True Tales from Canton’s Past: Native Tongue

By George T. ComeauAs time erases more and more of our earliest history, it becomes even more incumbent upon us to preserve our place names that respect the original people who lived here. It seems so ironic that in this particular place in our history today, we are wary of immigrants, outsiders, and refugees, and yet hardly any of us can trace our own blood to anyone but such peoples.

John Eliot, the “Apostle to the Indians,” recorded many of the people and places that are native to Canton.

As a society, we tend to reform history to suit our comfort with atrocious facts and today’s norms. It is, however, an inescapable circumstance that the place we live today was long inhabited before Europeans arrived in the middle of the 17th century. We have always been a country of immigrants and refugees. And we look to the earliest contacts and what was written and passed down through folklore to understand the sacred places that still can be traced in our town.

We like to think that the Ponkapoag Indians were the first to be settled here, yet this is a grave error in historical thinking about Canton. In fact, ancient people lived, worked, and hunted on this land close to 13,000 years ago. Imagine the fact that our history is absolutely that old, and we are mere specks in that timeline. We know through archeology and well-founded scientific research that the area that is now Canton was extremely important to the native people. There are several worksites, campsites, and trading places that are still readily accessible to visitors today.

They are, however, the names and words of the people that our language and community has unconsciously erased over time. We know that John Eliot was working to Christianize the natives here as early as the mid 1650s. And it was Eliot who brings us great understanding of the language of the native people. It all started with the Bible.

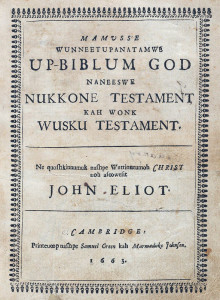

The history of Eliot’s Indian Bible is one of the first major elements in the conversion of the natives to begin a process of assimilation. Key to this plan was the importation of the first printing press to the colonies from England so that religious material and Puritan writings censored in England could be produced. Stephen Day was hired by a wealthy patron in England to travel to the New World with his press. Arriving in Boston in January 1639, Day started the operations of the first American print shop, which was the forerunner of Harvard University Press. The press was located in the house of the president of Harvard College, where religious materials were published in the 1640s. In 1659 the printing operations were relocated to the Indian College at Harvard when a new printing press was obtained. It was here that Eliot’s Indian Bible was printed.

Eliot’s job was to bring the word of the Lord to peoples whom the English viewed as savages. And his instrument to do this were the Christian scriptures. Eliot’s sense was that the natives felt more comfortable hearing the scriptures in their own language than in English. Thus he studied the Algonquian Indian language of the Massachusett people so he could translate English to the dialect of the native tongue. Eliot translated all 66 books of the Bible to Algonquian in a little over 14 years. He had to become a grammarian and lexicographer to devise an Algonquian dictionary and book of grammar. Many of the natives who assisted Eliot were right here in Canton. And so the writing of Eliot becomes key to our understanding of the language of these people and to the places that we know today.

The final say on much of the original names must turn on John Eliot’s writings. James Hammond Trumbull was one of the greatest native language experts and whose best-known work was that on Indian languages. Trumbull wrote, “A Massachusetts name written by John Eliot may safely be assumed to represent an original combination of sounds, more exactly than the form given it by some recorder ignorant of the Indian language.” Over time, we have erased or obliterated much of our original names and places.

Let’s start with Chicataubut, the sachem of the Neponset Indians, whose name is said to signify “a house or wigwam on fire.” This was the man who the Pilgrims would come to know, and the land he and his people ranged was all of the area between Boston, Canton, and down through Plymouth. Today we spell it Chickatawbut, but there are several historical spellings that date back as far as 1633 — all quite different, but all preserving the sound of the name. The wisdom of the spelling through the ages was to preserve the sound since the natives did not have an alphabet as such.

There was also Kitchamakin, the successor of Chicataubut and in whose wigwam Eliot first preached in 1646. The name was spelled so many ways — Cutchamakin, Kutchamakin, Kutshamin, and Zuoshamakin. When you say them out loud, you get the idea of the difficulty that faced the translators, who could say the names but had no reference as to how to spell the name. The same is true of the Neponset River. The Reverend William Hubbard wrote of this place in 1680 and called it the Narponset. Another contemporary of Eliot, Daniel Gookin, called it Neponsitt. It was also called Norponsett and sometimes simply Poncet.

Then there is Pigwalket, an ancient native path that led through York Street and into East Stoughton. It is said to be a word that translates into our language as “a valley” or “land of hollows.” The same name in fact was applied to other areas of New England and Pequawket is the Abenaki name for Fryeburg, Maine, and the Abenaki name for Kearsarge North in the White Mountains.

Many of our meadows have been lost to development, but the ancient names are simply wonderful and amazing. Moughawge Swamp — a name thought to have been derived from the word Mohawk. Concanpeimshon was the name for Cedar Swamp and Pommochum’s or Pummechum was another long-lost meadow. Today we use the word Pecunit for both a street and brook that runs through our town. Originally this was spelled variously as Pacqunit, Paicunit, Pacunit, Pocunit, and as early as 1696 as Pecunet, which was applied to the western portion of Horseshoe Swamp. Again, when you speak the names you see the various ways that the words translated into the current iterations. In 1700, the selectmen of Dorchester mention Pecunet as the “rising of a steep hill” between what was Ridge Hill and Canton Corner.

A sign that marked the boundary of the Ponkapoag Plantation from 1930 was stolen earlier this year and never recovered.

There is an ancient verse written by the Reverend Theron Brown that reads, “Down from the Sharon Uplands sweet, and east through Ponkapoag ravine, O’er the same beds of mossy green and sparkling with their vaunted gleams, falls Massapoag and Pekameet.” This is the Pequit Brook and today it runs through Pequitside Farm, through Pequit Meadows and down below Pequit Street.

These native words were all tongue twisters for the English, and so when confronted with people they simply came up with new names out of whole cloth. Old Zuashaumit who lived near the foot of the Blue Hills was named William in the early deeds that transferred the land he lived on into property the English could trade. The Anglicizing of people’s names became quite common, and Quaanan became William Ahauton, his brother Natoogus became Benjamin, and his sisters, Tahkeesuisk and Jammewruosh, likely lost their names as well.

And yet if we follow the advice of Trumbull and closely track the writing of Eliot, we may one day reform our spelling of Ponkapoag. In a letter in 1657, Eliot wrote to a friend, “You approve and allow the Indians of Ponkipog there to sit down and make a town.” That town became known as the Ponkipog Indian Plantation. Thirteen years later, Eliot again writes Ponkipog, showing that he had seen no reason to change his original method of spelling the name. Three hundred and fifty years later, we still spell it wrong, and that is hardly progress.

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=31827