True Tales from Canton’s Past: Drunk & Disorderly

By George T. ComeauThe Rockland Street neighborhood was just that — a neighborhood. Everyone knew everyone else, and in 1912 it was predominantly composed of immigrant families. A look at the census sheet tells the story — names like Casey, Ward, Roache, Fitzgerald, and Sullivan. The occupations further paint the picture: mason, bookkeeper, laundress, assembler, seamstress, and blacksmith. Lots o’ Irish.

There is a long tradition of Irish families coming to Canton around the 1830s and staying here to build amazing lives. St. Mary’s Cemetery is among the earliest Catholic burying grounds in the area with burials beginning in 1847. The Galligans would have been among the earliest of families to come here. We do not know very much about the earliest generation except that Henry Galligan was born in Ireland in 1836 and came here through Rhode Island and settled in Canton around 1860. That was the year that his first daughter was born, and her death certificate indicates she was born in Canton. In 1866 he was an ironworker, likely at the Kinsley Iron Works, and built a family here with his bride, Catherine Boylen, who emigrated here around 1859.

It was a hard life for an immigrant family. Their first child, a daughter, died at 3, another died at age 2, and yet a third died at age 4. The boys seemed to have fared better, and in all the family had 11 children. Henry worked his entire life at the forge and iron works. Dying at age 53, he left behind five sons and three daughters. A hard life ended, and the next generation picked up the torch.

Henry’s fourth son, also named Henry, would be different. A first generation Canton-born Galligan, Henry’s birth certificate in 1871 listed him as Henry Gillinghan, likely owing to the rich brogue of the father reporting his newborn son’s name to the Town Clerk. Henry Jr. attended the public schools for a few years, and by the time he was old enough to work he became a teamster for one of the express companies that shipped goods between Canton and Boston. In 1897, Henry married a beautiful girl who hailed from Newburyport. Elizabeth Durham was the daughter of an English mariner who immigrated to America in 1855 and became a Navy seaman during the Civil War. Elizabeth, known to her friends as Lissie, loved her father and mother dearly. Soon after she married Henry, her parents moved to Canton and were here in 1900.

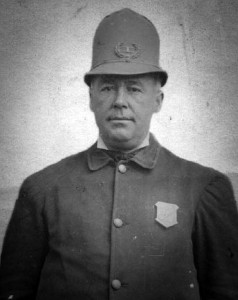

In this immigrant neighborhood on Rockland Street the generations and the languages mixed. Yet the family that stood apart was the Galligans. They rented at 236 Rockland Street and worked to make a better life than their parents. There were a few other “Galligans” living in the neighborhood, but Henry at age 40 was a policeman, and that allowed him to stand out in a town that only had five keepers of the peace. In fact, there were only three full-time police officers in 1912 and two part-time officers who covered special events and the summer through the fall in Ponkapoag and “the Farms” at York Street.

To further distinguish Galligan, he was appointed the chief of police in April 1911 and would serve until March 1913. Although not a particularly long tenure, it was certainly a contentious one, revolving around controversy, allegations, and demon alcohol. While plenty of clichés swirl around the Irish and alcohol, the fact was that in Canton, since the building of the Viaduct, alcohol was a problem that corrupted youth and endangered lives. From the 1860s onward, the temperance movement had a strong foothold among the highbrow Protestant families, and the immigrants wanted nothing to do with outlawing their amber liquids.

From the start of the founding of the police department in 1875 there was one thing that “ruffled the serenity of the local gentry, and that was the sale, use and abuse of liquor.” In the decade that followed, the newspaper was rife with reports and editorials condemning drunkenness. Could Galligan make a difference? He knew his role might be temporary, being one in a line of officers that were “occasionally” appointed chief.

And so Galligan took over from Chief John Plunkett, who was sympathetic to men who were alcoholics and had worked to help their families as they dealt with the devastating disease. Galligan was paid $870 that year and he vowed that he would be different, yet, ironically, alcohol would lead to his downfall as well. In the nine months that began Galligan’s tenure as chief, he arrested 82 people, and 35 of the cases were alcohol related. Moreover, Galligan performed nine major raids and brought 93 cases to court, of which 75 resulted in convictions. Dozens of gallons of liquor were seized as this new sheriff in town upheld the will of the selectmen and made Canton as dry as possible.

The trouble with Galligan started with the trial of Joseph T. Murphy. The two had known each other for at least 12 years. Murphy was only 22 years old and worked as a yardmaster with a steam railway. This gave Murphy easy access to supplies for his side business — delivering alcohol from Boston to Canton. Murphy’s downfall came when he was set up by Galligan through Frank Goff, a member of the Natick Anti-Saloon League. At the turn of the 20th century, members of the Anti-Saloon League set out to “take down” liquor at the source. The moral imperative gave them the sense that if they succeeded in making alcohol illegal, then slums, alcoholism, crime, venereal disease, and a whole host of social ills would disappear.

On June 15, 1912, Goff purchased a pint of whisky from Murphy for 50 cents. Goff found a witness to the sale and together they went to see Galligan to see that justice be done. It would not be all that difficult given that the day prior to the sale, Galligan, under the advice of the selectmen, had made arrangements with the men of the Anti-Saloon League to set the traps in Canton. At the subsequent trial in July, the chief’s testimony was given sufficient weight along with several other witnesses, and Murphy was convicted of four counts and fined $50.

Within two weeks of the initial arrest a feud sprung up between Murphy and Galligan. On June 30 at 12:45 a.m. at the corner of Bolivar and Washington streets, several of Murphy’s friends confronted the chief. Within moments they began claiming that the chief was “intoxicated, staggering and appearing muddled.” Murphy’s pals all corroborated the story that Chief Galligan was stone drunk and reeked of alcohol. A trial was held early in September in Dedham.

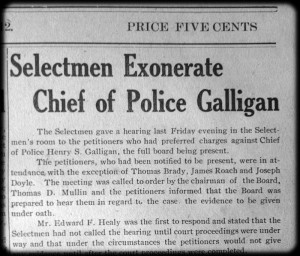

The trial was a sensation. Just days before the selectmen publicly exonerated their chief of police, yet the court saw things differently. On the stand Chief Galligan testified under oath that he had been looking for Murphy in Boston in order to set his bond for the sale of liquor. Arriving back at Canton Junction on the last train, Galligan admitted that he “drank some beer that day, about 7 or 8 glasses. Was not under the influence when arrived at Canton. Had a small bottle of cordial in my pocket that was broken as I left Mattapan Square and could not use my clothes three days on account of the odor.”

Seven or eight of Murphy’s friends all reported that they had seen the chief drunk and accused him on the spot. It would appear that Galligan was enraged and immediately went to Buckley’s Stables and grabbed a horse and team and drove to each selectman’s house and woke them up so they could serve as his witnesses. The prosecutor summed up the chief’s actions: “A man who is drunk persists in declaring he is not drunk, and wishes to prove it, and that was the reason that Galligan went to the selectmen. Any man who is sober would laugh if accused of drunkenness and know he was safe in the fact that he was not drunk. That guilt drove men to declare their soberness when they knew they were drunk.” The defense argued for acquittal on the grounds that “the ones presenting the complaint were an aggregation of undesirables angry with the chief for prosecution against them in the past.” Even the bondsman who testified on Galligan’s behalf was not all that helpful, answering when asked if Galligan was sober “he had been drinking, was highly excited but had perfect control of his mind. There is a twilight state of mellow delight between absolute sobriety and downright drunkenness.”

Galligan was found guilty and fined $15, but he appealed his conviction. The scandalous newspaper account took up an entire page and concluded that “the news was received with astonishment by many while others wore that sort of ‘I told you so’ air. Both sides to this affair have a large following and the case is developing much bitterness.” The damage was done. The selectmen — two of whom had testified in Galligan’s defense — soon dropped their support and not only replaced him as chief but drove him out of the fledgling department. On March 3, 1913, a new chief, John Flood, took the reigns. That year Flood conducted three liquor raids, thus beginning a 22-year career as chief — a position that he held until his death in 1935.

As for Galligan, he bought a house at 145 Rockland Street and became a machinist at a heating manufacturing company, and at the end of his career in 1940 he earned $1,700. Oh, and a bottle of 1940 Glenlivet Scotch Whisky sells today for $21,000 a bottle.

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=26354