True Tales: Massapoag Meadows

By George T. ComeauThey were called “young hoodlums,” and the newspaper editorial was particularly vicious in the description of these children of Canton. “They are allowed to roam around the village making life almost unbearable for the passer-by on some of our streets during the day and early evening.” It was the heat of that August 1912 that seemed to have brought out the worst in the kids of downtown Canton.

It has been an age-old discussion for this community, that of finding things to occupy the time of our young citizens. Today, the perennial discussion about a youth center is bandied about from time to time, but in fact the discussion has been going on for literally more than 100 years. It is easy to see why things had become so difficult in 1912. The youngsters between the ages of 6 and 14 would literally roam the streets vexing neighbors.

They grow “bolder and bolder day by day, and until some of them are treated at a reform school they will probably grow worse.” The comments in the letters to the editor grew louder and louder. It sounded as if the lunatics were running the asylum. “Almost any afternoon the gang can be seen loitering around the streets, smoking cigarettes and frequently throwing apples and sometimes stones at people passing, and not infrequently at passing automobiles.” In one case, one of Canton’s old and respected citizens was struck in the head with a stone thrown by a young “scapegrace.”

The hoodlumism included “making a racket, pulling the trolley off and stopping the electric cars, singing and clog dancing opposite the Baptist Church on Sundays” — for the times, this was particularly brutish behavior. The problem with youth was largely due to the fact that the immigrant populations in Canton’s factories were burgeoning and hundreds of children were left wholly to their own devices during the summer months.

The elders of the day observed that the parents showed a sad lack of home training and lax enforcement of the law that would allow such actions. Zeroing in on the problem was the fact that most of these rapscallions came from the areas between Washington, Mechanic, and Rockland streets. The police were called several times to break up roving gangs of youth. It was the observation of at least one citizen that the answer was not in law enforcement; rather it was in having the proper space for these children to play.

Canton at the turn of the previous century was the summer home to many wealthy and accomplished families. In particular it was the Cabots that made one of the greatest impacts in Boston society and they summered in Ponkapoag. John Cabot arrived at Salem in 1700. From that point forward, the Cabot family has enjoyed a long tradition of wealth, philanthropy, and talent.

John and his son Joseph were highly successful merchants, trading in rum and slaves and also operating a fleet of privateers. Joseph’s son George Cabot furthered the family fortune, but he is best remembered for his political career — especially his leadership of the Federalist Party.

Over the generations, the Cabots moved from Salem to Beverly to Boston. Intermarriage with other wealthy Boston families produced a socially cohesive aristocracy: the Brahmins. Well-known Brahmins of Cabot descent include Francis Cabot Lowell, Henry Cabot Lodge, and the latter’s grandson Henry Cabot Lodge.

The Cabot family came to Ponkapoag as early as 1865 when the eminent surgeon Dr. Samuel Cabot Jr. purchased the Cherry Hill Tavern as his summer residence. The building still stands in Ponkapaog, moved from its original spot, yet still preserved today. Cabot was one of the most prominent Boston physicians, treating Kit Carson, Grizzly Bear Allen, and Buffalo Bill.

In 1841 Cabot traveled to Yucatán, Mexico. There he and his colleagues learned that the Mayans thought that being cross-eyed was attractive, and therefore did all they could to help there children become so. However, it was during this trip that Dr. Cabot operated on the Mayans and discovered a cure for strabismus — a disorder in which the two eyes do not line up in the same direction.

Cabot also had an illustrious war career. During the Civil War, he was twice sent on special missions. He served as a volunteer surgeon at Camp Winfield Scott near Yorktown, and he returned north with a shipload of those injured at the Battle of Williamsburg. In 1863, Dr. Cabot traveled along the Atlantic seaboard as an inspector of army hospitals. Cabot’s most important accomplishment in medicine was performing (alongside his son) the first two successful ovariotomies in Boston. In 1874, Cabot removed two ovarian cysts containing 24 pounds of fluid from a 24-year-old patient who remarkably survived.

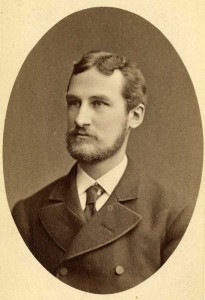

When Cabot died, his son, Arthur Tracy Cabot, inherited property in Canton. The same fields and streams that he played in as a child became his summer home and a favorite escape from an amazing medical career that rivaled his father’s. The younger Cabot contributed greatly to the care and management of tuberculosis, a disease that had a devastating effect on the young.

Described by many people as “cold, austere and even stern,” others would succeed in winning a “rare but electrifying smile.” Cabot, a Harvard man, married Susan Shattuck in 1882, the daughter of another blue-blooded family famous in their own right.

Canton was a special place for the Cabot family. The Packeen Farm on Elm Street was part of Samuel Cabot’s property and passed through marriage into the Lyman family, who, along with the Trustees of Reservations, hold an interest and ownership in much of the original land. Arthur Cabot, when spending time in Canton, was the school physician for more than five years. The School Committee found Cabot to be a “physician of eminence, a public spirited citizen who gave freely of his time and his means to the benefit of the children of the town.”

In 1902, Cabot hired architect Charles Platt to design a Georgian mansion on the property in Ponkapaog. This imposing building was home to the Cabot and Bradley families until 1990, when Eleanor Cabot Bradley died and the 70-acre property was bequeathed to the Trustees of Reservations. The resulting Eleanor Cabot Bradley Reservation is a superb example of the era of country retreats and is open to the public.

Cabot would have read the editorial that condemned the “young hoodlums,” and without any hesitation, within weeks in fact, he gave a large field on Messenger Street “for the use of the boys and girls of Canton as a playground.” To add to the donation, Cabot provided $10,000, “the interest of which is to be used for maintaining and improving this land for games and outdoor sports of all kinds.”

The gift was generous and included four and a half acres of land that was once known as Wentworth’s field. The field was originally built to host Canton’s minor league baseball team. In 1905 the Eliot Athletic Association built a state-of-the-art baseball park near the center of town, “making it convenient to reach by electrics,” reported the Canton Journal, and “the association will wire the grounds for arc and incandescent lights.” The association also secured a building on the grounds that the players — including then 16-year-old Olaf Henriksen (who would join the Boston Red Sox) — used as a dressing room. High-caliber baseball was played there, with teams coming to play due to the convenience of the park via the trolley system to and from outlying towns.

“It is my wish that you should form a corporation to hold and administer the land and fund in the interest of the children of Canton,” wrote Cabot. “In regard to the name of the playground, I think it may be well to call it Massapoag Meadow.” Accordingly, the Canton Playground Association was formed and the first members included Cabot’s brother and sister-in-law, along with Judge Grover, Augustus Hemenway, James A. Leary, and John Richardson Jr. — some of Canton’s wealthiest and influential citizens. The group set immediately to work, grading the south end of the field and building bridges over Massapoag Brook for easier neighborhood access.

The new playground had room enough to host a baseball diamond, football gridiron, basketball and tennis courts, and playground equipment. In addition to the $10,000 fund for investment income, Cabot also made available immediate cash for improvements to open the space for use by 1913.

Thomas Rawding at bat at the Cabot Devoll Playground in 1988 (Photo by David Ciolfi, courtesy of the Canton Historical Society)

At this point Cabot was nearing death — and certainly making plans for his vast fortune. With no children of his own, Cabot saw the children of Canton as part of his legacy in so many ways. In 1911, at age 60, Cabot had undergone surgery for a serious intestinal disease. The pain from recovery was such that he spent most of his last year of life in Canton. By the fall of 1912, Cabot had returned to Boston, where he died in November.

Soon after the death of Cabot, the Boston Herald wrote that he “did a comparatively new thing when his will disclosed that he had given to his native town a playground and money to maintain it. There was originality as well as wisdom in that gift; not only will the constables of that town find less misdemeanors to charge against the active youngsters of the community, but the lads themselves will carry down for many generations, as they enjoy the advantages of that field of wholesome sports, the memory of the kind and wise friend who provided such things.”

The legacy that Dr. Cabot left behind extended well beyond Canton. Large sums of money were left to the Museum of Fine Arts, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard University, as well as several other organizations, which today still use the revenues from the trusts that were established 100 years ago. And here in Canton, the field that he had hoped would be called Massapoag Meadows is now known as the Messenger Street Playground. Children still play there, and it is the only private playground dedicated for public use within the town of Canton.

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=25757