True Tales from Canton’s Past: Testing the Bullet

By George T. ComeauOn May 31, 1921, the eyes of the world were on Dedham, Massachusetts, as one of the most famous trials in America was underway. Only a year earlier, a heinous crime had occurred in South Braintree when two men approached a couple of security guards who were delivering the payroll for the Slater and Morrill Shoe Factory. The robbery went bad fast and two guards were murdered — and the hunt was on for the perpetrators.

Three weeks after the murders, on the evening of May 5, 1920, two Italians, Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, fell into a police trap that had been set for a suspect in the Braintree crime. Although originally not under suspicion, both men were carrying guns at the time of their arrest, and when questioned by the authorities, they lied. As a result, they were held and eventually indicted for the crimes. It was to become the most electric and politically charged trial in our history, calling into question the fairness assumption that underlies our judicial system.

At the heart of the case was the very nascent field of ballistics. Four bullets removed from the murdered guards were delivered to “self-educated” experts for both sides. One of the experts for the defense was Augustus Herman Gill. A professor of technical analysis at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Gill was born in Canton in the Tilden House at Pequitside Farm.

Gill, born in 1864, was the only son of Augustus Gill Sr. and Polly Drake. The Gill family traces their ancestry back to Colonel Benjamin Gill, who was born in 1730 in that part of Stoughton that is now Canton. Long lines of Gills are buried in the Canton Corner Cemetery, and the family played an illustrious role in the fight for our nation’s freedom. Through the generations the Gill family played many parts in Canton’s history.

In 1850, Augustus Gill Sr. was persuaded by Martha Howard, the widow of Minister Zachariah Howard, to move into her house on the country estate on Pleasant Street. Mrs. Howard survived her husband by more than 44 years, and in her old age she came to love the company of her cats and the young Gill family. So fond was Gill of Howard (and vice versa) that he named his first-born daughter Martha Howard Gill after the dowager. Against the backdrop of the Tilden House the Gill family grew and prospered. When Howard died in March 1856, it seems that she left the house to Gill. The family continued to live on Pleasant Street, and the 1870 census shows them still at the Tilden House with Augustus Sr. listed as a carpenter and having $1,300 worth of real estate and over $1,800 in personal possessions. At the time the vast property was likely owned by Lydia Ward, whose husband was an American agent for an English banking house. Young Augustus attended Canton High School in 1880 and graduated from MIT in 1884 at the age of 20.

Continuing to live in Canton, the young professor began to set his sights on Europe, and in 1888 he sailed from New York aboard the Red Star Line for Antwerp. Joining Gill were professors Arthur Noyes, F.F. Ballard, and S.P. Mulliken. These were all close friends and men of science who chose to finish their studies abroad. Over the course of two years they visited Brussels, Amsterdam, Delft, and the Hague. The men, thirsty for knowledge, met some of Europe’s finest minds. In the summer of 1888, Gill studied with Adolf von Baeyer, who would later win the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1905. In 1890, Gill received his PhD in chemistry from Leipzig University in Germany. By late September he was back in Canton and again teaching at MIT.

Canton was Gill’s home, and he was very fond of the people and places. He was a member of the Masonic Lodge and president of the Canton High School Association as well as clerk of the First Parish Church. In a letter dated October 17, 1890, Gill writes to his close friend, James Draper, who had moved from Canton to Wyoming to start the Neponset Land and Livestock Company. Gill notes, “It now seems as if I had not been away at all but for the changes in the children and trees.” Upon returning to First Parish he writes, “The church pleases me very much indeed, everything is harmoniously executed, the windows though not elaborate are very pretty and appropriate. The electric lights in the hall are an excellent thing and do away with the ill smelling oil and show of the dresses to good advantage.”

When Gill writes of the ill smelling oil, he is of course referring to oil lamps that burned in the parish hall. And when it came to oil, Gill was the expert. During his tenure at MIT, Gill specialized in oil and gas analysis and the practical testing of alkaloids, asphalt, oils, glues, inks, soap, and wood preservatives. In that same letter to Draper, Gill writes, “I have more responsibility and can see the professors treat me differently from that which they did. I am in charge of a course in Gas Analysis, a new thing here…”

As industry boomed in America in the late 19th century, the use of oils and lubricants became serious business. During this period, analytical methods were being developed, including flash point, specific gravity and friction testing. Fueled by the industrial revolution, the surge of interest in oil led to formalized studies being headed by Gill. Before long, a multitude of papers and books emerged dealing with lubrication, friction devices, and physical properties analysis. One book in particular, published by Gill in 1897, entitled “A Short Handbook on Oil Analysis,” is regarded as the seminal work on the subject.

A professor at MIT for nearly all his career, Gill’s passion for testing led him towards practical applications rather than theoretical pursuits. He is credited as being the first person in the United States (perhaps the world) to offer formal instruction in the analysis of gases and oils. During his tenure at MIT, literally thousands of students attended his courses on the subject. Gill was a founder of the American Society for Testing Materials and in 1906 was made a full professor, subsequently named an emeritus professor in 1934.

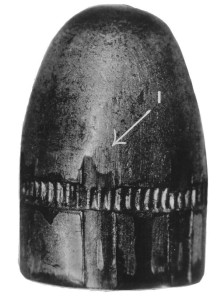

Bullet Number III, allegedly fired from Sacco’s Colt pistol and studied by Augustus Gill (Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court)

In the science behind tests, it was Gill that was brought in by the defense in the Sacco and Vanzetti trial. At the trial itself, Gill, along with another expert, supplied an affidavit that examined enlarged photographs of the bullet and proved the bullet in question could not have been fired through Sacco’s pistol. The trial was sensational and there was a local angle, as Sacco had lived in Stoughton and worked at a shoe factory. Of Sacco, the sales manager was quoted as saying, “A man who is in his garden at 4 o’clock in the morning, and at the factory at 7 o’clock, and in his garden again after supper and until nine and ten at night, carrying water and raising vegetables beyond his own needs which he would bring to me to give to the poor, that man is not a holdup man.” And it would appear that Gill agreed — based on the science of the day.

After Sacco and Vanzetti were found guilty, the nation erupted in protests. For six years the governor of Massachusetts was faced with the question of whether to commute their sentence or consign them to death. In response to public protests that greeted the sentencing, Governor Alvan T. Fuller faced last-minute appeals to grant clemency to Sacco and Vanzetti. On May 23, 1927, Gill was summoned to the governor’s office to discuss the case with Fuller. The New York Times reported that Gill, upon leaving the governor’s office at noon, “would only say that he had been asked to see the governor and that he had talked in a general way about the fatal bullet and about the gun.”

On June 1, 1927, Governor Fuller appointed an advisory committee of three: President Abbott Lawrence Lowell of Harvard, President Samuel Wesley Stratton of MIT, and Probate Judge Robert Grant. The “Lowell Committee” was tasked with reviewing the trial to determine whether it had been fair. As part of the work of the advisory committee Gill was called upon to witness a new ballistics test. This time, a recently invented comparison microscope allowed a side-by-side analysis of the bullet. On June 3 in Dedham, with Gill acting as a witness, a bullet from Sacco’s revolver was fired into cotton wool and then placed beside the murder bullet.

“The outcome was unequivocal — the murder bullet had been fired from Sacco’s Colt automatic.” Gill changed his initial innocence stance and agreed. The new findings were furnished to the governor and the Lowell Committee.

On August 15, 1927, a bomb exploded at the home of one of the Dedham jurors. On Sunday, August 21, more than 20,000 protesters assembled on Boston Common. The next night, at midnight, Sacco walked quietly to the electric chair, then shouted “Farewell, mother.” Vanzetti, in his final moments, read a statement proclaiming his innocence, and said, “I wish to forgive some people for what they are now doing to me.”

Gill continued his illustrious career and moved from Canton to Belmont sometime after 1910, dying there in 1936. Today, quite literally, the “Oscar of Oil Analysis Programs” is named the Augustus H. Gill Award. Each year, industry professionals aware of the importance of oil analysis in the greater picture of machine reliability gather to celebrate the man from Canton regarded as the father of oil analysis. Few people know of his connection to one of the most famous trials in the country.

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=28365