True Tales: The Paper Chase

By George T. ComeauIt is the glue, the paper, the ink that all decompose over time and produce that smell that is all too familiar to historians — old books. And stacked deep on the shelves of the Canton Historical Society are three enormous and ancient volumes of records that carry the smell of both time and history. These are the Ancient Stoughton Records.

First of all, the three volumes are bound in leather and each contains close to 1,500 pages of pasted notes, orders, tax summations, grievances, and land records. Some pages have a single sheet pasted onto the leaf, while others have over 15 or 20 individual entries. Most are handwritten, while others are printed orders from King George. What these documents amount to is well over 10,000 small snapshots of the historical goings and comings of the place we now call Canton. The records start in the mid 1600s and travel through 1813.

The covers are dusty and timeworn. Inside, as the books are carefully opened, the brittle paper ruffles and the scent rises. It starts as something faintly musty, but as the nose grows accustomed, new smells emerge — vanilla, smoke, and grass. Scientists know that compounds in the paper and ink that are breaking down cause the smell. There are literally hundreds of volatile organic compounds released into the air from the books. In scientific terms, it has been described thusly, “A combination of grassy notes with a tang of acids and a hint of vanilla over an underlying mustiness, this unmistakable smell is as much a part of the book as its contents.”

And of the preserved contents, they form a treasure trove, which many towns and cities have long since lost. It is interesting to note that so much of the earliest paper records have been lost to rain or fire, yet here we have been most fortunate to have found survivors of a rare historical collection. It is known that Daniel Thomas Vose Huntoon, Canton’s first historian, largely assembled these three “scrapbooks.” Inside the first volume is an Act from the Great and General Court dated 1851 that is entitled “An Act for the better Preservation of Municipal and other records.” This stands as the call of duty to seek out and “have all books of public record or registry well and strongly bound.”

Great concern had arisen over the loss of records of the “ancient proprietors of townships,” owing to the fact that paper was becoming scarce and old paper in particular was being recycled at an alarming rate. By the 1850s, papermaking in America was reaching a crisis point. America was producing more newspapers than any other country, and its paper consumption was equal to England and France’s combined. According to one 1856 estimate, it would take 6,000 wagons, each carrying two tons of paper, to carry all the paper consumed by American newspapers in a single year.

The Massachusetts Historical Society was at the forefront of urging politicians to find ways to preserve the documentary evidence of our earliest history. “The careful preservation of public records and documents presents an object worthy of the attention of an enlightened government,” wrote James Savage, the MHS president. “In the early establishment of our towns, grants were often made by the General Court of the townships themselves, or of other proprietors, whose records were kept apart from the civil records of the town.”

And so in keeping with this, in April 1871 Huntoon set forth accelerating the collection of every ancient scrap of paper and building the historical record. In order to hunt down these documents, Huntoon published an article in a small newspaper entitled The Vestry Bell, published by the Ladies of the First Congregational Parish. “We want to treasure up all the old traditions from the time of the Indians to the present day. We should like, above all things, to rummage in forsaken attics, to ransack those moldering papers, which the good wife has declared time and time again she will sell to the ragman. We have reason to believe that bushels of this old stuff are yearly given to the flames, and we desire to save it, and that immediately; for if we of the present generation allow these precious memorials of the past to be lost, no industry, no wealth can supply the deficiency.”

The resulting collection is nothing short of amazing. The very first page of Volume One contains a document dated 1649, which is copy of an indenture from 1636 and signed with the mark of Chief Kitchamakin, the brother of Chickatawbut. This is the land sold to Richard Collicott of Dorchester. In iron gall ink the cursive text melts into the paper, at times becoming blurry. “All that tract beyond the Mill within ye bounds of Dorchester for them and their heirs for ever — only reserving for my own use and for my men forty acres where I like best & in case I & they leave it the same alsoe to belong untoe Dorchester, giving some consideration for the paines Bestowed upon it.”

This piece of paper started it all, and it is an uncommon artifact dating to more than 367 years of our place here on this land. The following few pages are more of the same, land deeds that built Dorchester in that part that is now Canton. The marks of Ahauton and Momentaug, along with Wampatuck are preserved for all to know that this land we now inhabit was once the tribal place of the Massachusetts Indian Tribe.

There are tantalizing clues to an extremely early iron mill referenced in the deed of Captain Isaac Ryol (Royall) in which he buys an iron-smelting mill called “London New” from Ebenezer Maudsley. By 1727, Maudsley is operating a gristmill on the land and river at Pacumit, now the land at the Revere Copper Mill. Page after page of records brings the reader deeper into the history and people of this place that in much of Volume One is simply known as the Province of the Massachusetts Bay.

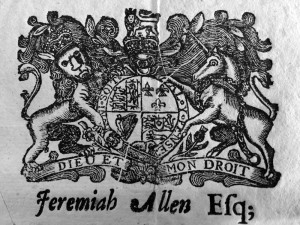

Many of the ancient documents bear the Provincial Seal of Massachusetts and that of the Treasurer and Receiver General for His Majesty’s said province.

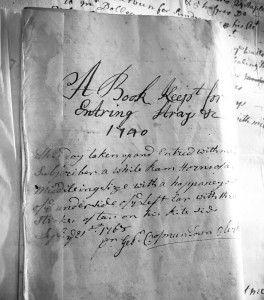

The pages contain detailed land grants, petitions for the laying out or discontinuing of roads, records of the church, and notations of births and deaths. There are wonderful oddities too. Take for instance a small booklet entitled “A Book Kept for the Entering of Strays — 1740.” Inside, over a period of 27 years, the various town clerks record stray animals found by local inhabitants. The history of our town flows easily as we randomly select a typical entry, which reads, “December 1st 1740, Taken up and strayed by Dr. Ralph Pope of Stoughton; a darke gray (or black roan horse) having no artificial mark. Supposed to be about twelve years old.”

So what do we know about Ralph Pope, and is there relevance in these ancient tomes? It turns out that Ralph Pope was a physician who purchased 24 acres of land on what is now Spring Lane — then known as Dunbar Lane. Pope shows up in the town tax records in 1731. That same year he and his wife, Rebecca, were admitted to the church. The family were “constant worshipers” according to tradition, and would make their way to the meetinghouse on horseback each week. The meetinghouse was located in what is now Canton Corner Cemetery, and on July 18, 1731, Pope and his wife were in the meetinghouse to celebrate the baptism of their daughter, also named Rebecca. We also know that Pope brought along a black slave named Scipio, which he also had baptized. Records suggest that Pope was the owner of one of 11 slaves listed in town in 1734. While not a tremendous amount of information is known about slavery in what is now Canton, we do know that in 1748, Reverend Jedidiah Adams married Scipio to Sarah-Mary Slocum, an Indian.

And for every piece of paper that tells a story or fills in a piece of genealogy, there remain hundreds if not thousands of mysteries and riddles. An entry on April 10, 1762 reads, “By virtue of this warrant, I have warned the within named Isaiah Faxson and his wife and three children to depart this town within fourteen days after warning.” This small note, written 253 years ago, leaves a few further clues. We know that the selectmen wanted Faxson to depart and was warned out. This was a common practice to pressure “outsiders” who were considered undesirable to settle elsewhere. Faxson was from Braintree and was living at the house of James Smith. In the books there are hundreds of “warning out” notices and the potential for even more history to uncover.

These early records are about to become the subject of the next chapter in Canton’s preservation efforts. The Canton Public Library and the Canton Historical Society have applied for a grant from the Community Preservation Act to begin the process of creating a plan to preserve and digitize these and hundreds of other historical public documents. Voters at the annual town meeting will vote a modest sum to allow the documents to be studied by a professional archivist to identify and prioritize preservation needs. The hope is to one day digitize these documents and make them available for researchers around the world. While the work will not capture the smell and feel of these books, it will capture the imaginations of writers and researchers for years to come.

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=28933