Canton True Tales Revisited: Colonial Vaccers

By George T. ComeauThis story originally appeared in the Canton Citizen on November 12, 2015. It offers a glimpse into an early public health crisis and is being revisited with the hopes that it can serve to illuminate and educate as the community grapples with the impacts of the COVID-19 outbreak.

Thirteen years had passed since the visitor had made an appearance in our town. Off and on, there were short isolated visits, but quite unlike the visit in the spring of 1764. The caller silently slipped into town, unaware and hidden behind a dark cloak of mystery. The constables and selectmen were on the lookout, yet still it made no matter. The damage would rage.

Into many houses in Stoughton, in what is now Canton, the visitor brought pain, sadness, and ultimately death. The diary of Elijah Dunbar records the scene: “Vilet died this night, a very terrible time. Leonard’s folks taken. Mrs. Vose dies. Old Joseph Fenno dies. Polly Billings dies of the purple sort. Sunday, Mrs. Davenport dies. Fasting on account of the great sickness. Poor Mrs. Leonard dies this forenoon, and Wally this afternoon. Nurse Howard dies. Ebenezer Talbot dies.” Many of the dead were taken to a small burying ground in the Hardware section of the town. They all died of smallpox.

Just after the waterfall at Shepard’s Pond, on your left is Kinsley Place, a small street that dips down a slight hill. To your right is a tiny field, and here is where the dead were buried. There are no headstones, although there were several there in 1893. Folklore suggests that the stones were removed and became parts of doorsteps in the neighborhood. That said, we have a few records to suggest who was buried there — women, children, and men from the community who all died an agonizing death.

Smallpox is one of those diseases we usually only hear about in historical records. We know that when Europeans came to the New World, they infected the native population so thoroughly that by some estimates 80 to 90 percent of the population was killed off. In many cases, entire villages in our region were so decimated that there was no one left to bury the dead.

Because the disease is foreign to us today, modern understanding is largely relegated to stories of the sickness and the advances that fully eradicated it from the globe. Smallpox is a highly contagious infection that is caused by a virus that can be fatal to young children and young adults. It was spread by saliva, but it also remained alive on bed sheets, blankets and clothing. As a result, the disease proliferated through entire families and their caregivers and hit especially hard in close-knit communities and the tribes of the natives.

The epidemic of 1764 was sinister. A note was sent via a courier to the town of Bridgewater warning the residents who were coming to Stoughton to attend a singing meeting that they should “not come over.” The deaths shook the community and resonated in many of the surrounding cities and towns. Only late in the summer, after almost a dozen had been buried, did the epidemic subside. And while there were flare-ups, things remained quiet until 1775.

As hostilities began heating up in the infancy of the American Revolution, the British may very well have engaged in biological warfare, and what’s more, General Washington was aware and took steps to manage the disease throughout his army and the colonies. Several modern biological weapons experts and historians agree that the British troops in North America deliberately spread smallpox to control hostile Indians in the 1760s.

We know of the story of Sir Jeffery Amherst, commander of British forces in North America, who, confronted with a native uprising, wrote on July 7, 1763, “Could it not be contrived to Send the Small Pox among those Disaffected Tribes of Indians? We must, on this occasion, Use Every Stratagem in our power to Reduce them.” He ordered the extermination of the Indians and said no prisoners should be taken. About a week later, he wrote to Colonel Henry Bouquet: “You will Do well to try to Innoculate the Indians by means of Blanketts as well as to try Every other method that can serve to Extirpate this Execrable Race.”

And so, as war began, the British once again used every tactic at their disposal, including employing smallpox as a deadly and effective weapon. While a true inoculation did not come into use until the late 1790s, a form of managing the disease called variolation was in use as early as 1721. Under the guidance of the Rev. Cotton Mather and Dr. Zabdiel Boylston, variolation became used in the colonies. The technique was to take pus from an infected person and insert it under the skin of an uninfected one; that gave the inoculee a mild case of the disease and, after the passing of a period of high communicability, lifetime immunity.

Mather, a graduate of Harvard College, was a man of science and medicine. When a ship from the West Indies brought smallpox to Boston in 1721, a widespread epidemic broke out throughout Massachusetts. Mather wrote a cautious letter recommending immediate variolation. However, only Dr. Boylston took up the controversial act. With Mather’s support, Boylston immediately started a variolation program and continued to inoculate many volunteers, despite many adversaries in both the public and the medical community in Boston. As the disease spread, so did the controversy around Mather and Boylston. At the height of the epidemic, a bomb was thrown into Mather’s house. Early vaccinations were controversial and dangerous practices that only slowly took hold as accepted practices.

By the time that the war began and certainly by 1775, the British defending Boston from the rebels had already inoculated all their troops. When smallpox broke out in the town, the British sent recently variolated civilians among the besieging colonists, causing an outbreak that delayed the eventual American victory. While variolation was effective, the recently inoculated were surely highly contagious, and as a result the disease spread to those not treated. One in three that became infected would die, and because smallpox was common in England, most British soldiers had already been exposed and were immune. But with the disease less common in America, the exposure to the population would become a means to slaughter the continental soldier.

Throughout the fall and into the winter of 1775, an outbreak raged through Boston. When the British finally evacuated the city in March 1776, only soldiers who had already had smallpox were allowed to return to protect the city. General Washington ordered his doctors to watch for signs of smallpox and to send infected soldiers to an isolation hospital immediately.

The question to inoculate was championed by such scientific pioneers as Benjamin Franklin and was undergone willingly by John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and other leaders. Yet, for the general public, it was unsafe because the patient had to be isolated for a week prior to the inoculation and two weeks or more after it. The Continental Congress had forbidden military doctors to administer it and forbidden army officers to take variolation or have their subordinates do it “on pain of being cashiered.”

Washington faced a dilemma — that being whether to systematically inoculate healthy soldiers or to follow the orders of the Continental Congress. It was only a matter of time, and in February 1777, after 18 agonizing months, Washington became convinced that only inoculation would prevent the destruction of his army. In secret, Washington ordered the inoculation of all troops. The commonwealth of Virginia forbade inoculation, and urging the governor, Washington wrote that smallpox was “more destructive to an Army in the Natural way, than the Enemy’s Sword.”

In the spring of 1777, the Continental Congress, acknowledging General Washington’s success with mass variolation, issued a formal inoculation order. Before the end of 1777, nearly 40,000 troops had been inoculated. In the year following the start of mass inoculation, the infection rate from smallpox in the Continental Army fell from 17 to 1 percent. Inoculating the American troops safeguarded the army from being decimated by disease, making it possible to turn the tide of battle in America’s favor.

Here in Canton is preserved a relic from this time and the decision that runs contrary to the wishes of General Washington. “In the name of the government and people of ye Massachusetts State you are required to warn ye freeholders and other inhabitants within your limits of the 2 precincts of this town that are qualified to vote in town affairs to meet at the meetinghouse in the first precinct of this town on Monday ye 7th day of July next at 3 o’clock in the afternoon to confirm and act on the articles hereafter mentioned.”

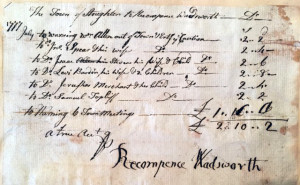

The billing statement from Constable Recompense Wadsworth for warning residents about the July 1777 town meeting

Here we have a handwritten town warrant handed to Recompense Wadsworth, the constable, who was charged with spreading the word of the upcoming town meeting. The purpose of that meeting was clear: “to see if the town will take any further measure to prevent the spreading of that dreadful distemper ye smallpox in the town.” And the warrant went even further — and seemingly against the science — “to see if the town will take any measure to punish those who have contrary to ye repeated votes of this town in defense of its authority dared to permit their children to be inoculated or any that have been inoculated themselves or any that have been hiding and assisting therein.”

There were two additional articles that stand out on that warrant, the first being the suggestion that the selectmen were to be examined as to their conduct on the matter of allowing inoculations, and to examine whether they were properly “warning people out of town — as they are in duty — bound.” The issue being that the selectmen may not have taken the threat of smallpox seriously enough and were not ordering “outsiders” or transients from the town limits. Ultimately, the town meeting voted to allow a committee to oversee the handling of smallpox, and within the following year hospitals were set up for inoculation, “Voted to Limitt the time of inoculation to ye 25 day of June next. Voted that the number of ye hospitals be left with the Selectmen.”

Here in this one document the world of medicine, politics, and colonial warfare collide. The record suggests that the elders who drew up the town warrant were quite concerned with the spread of the disease, yet at the same time against the idea of vaccinating their children. Within a year following the success of General Washington’s inoculation of the troops, the tune had changed.

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=31440