True Tales Retold

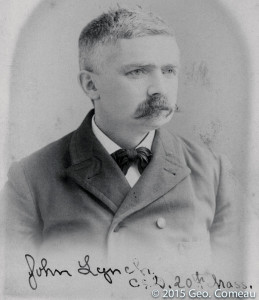

By George T. ComeauThis story originally appeared in the Canton Citizen on June 25, 2015.

There were more than 124 passengers on board the Washington Irving when she set sail from Liverpool, England, in the summer of 1850. The passengers all had mostly one thing in common: They were the Irish that could escape the famine that raged through their native land. The ships that promised new life were called the “famine ships,” and the Washington Irving was the ship that brought thousands of immigrant Irish to Boston.

The keel was laid in 1845 in what is now East Boston at the legendary shipyard of Donald McKay. She was built for speed in the transatlantic trade of passengers, mail and freight services. Launched in September 1845, she began seven years of service, during which time she delivered the dreams of America to those who could escape the horrors of the Gorta Mór — the Great Famine.

On a sweltering day in July, David Lynch and his wife, Honora, walked across the dock in Liverpool. With three children in tow, the scene was awe-inspiring. The Washington Irving was strongly built of the finest materials, with smooth lines and sharp ends. At more than 150 feet long and 30 feet in width, she was built for speed. As is the case now — and certainly was then — time is money. John Lynch, who had just turned 5 years old, held his little sister Nora’s hand as they followed their mother and father up the narrow gangplank.

Stepping aboard the ship, they were met with the smell of salt air and livestock mixed with the sewage that flowed into the dockyard. The ship was filled with animals, and the children could hear the bleating of goats and lowing of cows. As they made their way below deck, the cries of pigs and geese met their ears. This was the same White Diamond Line ship that Patrick Kennedy had sailed on in 1849, leaving his family in southeast Ireland and starting a dynasty in America that would be indelible in our political history. For David Lynch, Boston would hold great promise and a new life in which to prosper.

Arriving in Boston on August 13, 1850, the mostly Irish families began to disperse and find jobs. David Lynch may have stayed in Boston for a time, but by 1855 he settled in Mansfield and took work as a shoemaker. The family grew, and at age 16 John Lynch moved to Canton with two close friends. Lynch had befriended Edward Champney and Charles Ellis, and the three young men set off to work in a boomtown where the work was plentiful.

As early as the 1820s the Irish had come to Canton to work in the factories. The water was clean, the work hard, and the wages allowed for some measure of comfort. The construction of mills and the railroad led to jobs building the Canton Viaduct, and laying the foundation for the Kinsley Iron Works, Revere Copper Works, and the Ames Shovel Shop. Machinists were in great demand, and without any trouble the three men found themselves working in the Kinsley Iron Works as machinists. Within two years of arriving in Canton, the Civil War broke out and John Lynch joined almost 300 other men from Canton in the enlistment drive for soldiers to fight for the Union.

Arriving in Readville on August 9, 1862, Lynch, along with several of his fellow workers, began the journey into what would be battles of life and death among close friends and comrades. John C. Brooks, another Canton man, stood next to Lynch as they both signed forms that would guarantee a $200 bounty for joining up in what would become known as the Harvard Regiment — the 20th Massachusetts Regiment.

Within weeks, Lynch and his fellow friends from Canton were immersed in battle. By December 1862, Lynch was wounded at Fredericksburg, and just six month later he was again wounded at Chancellorsville. Many men died of battle wounds, yet Lynch survived and in July 1863 was fighting at Gettysburg. In the Battle of Gettysburg, Colonel Paul Joseph Revere, grandson of Paul Revere and also from Canton, commanded the 20th Massachusetts. Revere was mortally wounded on July 2 and died on July 4. When Revere fell, Lieutenant Colonel George N. Macy took command until he was wounded on July 3, losing his left hand. Captain Henry L. Abbott then took over the regiment. Lynch fought on and survived a battle in which the 20th brought 301 men to the field, losing 30 of them with another 94 wounded and three who went missing.

On May 6, 1864, Lynch was in the thick of one of the most hideous battles of the war. The Battle of the Wilderness was fought about 15 miles west of Fredericksburg, Virginia, in the area of dense second-growth forest locally known as the Wilderness. It was the first battle of Grant’s Overland Campaign and one of the bloodiest battles of the Civil War. The fighting took place in an area of Virginia where tangled underbrush and trees had grown up in long-abandoned farmland. Close-quarters fighting among the dense woods created high casualties. The battle was a stalemate with heavy casualties on both sides. In the three-day battle the Union racked up over 18,000 casualties. On that day in May, Lynch was fighting alongside Sergeant Robert Blackburn from Canton. Blackburn was a machinist and the two men had been together through most of the war. As a volley tore through the line, bullets shattered Lynch’s right leg and Blackburn died at the side of his friend, the boy from Ireland.

Lynch mustered out on August 1, 1864, and returned to his home in Canton. Soon Brooks and Champney joined him and they began to put the pieces of their life together. All the men who fought in the horrors of the war began to form the Revere Encampment of the Grand Army of the Republic Post. This was their way to gather and recall the sacrifices that were made for the liberty of the United States.

Lynch married Margaret G. Murphy in 1870 and they had at least six children. The children all went through the Canton Public Schools, and their lives brought grandchildren to the long lineage. Settling on Mechanic Street, their backyard was Bolivar Pond, and Lynch decided to make it a public recreation space.

In 1902, Lynch formed the Bolivar Boat Club with six friends. Immediately the largely Irish membership group was successful. By 1906 the club purchased a small building on Sherman Street with the dubious name of Cobweb Hall. Moving the building across town, this became the clubhouse and was beautifully painted and fitted with comfortable chairs and tables to become a gathering space for the members. Large parties and dances were held at Memorial Hall, all with an effort to attract members and raise money to celebrate Bolivar Pond as a natural recreational attraction. Within 10 years the club held carnivals, picnics, and social gatherings and raised significant sums of money to open up the waterways that led to the pond. In fact, the club was responsible for widening more than two miles of tributaries of navigable water to access the beautiful space.

A fleet of canoes and boats were on hand for the members to use, and by 1911 more than 1,800 names filled the guest register, representing more than 27 states and several foreign countries. Lynch never forgot his experience in the Civil War, and the Bolivar Boat Club hosted the 20th Massachusetts Veterans reunion until there were no longer veterans to gather. A gala was held to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the mustering into service, and members and families came from as far away as the Pacific coast to gather on the shores of Bolivar Pond. Lynch would have loved this day as a pinnacle of his dedication to the men of the Civil War.

Sadly, the man who started it all, the boy who had held the hand of his sister on the transatlantic voyage in 1850, had died. On January 7, 1910, the headline read “Mustered Out,” as Lynch the war hero passed away at his home on Mechanic Street. On a blustery Monday morning at Saint John’s Church, a Requiem High Mass was said as the flag-draped casket lay before the altar. There were flowers from every major organization in Canton, yet the most fitting was a floral “anchor” from the Bolivar Boat Club. The pallbearers were a “who’s who” of Irish in Canton. Names like Haverty, Mullin, Whittty, Kennedy, Sheehan, Kelliher, and Cafrey all helped lay this giant to rest. During the war, Lynch had fought with John Brooks. It was Brooks who stood by the side of the casket as it was laid in the ground at St. Mary’s Cemetery.

At Gettysburg there is a large boulder of Roxbury puddingstone, native to Massachusetts and the official stone of the commonwealth. It was brought there to become a monument to the men of the 20th Regiment, many of whom had played on such boulders as they grew up. On July 19, 1909, the summer camp at Bolivar Pond was named “Camp Revere.” The clubhouse was demolished in the late 1970s. Today we need look no further than Bolivar Pond as a reminder of the bravery, dedication, and spirit of one man whose Irish roots ran deep. Today, as we look at Bolivar Pond, let’s not forget John Lynch.

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=29974