News of epidemic hits home for still-grieving family

By Jay TurnerAmid the recent surge in fatal drug overdoses, the public pronouncement of a “full-blown heroin crisis” by Vermont Governor Peter Shumlin, and the media’s ongoing fascination with the death of Oscar winner Philip Seymour Hoffman, families that have already lost a loved one to addiction are left to quietly ponder how it all went wrong and what, if anything, they can do to help others who are battling the disease.

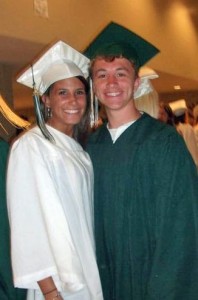

Such is life now for Bob and Diane Breyan, a Canton couple who lost their youngest son, Eric, a year ago this past January. A 2011 Canton High School graduate with a wide circle of friends and a million-dollar smile, Eric had recently completed a 30-day treatment program and was planning a return to college when he was found dead in his bedroom from an apparent heroin overdose at age 19.

“It’s a huge problem,” insisted Diane, with all the urgency of a grieving mother. “There’s got to be something we can do, because right now there’s just too much of it. They’re all dying.”

Diane, it turns out, is far closer to the truth than some may care to acknowledge. For not only has Massachusetts become one of the hot spots for illicit drug use in this country, but deaths by overdose have skyrocketed since 1999 and have become the third leading cause of death in the commonwealth behind only heart disease and cancer, according to a recent report by the Massachusetts Department of Public Health.

As Canton Police Chief Ken Berkowitz told the School Committee back in October following the announcement of a new substance abuse coalition, “Every town and city is going through this. We are no better or worse than anyone else, but I am tired of reading about overdose reports.”

And the biggest culprit continues to be heroin and other opiates, which now account for more treatment center admissions than alcohol statewide, according to a 2012 report by the nonprofit Massachusetts Health Council. The same report states that the Boston Metropolitan Statistical Area, which includes Norfolk County, had the highest rate of emergency department visits involving heroin among 11 major metropolitan areas, topping New York, Chicago and Detroit, among others.

For people like Diane Breyan, such statistics are a stark reminder of something that she learned firsthand a little over a year ago — that heroin addiction has indeed gone mainstream.

“It used to be somebody shooting up in a back alley in a big city, and it’s just not that way anymore,” she said. “Gender doesn’t matter. Status doesn’t matter. Young, old, black, white — I don’t care what it is. None of that matters anymore.”

According to the Mass. Health Council report, “On the south shore, an overdose claims a life every eight days. Records gathered from police, courts, and the medical examiner by the Patriot Ledger shatter stereotypes about who is impacted by drug abuse. The median age on the south shore is 41 and includes homemakers, professionals, and laborers.”

In the case of her son, Diane said there was a time in the not too distant past when he would criticize those who used “hard” drugs like heroin. But then she and Bob started to notice subtle changes in Eric’s behavior, and by the fall of 2012 it had became clear that something was seriously wrong.

“He had gone back to Westfield State that September, and then a few weeks later he called us and said he needed to come home,” Diane recalled. “The desperation in his voice said it all. We had never heard that before.”

When Eric finally did return home, he seemed withdrawn and just not himself, Diane said.

“All of a sudden he wasn’t showering, and Eric had always been very particular about his appearance,” she said. “And then one night in October one of his friend’s parents came over and they told us what was going on. One of his friends actually went up to his room and pulled the needles out. That was a real eye opener.”

Eventually Eric agreed to go to a detox facility, and a few weeks later — on the day before Thanksgiving — he entered another facility on Cape Cod, where the “old” Eric started to resurface, according to his mother.

“At first he was angry, but he settled in and started to get better,” she said. “Then he moved to a [sober house] and he seemed great. He seemed very happy — like my Eric that I always knew.”

Diane said he was still in high spirits when she went to pick him up from the sober house in late January. That was on a Friday. Six days later, Diane was on a business trip in Atlanta when she received the call from her husband.

“I just knew in my heart he was gone,” she said.

***

On January 31, 2014, Diane and Bob Breyan and their eldest son, Michael, held a gathering at their home to mark the one-year anniversary of Eric’s passing. Many of his friends stopped by throughout the night, and some lit candles in his memory that meandered up the stairway to his bedroom.

“For a while, it was my biggest worry that he would be forgotten, but now it is clear that he won’t be,” said Diane, who still talks about Eric every day and remains in close contact with several of his childhood friends, including his “best friend in the world,” Leah Zysman.

Many of them, she said, have been deeply impacted by Eric’s death, and they use his memory to encourage one another to stay on the right path, although she realizes that it is a lot easier said than done.

As for the still-grieving parents, Diane said their mission is now twofold: to preserve the memory of their son and to support others who are struggling with substance abuse.

“Anything Bob and I can do to save even one person is very important to us,” she said.

It’s the reason why they both insisted on mentioning the word “addiction” in the opening line of Eric’s obituary and the reason why Diane recently accompanied someone to a Narcotics Anonymous meeting.

It’s also the reason why she has joined various support groups and forums, and why she regularly connects with addicts online, urging them to “get help,” either by going to a meeting or a treatment facility.

“I feel like my function right now is to try to be supportive to people,” she said. “A lot of families are ashamed to talk about addiction, but if more and more people opened up, I think it would open up the eyes of the police and certainly the community as a whole.”

Beyond her desire to help others, Diane said she also wants to teach people that her son, although far from perfect, was a “regular kid” and a good person at heart — someone who liked baseball and shopping and cared deeply for his family and friends.

“I really want people to remember him for who he was,” she said. “Here’s a kid who loved life, who had a lot of friends, a future. Heroin wasn’t his life.”

Diane and Bob Breyan would like to extend a big thank you and much love to his friends who have been on this journey with them over the past year.

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=24181