True Tales from Canton’s Past: Spare History

By George T. Comeau

You have driven by the small cemetery in Ponkapoag countless times. The weed-choked berm leaves no place to even pull over to take a quick walk through. It sits on a hill sandwiched between two modern subdivisions, and yet it is one of our oldest historic sites and one that tells a story of the New World in America like no other.

It is actually known as the English Burying Ground. It is very small, not more than 70 feet or so on the road, and it runs back to the brow of the hill. At one time you would open an iron gate — now long gone — enter and stand within the enclosure known as the English Churchyard. A description in 1893 captured the scene: “The path, if path there ever was, has long since been choked with weeds; and the rank grass grows in profusion over the graves. The stones are half covered with ivy and creeping vines, and you discern through moss-covered letters the well-known names of those who were once connected with the busy life of the old town.” Over 100 years have passed since the scene was described, yet little has changed to this day.

There are actually two burying grounds here. One portion of this lot has been in use, or, as the old record has it, “improved for a burying ground,” much longer than the rest. The front portion was deeded for the Church of England, where a meetinghouse stood just to the north where Heritage Lane is today. Then the second portion of the cemetery, up on the hill, was owned privately by certain proprietors having no connection with the Church of England. Persons were interred here as early as 1705, and, discounting our Indian cemeteries, it is the oldest place of burial in Canton. When the church parishioners came into possession of the adjoining lot, the two graveyards were merged, and hence here rest side by side patriots and Tories, the division long since dissolved.

Buried together you will find the staunch patriot Captain William Bent, longtime proprietor of the Eagle Inn, reposed in the same yard with Edward Taylor, the notorious and loud-mouthed Tory of Ponkapoag. The good old deacon of Dunbar’s church lies near the warden of the English Church. Here in the northeast corner is a rough stone with no inscription, and not far away is a monument of modern workmanship with this inscription: “Near this spot lie the remains of Samuel Spare and wife who came from Devonshire, England, in 1735, and was the first settler of this name known in New-England. He was active in the church formerly near this lot. He died July 5, 1768, aged 85 years.”

Samuel Spare was born around 1683 and came to the colonies sometime before 1729. Not much is known of Spare’s life in Boston; successful as a trader, in 1739 he was able to purchase 20 acres of land for an extravagant price of 300 pounds. On that property was a house, and Spare moved his wife and their 4-year-old child to the wilderness of what was then Dorchester. The house would have been in the vicinity of Green Lodge Street today. The private road was wide enough for a team of oxen, and the Spare property was the first arable land found after the Ponkapoag Village. The house was torn down in 1856 and was passed over when Green Lodge Street was improved in 1870. There was a fine old orchard of apple trees, and vestiges of the two wells were still remaining as late as the 1890s. To hear of the orchards in this valley recalls how different things were before modern cultivars: “The lady-fingers, the greasy apples, the double apples (nearly a third of them united like Siamese twins), the rattle apples (which when ripe, would rattle their seeds if shaken), the sweet russets and the red russets.” One tree remained into the beginning of the 20th century, being more than 150 years old. Vestiges may still be there today deep in the woods off of Elm Street.

We have one description of Samuel Spare as a “sanguine, earnest man, devout, frugal, thrifty, of such stock that his descendants may reverence his memory, conscious that they have inherited something of his praiseworthy qualities.” As for Spare’s wife, Elizabeth, she was known at the “London Lady” owing to her birthplace. Late in her life, as dementia set in, she would strike a pose before her mirror, adjust her cap, and address her own reflection as if her image was a neighbor and she would remark, “I am coming over to see you, pretty soon.” Anyone who has had a loved one with Alzheimer’s disease will recognize this behavior.

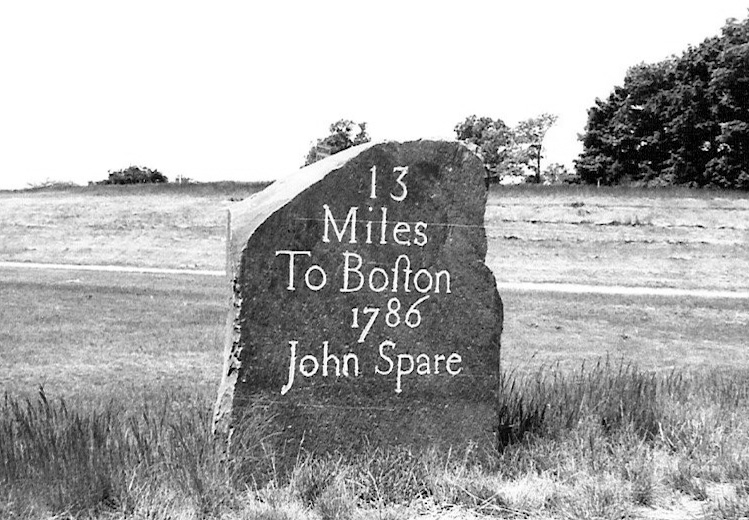

The small cemetery is not the only reminder of the Spare family. Look closely as you pass by the cloverleaf over Route 128 heading towards Blue Hill. Just on the left is a milestone with the name John Spare etched deeply. John was Samuel’s son and was born in Boston in 1737 and brought from Boston to Canton when he was an infant. Brought up in a household that taught obedience, John attended the village school about a mile and a half from his house.

A wonderful anecdote marks a far different time in Canton’s history. When he was about 18 years old, John was returning from putting a yoke of oxen to pasture. Returning home with the yoke on his shoulders, he discovered a bear was following him. “Thinking it was not necessary, under the circumstances, to be encumbered with a load, he threw it down, in order to facilitate locomotion.” On looking back from a short distance he saw the bear licking the sweat of the beasts from the yoke. The location can still be found today in the woods off Elm Street near the stone bridge deep in the woods over the Ponkapoag Brook.

John Spare went on to fight for England during the Battle of Quebec in 1759. He and a neighbor by the name of Jesse Tilson joined the effort by enlisting in Boston. Sailing along with a fleet of 30 vessels, they left on May 12 in a convoy led by a British man-of-war and arrived on June 28 at the Isle of Orleans, opposite Quebec. Powder, shot, shell, cattle, and other livestock were unloaded. Tilson wrote in his diary, “A shot from the enemy killed two of our oxen and cut a spoke out of the wheel.” One day they observed a fire-raft sent down by the French to burn the British vessels. The two men from Canton worked in the commissary and ordnance departments and eventually returned home.

Spare’s ties to England were strong, and the family continued to be active in the Church of England in Ponkapoag until services were suspended after June 11, 1776. Just six weeks prior, the freeholders of that part of Stoughton that is now Canton met at the meetinghouse. The vote was clear — “that if the Honorable Continental Congress should, for the safety of the Colony, declare us independent of the Kingdom of Great Britain, we, the inhabitants, will solemnly engage with out lives and fortunes to support them in the measure.” John Spare was suspected of Tory leanings almost to the end of his life. The American Revolution was an ideal “in men’s minds,” and all that could be said of John Spare was that it “affected his mind later than some, and much earlier than some.” Spare, at age 38, stood shoulder to shoulder with his own son Samuel, age 14 years and seven months, and marched on Lexington on April 19, 1775. After drilling for two days a week, and when the church bells pealed across the Neponset Valley, these Minutemen rapidly answered the call of liberty.

John and Samuel went on to establish the first schoolhouse in Ponkapoag around 1761. This schoolhouse was followed by another built in 1798, and a third — now the Ponkapoag Chapel — built in 1846. The Spare name was associated with many of the early petitions for shares of money for these early public schools.

John Spare’s commerce was in Boston, where he managed his timber and lumber company. This industrious man does not appear to have accepted any prominent roles in public office, and his name does not appear on the petition to divide Stoughton into a precinct, thus becoming Canton. He had 10 children, and sadly two of them died in 1775 within a few days of each other. Hannah died at age 17 and Eunice died ten days later at age 13. Both of these children are buried along with their grandfather and grandmother as well as many other Spares at the forlorn cemetery in Ponkapoag.

Spare lived a long and prosperous life, spending time in both Boston and on his farm in Canton. In excellent health on his 80th birthday, he was at work in the field in Canton when he remarked to his grandson James that he should not live but three years longer. On the last day of May in 1820, John Spare drank ice water on Boston Common; suddenly he fell and was taken to his home on Eliot Street. Six days later Spare was dead, fulfilling his prophesy of death at 83. The coffin was lowered by rope into the ground at Ponkapoag. On that hillside today is a monument erected for the entire family.

John Spare’s lasting legacy is the milestone that was relocated by necessity when Route 128 was built. It is about four feet high, two feet nine inches broad, hammered front and sides, natural rounded top and is hard greywacke found throughout the Blue Hill. Cut by Lemuel Davenport, the stone has been part of our history since 1786. The stone, like the cemetery, stands as a silent and enduring witness to the change of seasons and of the passing of history in Canton.

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=30218