True Tales from Canton’s Past: A Long Term Lease

By George T. Comeau

Among Canton’s oldest and most venerable oak trees are the pair leading to Ponkapoag Pond. (Photo by the author)

First come the chainsaws, growling and ripping through ancient trees. Within days the landscape is transformed into a blank canvas of sand, dirt, and ledge. Then come the heavy equipment ripping and scarring the earth, tossing all that is an obstacle aside. Surveyors move in to flag new roadways; cement castings arrive to become embedded in an invisible thoroughfare for sewage and water. Lots are divided up, and concrete is poured. Houses spring up and new neighbors move in, and Canton booms under the weight of modern progress.

There are examples of this every day here in our lives in this place. When you put it down on paper the changes and growth become staggering. On Pleasant Street nine homes are being built on what was a gently sloping pine grove. Up on Washington Street in Ponkapoag, a beautiful and once proud field is being filled with six small monopoly houses. Up on York Street, deep inside indigenous land, 28 houses are being built on what marketing folks call Turtle Creek — notwithstanding the fact that no turtle will ever again inhabit the nitrate-saturated lawns of these “estate houses.” And the boom is coming to Indian Lane, with more than 90 acres up for development on one side of this small road and 21 acres on the opposite side. Nine more lots at “Cardinal’s Corner” and 17 more at “Stonewood Estates.” We are losing the race for open space, and the tipping point will come as it always has in the growth of the schools, municipal services, tax burden, and loss of habitat to wildlife.

In simple terms, man cannot come to a landscape without changing it profoundly. This is not simply a modern fact; this too happened when prehistoric man built workshops along what is now the Neponset River. Ten thousand years ago these first people hunted along what was once an enormous lake, and they too changed their environment. To suit survival, camps were built, trees were cleared, and tools were manufactured. In the natural state, they could be found hunting, butchering, and skinning herds of animals against a backdrop of first growth forests and lush open grassland.

The effects of man on the virgin landscape in Canton become clear when we note the changes since 1650. While today’s changes are quite profound, they pale in comparison to what happened in the early 1700s when settlers moved into the “wilds of Dorchester.” It is important to note that when the Ponkapoag Indians were settled into the reservation known as the Ponkapoag Plantation, they received their land with the distinct understanding that they were not to sell it. From 1633 onward, the sale of land from the Indians was declared null and void. Sadly, things changed as the Indians began “leasing” their land prior to 1706.

With the arrival of the Puritans in 1629 also came English laws and rules. For the native population, land was not owned, sold, or bartered. Instead, the natives had a fairly transitory relationship with the land. Whereas the English valued everything in monetary terms, the natives shared everything and had no concept of ownership rights. To make matters worse, the English believed that God bestowed New England upon them. The prominent Puritan minister Increase Mather wrote of the property rights as the “Heathen People amongst whom we live, and whose Land the Lord God of our Fathers has given to us for a rightful possession.”

In what is now Canton, 19 men were summoned to appear before the Continental Court on August 18, 1706. These men all held leases from the Ponkapoag Indians — leases that the court would determine the legality of. These settlers all prayed that they would not be severely dealt with, as “they had built their houses and redeemed land from the wilderness.” The court postponed a decision on the matter, simply telling the men that they could not further till the land or build any more houses. By the following year, the Indians waded into the controversy by sending word that they supported the leases on their own land. The testimony presented included the fact that the English neighbors had been very kind to them, protected them in time of war, and were interested in their welfare and comfort. Moreover, the Indians stated that they had more land than they or their children could improve, and the leases were given with consent of the town of Dorchester, from whom they had been given the land.

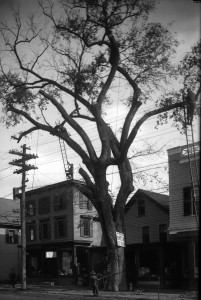

Workmen in Canton Center cutting down an enormous elm tree circa 1905 (Courtesy of the Canton Historical Society)

Over time, the leases simply slipped into deeds, and the English outlived the native population, which had been decimated as a result of contact with European diseases and through acculturation and wars. Large tracts of land in Canton fell into ownership and man began to change the landscape. The changes at first were small. Most notably, the first large-scale change was the clearing of trees to make way for agriculture. By the middle of the 18th century, you could stand pretty much anywhere on high ground in Canton and see clear across to the Blue Hill to the north. Imagine today, standing on High Street or at Canton Corner and being able to see clearly 365 degrees and absolutely no trees in sight.

Today, take note of the few truly ancient trees. There is a glorious pair of oaks on the Ponkapoag Golf Course just to the right of Maple Avenue leading to Ponkapoag Pond. There are a handful of venerable old timers on Elm and Green streets. And as you come into Canton from Stoughton on Pleasant Street, this author spared a Colonial era tree when a subdivision went in at Liberty Place. The girth of these giants is a testament to the time that has passed beneath their mighty limbs.

The next change came in tandem with the clearing of the land — the construction of sawmills that were powered by water. While today we are blessed with numerous ponds, many of these are man-made as a result of building dams to power early industry. Ponkapoag Pond, Houghton’s Pond, and Muddy Pond are likely the only original bodies of water that were here before the 18th century. In 1834, Loammi Baldwin, the father of civil engineering in America, surveyed Ponkapoag Pond as a potential source of water for Boston. Fortunately for us, the ground was too low for an aqueduct and the plan was never considered further.

It is from the streams and rivers that man harnessed the power needed to change the town’s topography. Massapoag Brook takes it rise from Massapoag Pond in Sharon and helped to create Shepard and Silk Mill ponds. The dam at Washington Street enabled this change in landscape to become a powerful source of water for the rise of the silk industry in Canton. In 1834 a canal was cut to allow the water to be diverted to Steep Brook. Industry harnessed and changed the course of Pecunit Brook, Porcupine Brook, Aunt Katy’s Brook, Shaven Brook, Plum Pudding Brook, and countless others that only remain on maps, long lost to daylight through progress.

Most significantly, it was man that created the Canton Reservoir. In the geographic center of town is a “modern” pond. It was called Crossman’s meadow and swamp in earlier times with a strong stream running through the center, fed from York Street and Randolph. In 1720 a dam was erected, followed by another in 1832. Today, this is one of our three Great Ponds protected and available for public use. While today it is affectionately called the “Rez,” in fact it was never a source of drinking water. Instead it provided significant power for the Revere Copper Company. In 2011, it became publicly owned after more than 180 years of private ownership.

We have not only altered the water; we have vastly changed the topography as well. Today’s modern subdivision rules call for filling in large swaths of lowland to bring road heights and grades up to standards. Hills are brought low to meet the same standards. We have been digging and filling Canton for a very long time. Off of Dedham Street was once a place called Pillion Hill. It was named prior to 1720 and resembled the “easy cushion on which our grandmothers rode behind their lords on horseback.” In 1871, a large house was built near the hill to house workers. The site was just to the east where I-95 crosses over the railroad tracks. The steam shovel that had been invented here was used to remove the entire hill of sand and gravel, and once loaded onto rail cars, it was transported to Boston to fill in Back Bay.

From the first moccasins along the Neponset River over 10 millennia ago to the excavator that belches diesel on Pleasant Street today, we are shaping a place that is forever changed by our hands. In time the call will come for a moratorium to take stock, to alter zoning, to imagine better planning that is less reactive and more harmonious to emerging values. Until that time, we sit in traffic that we have created, and develop every last open tract of land. Know that all that we have done is improve land that we still lease. This time, however, we are leasing it from future generations.

True Tales from Canton’s Past appears in the Canton Citizen every other week. Click here to order your subscription today ($25 for one year through October 31).

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=30942