaii and entertaining that nation’s king and queen aboard his vessel on July 23, 1832.

Downes’ career at sea ended May 23, 1834. Returning to Boston, he became the commandant of the Charlestown Navy Yard. He was one of the highest ranking officers in the Navy, with only three officers ranking above him. On Saturday morning, August 12, in his 52nd year of military service at age 69, Downes looked from his window at the Boston Harbor and uttered his final words: “I am ready.” The nation mourned as Downes was buried at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge.

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=21688