True Tales: Round & Round the Mulberry Bush

By George T. ComeauA blog on the Internet called “Massachusetts Bass Fishing Spots” extols the virtues of hidden fishing locales around the state. One entry in particular cites the Silk Mill Pond as a covert spot in Canton that might be of interest to anglers.

The source writes of the secluded pond, “It gets pretty deep in the middle so if you want to use a deep running crank bait or let a swim bait sink a little deeper, you should be able to pull out a few. Most of my success has come from working the lily pads against the eastern shore along Old Shepard St. The weeds are pretty thick, though, so you’ll have a tough time getting your bait down to the fish. Instead, fishing the edges of the lily pads will allow you to get the bait to their level and within their range.”

It would seem that bass masters are seeking out the same spot that Virgil and Vernon Messinger sought out, but for very different reasons. The Messinger Brothers built an empire along Silk Mill Pond. Take a drive down Old Shepard Street to see the pond — the mills have long since disappeared. For almost a century the Silk Mill complex was a driving force in our industrial history.

Textile manufacturing in Canton began with James Beaumont’s mill on Walpole Street, built in 1801. It was Beaumont’s belief that he produced the first piece of cotton cloth in America. The claim, however, was not quite true, as it seems cotton cloth was being produced in a small factory in New York as early as 1794. Yet Beaumont’s empire was likely the first large-scale production of the cloth and made a fortune for the enterprising youth.

So it is no surprise that when you look at Canton’s industrial history you will observe amazing progress in both manufacturing and invention of machines that support the cotton, wool, netting, and silk industries. Imagine Canton in the early 1800s: Paul Revere is making copper, Leonard and Kinsley are manufacturing iron, the very parts of the machines needed to support textile mills. And while Canton did not have quite the waterpower of other more famous manufactories, it certainly had enough to support the invention needed for amazing growth.

A map of 1831 lists the industries within the town’s boundaries: “[Two] furnaces for casting canons, bells, and etc., 2 rolling mills & 1 turning mill, 1 large wool factory, capable of manufacturing 600,000 yards per year, 3 cotton factories, 1 thread factory, one satinett factory, 1 wick yarn factory, 1 cutlery factory, 1 candlestick factory & one for farmer’s utensils; 2 steel furnaces, 4 forges, 3 grist mills, 1 saw mill, and 4 machine shops.” The size of the town, coupled with access to the railroad and proximity to Boston, allowed Canton to become the hub of innovation in the early 19th century.

When you consider all that is needed to support a successful venture, both today and 200 years ago, it would seem that we were at the forefront of so many things. To our credit, we boasted strong public schools, great thinkers and doers, and inspiration everywhere. It is against this backdrop that in April 1836 the commonwealth of Massachusetts offered a bounty for the purpose of encouraging the manufacture of silk.

The period between 1825 and 1844 found so many individuals seeking discovery. In Congress, committee after committee was raised to support the silk industry in America. Locally, Governor Levi Lincoln’s focus was on economic development and he was intimately aware of how to promote the textile industry as he himself was connected to the cotton enterprises in Worcester at the time. It was Governor Lincoln who helped fuel the silk industry by offering a bounty of “ten cents a pound for cocoons and a dollar a pound for raw silk.” The first year that the bounty was offered, merely $85 was paid out, signaling warning signs for the silk industry in Massachusetts.

Not heeding the fact that both the trees and the caterpillars could not thrive here, a great business emerged selling mulberry trees. Subsequently, an enormous frenzy called “Morus Multicaulis Mania” swept New England. “Grave doctors of medicine and doctors of divinity, men learned in the law, agriculturalists, mechanics, and merchants, and women as well as men, seemed to be infected with a strange frenzy in regard to this mulberry tree.”

Jonathan Cobb was born in Sharon and was raised in his father’s tavern on the town line between Canton. Attending Milton Academy and later Harvard, Cobb became associated with the law office of James Dunbar and came to know many Canton businessmen. By 1831, Cobb had moved to Dedham and became engaged in the manufacture of silk thread. An early pioneer and advocate for the fledgling silk industry, Governor Lincoln tapped Cobb to prepare the everyday manual on the subject.

Janice Fronko, a textile historian, explains, “The people who had money to invest lost a fortune, and Cobb lost over $50,000. These investors came to learn that the silk worms and trees had to come from other places.” The bombyx mori — the domesticated silkworm — was bred successfully in China and Japan. “As soon as the experiment in New England died out, the wealthy left standing turned to a new business plan to import the raw silk,” said Fronko. “Once here, the silk was turned into thread, dyed and turned out onto spools.”

Things spiraled out of hand when prices for the mulberry trees that once cost $3 per hundred rose to as much as $500 per hundred. Times were rife with speculation, and a great panic ensued, leading, of course, to financial disaster by 1837. The raising and producing of silk in America soon fell to the true entrepreneurs, and in walked Virgil J. Messinger of Canton.

Messinger opened his first silk factory in 1839. Shortly after opening the enterprise, he moved to Needham and made “sewings, gimps and fringes” with Lemuel Cobb (Jonathan’s brother). By 1844 he returned to Canton, and along with his brother, Vernon, erected a newer factory at what was called the Lower Silk Mill Pond. An exhibit in 1847 at Faneuil Hall extolled the amazing new sewing silk “nearly equal to the best imported.” The new modern factory was opened under the name “Messinger & Brother” and would become an empire known throughout the country.

In 1842 the quantity of silk manufactured in Massachusetts was 5,264 pounds; by 1845 Canton alone sent out 5,200 pounds — by far one of the largest outputs in the state. To solve the supply problems, the Messingers imported the silk skeins from China and pulled them into thread and dyed the resulting product.

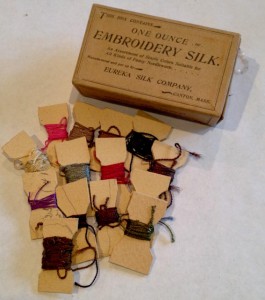

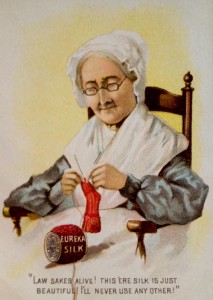

Over the succeeding years the company grew and the mill grew from a modest wooden structure to a fine granite building designed on a grand scale. The business was sold in 1863 to Charles Foster and J.W.C. Seavey, who himself had been with the Messingers since 1853. By 1881, the firm became known as the Eureka Silk Manufacturing Company. Within a year the factory was aglow with the new invention of electricity.

The evolution of Eureka was phenomenal, owing in large part to the patent of the Singer Vibrating Shuttle sewing machine. This lockstitcher was far better than any of the previous machines, and millions of them, perhaps the world’s first really practical sewing machine for domestic use, were produced well into the early 1900s.

As sales of the machine rose, so too did the fortunes of Eureka Silk. Yet, at the same time, competition began to overtake the region, and the rise of the business was offset with a precipitous decline.

In 1894, over 475 workers, mostly women, were employed by Eureka in three large mills. On March 13, 1894, “practically the entire number of girls and young men left their work abruptly at about 7:30 Tuesday morning.” The spoolers and winders of the lower mill marched en masse to the upper mill and gathered more supporters. The two groups marched and eventually more than 375 workers went out on strike. Wages had been cut by ten cents a day and hours had been reduced as “hard times” led to insufficient paychecks.

The papers wrote that the “streets were crowded with a lively and brilliant throng” as a mass meeting was held at Oddfellow’s Hall. Newspaper reporters tried to report of the union meetings, but the “smiling and insistent reporter was as smiling and insistently excluded.” To all in town the front-page story was bolstered by the fact that things were quite “orderly and quiet except for the unusual number of bright dresses on the street and the silent spindles of two out of the three mills.” The mill owners threatened to shutter the mills down, and the girls threatened to go to Brockton for better wages. The state Board of Arbitration intervened and advised the workers to return. The wages had been as high as $6.08 for 58 hours of work, yet the economy of the silk business could no longer meet such generous terms.

In the end, the workers returned to their shuttles without any raise in wages and the mills resumed operation. Mill Number 1 ended production in 1903 and was destroyed by fire the following year. In 1906 Eureka Silk relocated to Connecticut and ceased all operations in Canton.

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=23963