True Tales from Canton’s Past: North to Alaska

By George T. ComeauSeattle was as far away from Canton as the man had been, and here he stood at the meeting point between the great transcontinental railroads and the great trans-Pacific steamship lines. Here was the gateway to an unforgettable journey to unexplored territories in Alaska. This was the life of Winthrop Packard, who explored the Arctic and wrote magnificent stories about natural history that helped inspire a conservation movement that is still strong today.

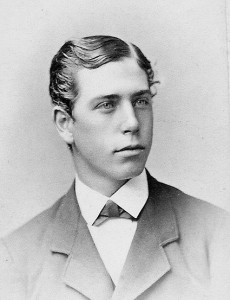

Packard’s father, Hiram Shepard Packard, was born in Stoughton in 1818, and in 1854, at age 36, he married 19-year-old Maria Blake from Canton. The elder Packard was a provision dealer and lived on West Lenox Street in Boston. Birth records show that Winthrop was born in Boston on March 7, 1862. Winthrop’s father died suddenly as a result of pleurisy at age 47, leaving Maria a widow. Returning to bury her husband in Stoughton, it would be a very difficult life for the young mother and her 4-year-old boy.

Fortune, however, has a way of smoothing out the travails of life. In 1870, back in Canton, Maria met and married another older gentleman, this time a very healthy and hearty man named Samuel Bright. At age 57, Bright was an accomplished builder and carpenter, and many of his houses are still standing today. He was also a widower, his wife, Clarissa, having died in 1868. So the beautiful young widow with a young boy moved into a handsome house, and the old builder ardently loved his young wife. When he was 58, Maria gave birth to a daughter, and then when he was 61 she gave birth to a son. In 1888, Samuel Bright died, leaving his widow and his two teenage children along with his stepson Winthrop.

By this time Winthrop Packard had already graduated from Canton High School in 1879 and attended MIT, where he studied chemistry. In 1880 he is listed in the census as a teacher, likely here in Canton in the public school system. He was at MIT from 1881 through 1883, and it is unclear whether he actually graduated from there. Packard’s early career was in chemistry, yet he was a writer at heart. In the early 1890s he began writing for magazines and submitting articles for publication. By 1894, he became the editor of the Canton Journal. Editing his hometown newspaper was likely quite mundane for him, but he was working on several other projects at the same time.

In particular, he wrote lyrics and published music that today only lives on in the archives of the Library of Congress. One quite comical and romantic song was entitled “The Shoogy Shoo” and tells of the love between a “lassie with hair of tangled gold above an Irish brow” and ends with the come-hither line, “Come nestle in my arms and swing upon the shoogy shoo.”

“The Shoogy Shoo” was published as a poem in 1897 and released as a song that same year. The music was for piano and featured glimpses into nature, including a line about meadowlarks and swinging among the breas. The early description of the Shoogy Shoo described the word as Celtic for seesaw. The song sold quite well, and Packard began to turn his career towards more serious writing.

At the same time, Packard served for three years in the Massachusetts Naval Brigade and participated briefly in the U.S. Navy during the Spanish-American War in 1898. Already becoming an ardent environmentalist, Packard traveled and was published extensively in nationally syndicated magazines and newspapers.

In 1900, Packard signed on as a correspondent for the Boston Transcript, the New York Evening Post, and the St. Paul Dispatch. He was 38 years old, unmarried, and had already established himself as a writer, having cut his teeth as an editor and author for the Youth’s Companion — an important family magazine of its day. The assignment would forever change the course of his life. Packard signed onto the Corwin Expedition to Alaska, Siberia and the Arctic.

Explorers came to Alaska for a variety of reasons. Traders, trappers, and prospectors wanted access routes to fur and mineral resources. And the Corwin Expedition was among the last of the expeditions up the coast in search of coal and minerals. Studying Alaska’s geology and environment was of great interest to scientists, and a group of Boston investors were particularly interested in seeking out coal. Named for the ship Corwin, a retired revenue cutter, this was a trip to the furthest reaches of unexplored America. Packard would be the writer to set young minds on exploration into the vast unknown.

The Corwin was the same ship that the U.S. government had been using as an ice cutter for many years, and the very same one that John Muir had explored the Arctic on in the 1880s. It was no coincidence that some of America’s earliest nature writers fell in love with the Arctic. The exposed beauty and vast landscapes were untouched and pristine and held untold fortunes for discovery. The Corwin had been built in Abina, Oregon, of the finest Oregon fir, fastened with copper, galvanized iron, and locust tree nails. Her draught was 11 feet with a 24-foot beam and was 137 feet long. Principally, her duty was to enforce federal laws and protect the interests of the country in the Fur Seal Islands and the sea otter hunting grounds of Alaska.

Packard would have joined the expedition in Seattle, likely in June — the best season to explore. It would take 10 days to travel up the coast to Nome, where final preparations were made. With the ice pack in retreat, the shores were green with vegetation and “strange mirages making the low shores of the Seward Peninsula loom up like fantastic dumb-bell shaped mountains.” The mission behind the expedition had a strange twist that only now seems archaic and misguided. The Corwin Trading Company was engaged in the systematic attempt to develop coal deposits in the north and bring the coal to Nome to be used by an enormous whaling fleet that previously would have had to travel to the Puget Sound to get fuel.

In opening up the Alaskan coal fields, the Corwin Trading Company stood to profit handsomely from the whalers that would cruise the Arctic Ocean. Packard, however, used every opportunity to explore and describe the nature of things that he encountered.

“I went back on a long twelve-mile jaunt into the interior one day, tramping due south from the sea, climbing from ridge to ridge in places where surely no white man’s foot had never set before. The bare tundra was a desolate and lonely place as one could wish to find. No bush, no tree grew there. Even the creeping willow that you find farther south was wanting. Yet every little valley had its carpet of green grass and was spangled with flowers. No animal moved on the hill or plain. Only the hawks that breed on these hills sailed over my head in scores, so curious and fearless that I could almost reach up and touch them … Twelve miles to the southward I climbed an isolated peak and in the marvelously clear arctic air could see scores of miles all about me. Lakes and rivers lay below, to the north the blue sea with its distant fringe of ice floes, while inland range on range of snowy capped mountains lifted to the far interior.”

Here was Winthrop Packard, standing alone with “no tree, no man, no beast” in sight, soaring hawks, “a snowy bunting, and sitting on the shady side of the peak blinking solemnly, a great snow white arctic owl.” And on that peak, Packard did what man can never resist — he left his mark. “On a great slab in the sandstone I spoiled one blade of my knife carving my name and the date.” Marking his name forever in that desolate place that likely no man will ever see again, yet we know it is there.

After Packard returned, he began writing voraciously. Inspired by his Arctic expedition, he wrote “The Young Ice Whalers,” a fictionalized account of a boy from Quincy traveling to the Arctic. The book sold very well, and Packard turned to several more books, all focusing on nature. The titles and subjects were heavy on New England themes, and many stories featured Canton as a backdrop. “Wild Pastures,” “Wood Wanderings,” and “White Mountain Trails” were all well received and sold briskly.

Packard became the secretary and treasurer of the Massachusetts Audubon Society and personally financed and established the Moose Hill Bird Sanctuary in Sharon. His long life in Canton was blessed by the marriage to his wife, Alice, who had been married to a Unitarian minister but was left a widow when he died at a very young age. Packard’s three children all went to Canton schools and did quite well in life — one joined the U.S. Navy, another became a science teacher. Packard died in Canton at age 81. The house he lived in on Washington Street is still standing.

It is amazing to think that the environmental movement in America started as early as the late 1800s and that Packard is mentioned in the same breath as John Muir. Yet they were both powerful writers, and Packard was part of the early development of the Audubon movement in Massachusetts, which today is the largest and most prominent conservation organization in New England.

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=31125