True Tales: Skull and Bones Pt. 1

By George T. ComeauThe following is the first in a two-part series on the Burr Lane Burying Ground by local historian George T. Comeau. Click here to read the full text of part two, “A Dog with a Bone.”

Running through the woods on Sunday afternoon in September 1969 were two boys from Sawyer Avenue here in Canton. The crisp early fall day was a welcomed break from the rains that had preceded the week. As the sun cut through the tree-lined paper road known as Burr Lane, the boys took a detour through the old abandoned gravel pit. That was the day that history was unearthed and souls that had been at rest for over 200 years would be disturbed to this very day.

Burr Lane is a small road, more of a dirt driveway off Pleasant Street. You might miss it if you did not know it was there. The name is one of those “place names,” meaning it was named for a person who once lived in that place. In this case, it is named for Seymour Burr. It is an ancient part of Canton and has always been associated with the Ponkapoag Indians.

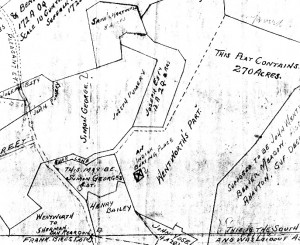

To tell the full story, let’s step back even further. The Praying Indians at Ponkapoag originally owned the land that the boys were playing on that day. The name most closely associated with that part of the village was Simon George. And on that very spot where the boys stood was once a beautiful apple orchard owned by George. In the early colonial days, the Indians were largely forbidden from owning apple trees, and George was the first native to plant an orchard. More particularly, he was the first that was allowed to keep and maintain his apple trees.

The issue in the earliest days of Canton’s history was one of control over the native population. The boundaries of the Ponkapoag Plantation were purposefully cut off from the Neponset River to deprive the Indians of the transportation resource. And since the Indians were very fond of cider, they planted orchards all throughout their land. When the tribe began leasing their land to the English settlers they specifically excepted the orchards from the leases. In 1786 Robert Redman fenced in his orchard of 16 acres and “threatened the Indians with death if they dared to take an apple” from the very trees they had planted. To make matters worse for the natives, Redman also forbade them from gathering cranberries for their own support. It was, however, the cider that was the hardest to bear.

Huntoon’s History of Canton records the great hardship over the loss: “The apples are now coming on, and we set great store by our apples, and hope to have some, not only to eat, but to make cyder.” While many orchards were off limits, Simon George’s orchard was allowed to stay. The seven to 10 acres on Pleasant Street was not only his land, but also his livelihood. In 1732 the Indian commissioners allowed “him and his squaw the liberty to improve, for their own personal benefit, as much of the land that was that year devoted to John Wentworth and William Sherman. On this land lived George and his four children along with his “squaw,” Abigail.

There is an ancient death record that dates to 1739 that tells us that Simon George died in full belief that he was “admitted to that equal sky, His faithful dog should bear him company.” He was buried behind his house in a small graveyard, and his wife and children soon followed him in the afterlife. The land then passed to Jacob Wilbor, who was also buried in the cemetery, and his wife remarried after his death and married Seymour Burr — hence Burr Lane.

Seymour Burr was either born in Africa or here in the colonies. There is conflicting information regarding his birth. Some citations list him as born in Connecticut, possibly of mixed-race parentage; others claim he was born in Guinea, Africa, captured at age 7, and was possibly of royal birth. His enlistment documents list his age as both 20 and 28, which places his birth in either 1754 or 1762. Owned by the brother of Colonel Aaron Burr, who was also named Seymour, he was known only as Seymour until he escaped and used the surname Burr to enlist in the British Army in the early days of the American Revolution. The British had made promises guaranteeing the personal freedom of any black slave who enlisted or escaped to fight against the Continental Army. Burr was quickly captured and forcibly returned to his owner.

Burr, fearing that Seymour would escape again, offered him a different deal: If Seymour would pay his owner the enlistment bounty given to him by the British and serve instead in the Continental Army, he would be given his freedom at the end of his military service. On April 5, 1781, Seymour enlisted in the Connecticut Seventh Regiment, led by Colonel John Brooks. He fought at Bunker Hill and Fort Catskill and suffered through the long winter at Valley Forge.

After his service, Burr was given his promised freedom. In 1805 he married the widow Mary Wilbor, who was one of the Ponkapoag tribe. In marrying her, Burr inherited all of the land that was once Simon George’s, including the burying ground. Burr died February 17, 1837, and was either buried in that small plot behind the house or in an unmarked grave at Canton Corner. Mary Burr died at the age of 101 in 1852 after receiving a yearly pension of $50 since 1838. On her gravestone at Canton Corner reads, “Like the leaves in November, so sure to decay, Have the Indian tribes all passed away.”

Over the course of time the land changed hands many times, and by the early 1900s the property was owned by Eli Withington. It was a wood lot and a gravel pit and Withington was by all accounts a curmudgeon in the classic sense. Carol Shaw Munson recalls her grandfather in a recent conversation: “He was a crabby old guy and very gruff and had a temper … he ended up divorcing his first wife and married Winifred Stone after she lost her first husband. Winifred’s daughter married into the Stockus family and the land changed hands.”

Munson was wistful as she remembers what her grandfather was like. “I met him when I was 11 years old,” she said, “and after the buildup by my mother about his character, I was scared to death.” In time, Munson came to find Withington as a gentle soul and would see him every week after church on Sunday.

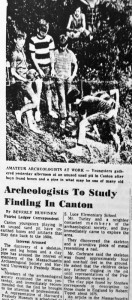

A press clipping from 1969 showing the neighborhood kids at the archeological dig as one child holds a skull

And so, over 130 years later, 12-year-old Stephen Turley and Mark Nannery find themselves playing on the land of Simon George and Seymour Burr and Eli Withington. And it was in Withington’s gravel pit that they began sliding down the steep sandy walls. As boys are prone to do, they examined every root and rock as they happily played. At some point Turley picked up a small clay pipe, a relic from history, and then the chase was on. What else was coming out of the ground that day?

The pipe was only the first part of the story, the key that unlocked the secrets of the burying ground. Taking the pipe home, Stephen told his father, Francis Turley — then principal of the Dean S. Luce School — about a jawbone and leg bones sticking out from the exposed gravel bank. Turley now lives in North Carolina and only vaguely recalls the day he found the pipe. “I saw this little pipe, carved out of bone or ivory … and then I noticed bones,” explained Turley. “My dad knew it was older … he called the experts at the Peabody Museum at Harvard University.” To this day, Turley remembers holding the pipe and bones. At some point, while passing it among his friends, the pipe broke and eventually he gave it to the folks at the Peabody.

In 1969 Canton was a tightknit community, and word among the children in the neighborhood spread quickly. Within 24 hours dozens of kids descended upon their very own backyard archeological site. While the archeologists in Cambridge were mobilizing, the children were digging, and what they were unearthing was amazing and macabre.

By September 17, likely four days after the original discovery, Dina Dincauze arrived on the site. Dincauze led the expedition to Burr Lane and was the lead archeologist. “The children had removed parts of two skeletons,” she recalled, “and members of the Massachusetts Archeological Society had already examined one part of a body in place.” That was where the Peabody archeologists began their investigation.

As dozens of neighborhood children and their parents looked on, the dig began, and piece by piece the remains of Simon George and his family began a long journey into science and history.

And for those who were surprised to find these graves, it was not a secret to our ancestors. Huntoon had written about the cemetery and it even appears on an early map. All the signs were there and this archeological site should have been protected, but what happened next will really shock you.

Look for part two of Burr Lane: Skull & Bones in an upcoming issue of the Canton Citizen.

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=24719