Clang, Clang, Clang

By George T. Comeau

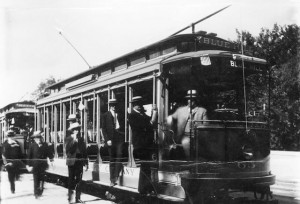

A frequent winter image along the Blue Hill Street Railway in Ponkapoag (Courtesy of the Canton Historical Society)

This story was reprinted in the February 28, 2019 edition of the Canton Citizen.

Canton sounds different — historically speaking. For one thing, no longer can one hear the sound of factory whistles, or a neighbor’s cow, or even the clinking sound of the milkman’s bottles. So much of our daily lives have changed over the course of our town’s history. We cannot quite place a date or time when most sounds ended, except for one. The sound of the trolley bells that once clanged through Canton Center were silenced forever during a snowstorm on February 5 and 6,1920.

The photographs are an anomaly. When we see the Blue Hill Street Trolley cars frozen in time, we cannot but help ask the question: Is this really Canton? It all started in 1899 and the trolley line lived for 21 years. Promoted, constructed and owned by Stone & Webster, the Blue Hill started during the height of the trolley era in New England. The 15-mile line connected Boston with the suburban towns of Milton, Canton, Stoughton, Sharon and Norwood. In particular, it served the fledgling Blue Hills Reservation and was a critical link for businesses and factories along the route.

What made this trolley different than most, and likely led to its downfall, was the fact that this system was built from the suburban towns into the city as opposed to being built as an extension from existing city lines. As a result, the system was plagued with equipment, operations, and financial problems from the start. The Blue Hill Street Railway was never profitable, and near the end of its life, it was the financial ruin for some investors.

It was originally to be named the Stoughton, Canton and Boston Street Railway and was the work of Charles A. Stone and Edwin S. Webster. Stone met his lifelong friend and partner, Webster, while they were studying electrical engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. These two men graduated in 1888 and left an indelible mark on electrical engineering, still visible today.

Electricity was an exciting new field, and cities and towns were building local utilities to meet the large-scale demand of this new innovation. In 1889, Stone and Webster’s parents provided seed money to form a consulting firm, the Massachusetts Electrical Engineering Company, whose first client was a paper mill in Maine in need of a hydroelectric plant for its power. Public utilities became the niche specialty for the firm, and they began managing power stations in 1895, financing them in 1902 through an in-house securities department, and constructing them throughout the firm’s history. By 1912, the firm had 600 consultants housed in an eight-story building, yet Stone and Webster retained adjoining desks and jointly signed their firm’s letters.

The Blue Hill Street Railway, No. 65, at Mattapan Square on August 15, 1903 (Courtesy of the Canton Historical Society)

In Canton, Stone and Webster had little difficulty finding investors for the project. Several notable and wealthy citizens signed on. The initial incorporators were a “who’s who” of Canton’s upper echelon. Names like Forbes, Huntoon, Chapman, French, Sprague, Everett, Endicott and Rogers brought the capital needed to build this ambitious system. The route was originally proposed as “commencing at the terminus of the Brockton Street Railway Company in the town of Stoughton … extending through the towns of Sharon, Canton and Milton … to the line separating Milton from Boston … and the town of Hyde Park. Its length will be fifteen miles.”

Within a few months, nine miles of track were completed, making it possible to get from Stoughton Center along to Cobb Corner, via Central Street, and then up Washington Street to Ponkapoag where Connor’s Wayside Furniture is today. Over time rails were laid down Sherman Street to connect to Canton Junction. Eventually trolleys would run over the Spaulding Street Bridge and down through Jackson Street to Neponset Street and terminate at the bridge over the Neponset River into Norwood.

The building of tracks was only part of the equation. If you drive down Bolivar Street, just after the Town Barn in the distance you can see what many locals refer to as the Chicken Factory. The moniker was earned in 1935 when Furman-Meyers, Inc. began operation of a poultry dressing and packing plant. But before it was destined to handle chickens, this was a state-of-the-art power station running coal-fired turbines for the Blue Hill Railway. Another power vestige is the Kessler Machine Works at the Canton Viaduct, originally a power sub-station. And the small pizza place across from Canton Junction was once a waiting room for the trolley system — relocated to Sherman Street at some point in its history.

In the earliest of days the line was operated in three parts due to the fact that it crossed railroad tracks along the way and the railroad declined to allow crossings. This meant that passengers would board the trolley at Stoughton Square and have to get off two more times and board another waiting trolley just to get to Ponkapoag. Eventually the Massachusetts Railroad Commission allowed the crossings, and by September 1901 most of the system was built. The complete connection through to Mattapan was competed in the summer of 1903.

The trolley never made money for the investors. In fact, it hemorrhaged money consistently throughout the operation. In 1903 the company turned a profit of $84.67 and it likely never was able to pay any dividends to shareholders. Most of the ridership occurred between Memorial Day and Labor Day when thousands would flock from Boston to the Blue Hill Reservation. The local population of Canton at the time was under 5,000 citizens, and most did not travel between the towns served by the trolley system.

Not only did the trolley line lose money, it was also at times a dangerous ride. John Carroll lives on Pleasant Street and his father, also John Carroll, was a conductor on the Blue Hill Street Railway. “My dad used to tell stories of how he would fly down the hills in Milton near the fire station,” said Carroll. Under their own power, the 28-foot cars would gather quite a lot of speed unless checked by the breaking systems. Derailments were common, and descendants of Faustina Estey Shaw Jennison still recall her remarking how she was on that streetcar the day it tipped over by Canton Corner Cemetery. “She said she thought she was going to wind up early at the cemetery in that accident,” recalled one family member.

A snowbound car along the paralyzed line on February 6, 1920. Trolleys never ran after this photo was taken. (Courtesy of the Canton Historical Society)

The worst accident, however, occurred at 9 p.m. on October 10, 1904. A Mattapan-bound trolley was unable to stop due to wet leaves on the rails, slamming head-on into a car heading towards Ponkapaog Hill. The motorman, Frank Smith, was killed and found dead, “tightly wedged between the vestibules of the two cars.” The 30-year-old trainman left five children. James Dugan, an employee of the railway, had his left leg crushed in the accident and amputated above the ankle. In the darkness of the wreckage the motorman, Ed Sheehan, “managed to crawl over” to Dugan. “What is the matter, Jim?” he asked. Dugan said his legs were crushed and he was afraid he was bleeding to death. Sheehan tied the leg with a handkerchief and then fainted beside his comrade, whose life he saved. The seven passengers from Mattapan were badly shaken up, and the lawsuit that ensued cost the trolley company dearly.

In order to build ridership, the company began raffling off small pets to encourage children and their parents to ride. Rabbits, white rats, and “well-bred pigeons” were distributed. One resident remarked that his home was being “turned into a fully equipped menagerie.” The local paper observed, “There are so many pretty animals not needed in the High Street neighborhood, it might be suggested that they be rounded up and tagged for delivery at Blue Hill.” And while ridership was built up, the finances never worked out.

The winter of 1919-1920 spelled the death knell for the system. The company was placed into receivership, and the residents of Canton voted to appropriate $1,500 at the special town meeting in the hopes of saving the company. Mother Nature was not as accommodating. A series of snowstorms forced the system to its knees. The steam generator at the power station failed, and on February 5 an intense nor’easter dumped 17.3 inches of snow on Canton. The local paper described the storm: “Two trains stalled from Thursday night until Saturday morning, one hundred and fifty passengers dependent on Red Cross and citizens for food and shelter. Bread supply exhausted within an hour of each baking. Blue Hill St. Ry. out of coal in midst of storm and may have to wait until line is opened up by thaw.”

The situation was dire; snowdrifts totally covered the trolley cars. “They are still up there, with the snow drifted up to the car roof … under the feet of pedestrians and horses the car line path packed into a solid mass of ice.” The paper went on to consider that “it is presumed that the line will have to be dug out before service could be given, and the lowest estimate of the cost is $2,000. In the present state of the road’s finances … it looks as if the management will have to wait for the next thaw to clear the line.”

The cars stayed right where they froze on that February day. Several months later they were returned to the car house and never ran again — mothballed until a massive fire at Cobb Corner in 1921 destroyed the entire rolling stock and the line became totally abandoned. In time the tracks along Washington Street were torn up and scrapped. There are a few rails rumored to be in a driveway on Sherman Street. There are scrapbooks with tickets, and John Carroll still has his father’s motorman’s badge from a uniform cap.

Pretty much all we have now are the photographs that show this amazingly wonderful yet failed experiment in regional transportation. As the snow falls, it is hard to imagine the frozen trolleys on the hill in Ponkapoag. And, of course, we will never hear the sound of the bell ringing along our main street as we head into history.

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=23740