The Price of Freedom: For local Army vet, war left lasting scars

By Jay TurnerWhether he realizes it or not, Staff Sergeant Eric Estabrook cuts an intimidating figure.

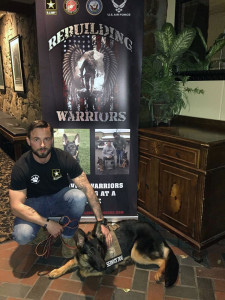

A handsome, physically fit U.S. Army drill sergeant, his demeanor is serious and measured, his eyes cold and piercing. Covered in tattoos and usually accompanied by his two German shepherds — his pet Sadie and his new service dog Freedom — he doesn’t smile much and generally has the look of a man not to be messed with.

And none of it is an act.

On the contrary, Estabrook, who grew up in Canton, is probably a whole lot tougher than he lets on, a true modern-day warrior who thrived on danger and charged headfirst into battle against Afghanistan’s deadliest insurgents.

“I loved [combat],” stated the veteran of two tours matter of factly in a recent tell-all interview. “I don’t think you could ever feel more alive than when you’re so close to death, bullets hissing by you … That was what got us up in the morning — that and blowing [stuff] up.”

A combat engineer by training, Estabrook was part of an elite counter-IED task force that searched for and destroyed improvised explosives. He completed hundreds of dangerous missions during his 21 months in Afghanistan and was so good in this role that he fast-tracked to promotion and was named squad leader for his second deployment. He also completed the Army’s prestigious Sapper Leader Course between deployments and was the recipient of the Bronze Star for his actions in Afghanistan.

Yet underneath this tough exterior of his lies an ex-combat soldier with gaping psychological wounds — wounds that for a long time he refused to even acknowledge, until he was back home and all alone and the pain eventually became too great to ignore.

“Of my time in the Army, very little of it if at all was spent taking care of my own issues,” he said in retrospect. “Everything was just kind of put on a shelf because I had a responsibility as a leader to take care of my men — because they came first.”

“Nothing really came to light,” he said, “until it was all gone and I was in an apartment in East Boston by myself with nothing to do and no more Army.”

***

In a recent nationwide poll of Afghanistan and Iraq War veterans conducted by the Washington Post and the Kaiser Family Foundation, more than half of all respondents reported feeling “disconnected from civilian life” upon returning home from the war, while nearly a third described their mental and emotional health as “worse” than before they deployed.

Even today, after months of counseling and regular doses of antidepressants and anti-anxiety medication, Estabrook would still put himself squarely in both camps, although at least now he has a diagnosis and a disability rating and support from the Department of Veterans Affairs. At least now he has a plan.

Prior to last summer he had none of those things, and so to numb the pain he turned to alcohol. It started with a few glasses of whiskey a night to take the edge off, but as his anxiety worsened so too did the drinking, until it eventually spiraled into full-blown dependency.

“When I moved to East Boston [in February 2014], I would continuously drink until I passed out on the couch,” recalled Estabrook. “That is when the floodgates opened so to speak.”

Full of despair and depression and wracked by crippling anxiety, his drinking became so severe that he would consume up to 2 liters a day. He stopped eating and he rarely left the house. And when he did manage to fall asleep, the night terrors would begin — a string of three or four “horribly graphic and violent” scenes that would batter him in quick succession, like machine gun fire.

“They were usually some variation of something that actually happened,” said Estabrook. “Like the squad leader on my first deployment got his leg blown off and got sent home, and I would have this one dream where I would be in an ambulance with someone and they would have their leg or arm gone and I would be trying to control the bleeding.

“I also had this dream where I would not be in Afghanistan but I would be in a shootout and I would watch all of the members of my family get shot around me. And I would always wake up when I was about to take on an immense amount of firepower. I would have a sequence of these dreams back to back — enough to really alter your sense of reality and just terrify you.”

Although he never attempted suicide, Estabrook said he thought about it a lot during that six-month period after leaving active duty, what he now refers to as his “rock bottom.” He refused to act on it because he didn’t want to hurt his loved ones, but he said there were times when he would sit there with a loaded gun in hand and “just kind of look at it” and think about pulling the trigger.

“There were days when I would wake up on the floor and slam down whatever I could find and lay there and just cry,” he said. “I was so disappointed in myself and I felt so lost and so alone, and I thought the world would be a better place and everything would be better if I was just gone.”

***

In attempting to get at the root of his pain since returning home from the war, Estabrook reveals stunning contradictions that he is perfectly comfortable with but does not expect a civilian to grasp.

On the one hand, he said, it was the fighting that produced the scars, both visible and invisible.

“I wouldn’t want anybody that I care about to have to go through and witness the things that I have,” he said. “Each time it chips away at you and takes little pieces of who you were.”

At the same time, Estabrook said he would “go back tomorrow” if he could, despite knowing full well the risks involved and the emotional toll it has exacted.

“I felt more comfortable deployed and happier deployed and in combat than I ever have being home because it’s just like you have this extremely tight-knit group of guys and each one is willing to die for one another,” he said. “It’s not even questioned; it’s just implied.”

Of his two deployments, Estabrook said the first one, which lasted from December 2009 to December 2010, is still the hardest to relive. They took several IED strikes, and in a span of three weeks in October his squad lost two men.

One of them was Pfc. Ryane Clark, a 22 year old from Minnesota who was killed instantly during an ambush when the vehicle he was riding in was struck by an RPG at point-blank range.

Twenty-one days later, Spc. Ronnie Pallares, 19, from California, was killed during dismounted patrol following a massive IED strike in Ghazni Province. Estabrook, along with two other men, carried Pallares’ lifeless body to the medevac helicopter.

“I was able to have a moment with him and kind of say goodbye before they took off,” he said. “And then the helicopter took off and my whole body just kind of [gave out]. I just lost my legs and fell to the ground.”

After Pallares was killed, Estabrook said the whole squad couldn’t wait to go home.

“We all thought that we were going to be the next ones to die,” he said. “We all kind of knew that each day could be our last. But we still went out on missions and did what we had to do.”

When they did finally return for their second deployment in early 2013, Estabrook, by then a staff sergeant and a squad leader, had resolved to do things differently this time. He utilized a unique ground alignment, consisting of an inside search team, a self-sustained fighting force on the outside, and an over-watch sniper team.

“I put my career on the line,” he said, “I put myself on the line to make sure I had control of what was going on on the ground. And it didn’t matter what your rank was or who you were, you had to listen to what I said and I was going to bring everybody home safe.”

Estabrook said his second deployment, which lasted nine months and centered on Logar Province in the eastern part of the country, consisted of less IED finds and a lot more engagements while dismounted on the ground.

“It was very kinetic,” he said. “There was a lot of fighting back and forth between us and the Taliban. But we built a reputation for ourselves and we were very successful. My guys were operating in a way that nobody else was doing in Afghanistan, and I’m proud that we didn’t lose a man.”

***

Fourteen months after Estabrook returned home from his second deployment, the U.S. military ceased combat operations in Afghanistan, officially ending America’s longest war. Meanwhile, the Taliban is alive and well — just last month they launched their annual warm-weather offensive, attacking several villages in the north and coming within two miles of the capital of Kunduz Province.

Which begs the question: Was it worth it? For Estabrook, the answer is predictably nuanced yet simple.

“We did kind of stand up an army and a police force that didn’t exist, although there is so much corruption over there,” he said. “But mostly we just fought for each other. The politics behind it don’t mean anything; we were just fighting to stay alive.”

Personally, Estabrook does not regret any of his time in the Army, although he recognizes that the war had a “pretty substantial impact” on himself and his men.

“I think that I sacrificed everything that I possibly could for my country and this is the outcome of it, but I don’t regret it and I don’t resent the military. I mean, I love the military.”

He admits that he is damaged because of it and will probably never be the same, but he hopes to find a “new normal” through therapy and medication and to possibly help other veterans in the future who struggle with readjustment issues.

Along those lines, Estabrook was thrilled to have found Rebuilding Warriors, a California-based nonprofit that provides fully trained service dogs to veterans with physical ailments as well as post-traumatic stress disorder and traumatic brain injury.

In April, Estabrook received Freedom — a beautiful, purebred German shepherd puppy — through Rebuilding Warriors, and in the short time they have had together she has already changed his life.

“As soon as I heard about what they were doing, I wanted to be involved,” he said. “Just the possibility of me doing that for another guy who’s in a situation like me, there’s no greater good than I can think of. That’s how I want to give back.”

Today, Estabrook is 10 months sober and is getting the help he needs through the VA and the Boston Vet Center. He credits his girlfriend, Sarah, for sticking by him at his lowest point and for pushing him to get his life back on track.

“I’d most definitely be dead if it wasn’t for her non-stop dedication and support as well as basically giving up everything to take care of me,” he said.

As for where he goes from here, Estabrook said he is still considering a possible career as a firefighter, but he could also see himself with a “house in Canton, a fenced-in yard with an indoor and outdoor kennel, and training service dogs one or two at a time.”

“That’s my dream job,” he said. “I could do that forever.”

In the meantime, Estabrook plans to continue to seek therapy and treatment for post-traumatic stress and to focus on healing and self-improvement. He remains in the Army reserves, but is currently in the process of seeking a medical retirement and believes it is finally time to “hang the Army thing up.”

“I knew at some point there was going to be a time for me to hang it up,” he said. “I knew that I would reach a point where I couldn’t do it anymore, and that’s where I am at now.

“I’ve given the Army and I’ve given my country enough I think.”

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=29713