True Tales from Canton’s Past: Cows & Dogs

By George T. ComeauIn a meadow, he stepped lightly, avoiding the obvious signs of bovine leavings. In the heat of the late afternoon, the sun was declining and casting long shadows over the pasture. And as he cleared the thicket, he saw the elegance and grace of the herd at rest.

He wanted to capture them in this most perfect setting — their slender bones and almost deer-like stature. Docile and passive, they stared aimlessly across the Ponkapoag countryside. The colors were fantastic, the blues and greens of late summer, and the shimmer of light across their flanks — a quick sketch, a moment’s glance, and the artist had what he needed. Stepping back, Thomas Hewes Hinckley was taking his place as one of America’s foremost “barnyard artists.”

While it’s true that Hinckley was mainly renowned for his paintings of cattle, dogs, and hunting vignettes, he actually became a great American artist, and he did it from one place: Milton, Massachusetts. And though we cannot claim him as our own, Hinckley’s work intersects with the town of Canton in wonderful ways. For it was the pastures and fields of Canton against the backdrop of the Blue Hills in which he found his calling.

The Hinckley genealogy is long and full of rich stories. As old as New England itself, the Hinckley family can trace itself back to Thomas’ grandfather four times removed, also named Thomas. Thomas Hinckley was baptized in 1618 and came from Kent, England, sometime around 1634. Rising up through the political aristocracy, Hinckley became the 14th governor of the Plymouth Colony and held several other highly ranked governmental positions during his lifetime.

The reason the Hinckley lineage is long owes partly to the fact that Thomas Hinckley married twice — first in 1641 to Mary Richards, and again to Mary Glover in 1659. He may have had as many as 17 children; different sources disagree on the exact number. One of his children, Samuel Hinckley, was a direct ancestor of presidents George H. W. Bush and George W. Bush. Thomas Hinckley’s sister, Susannah Hinckley, is an ancestor of President Barack Obama, which means that Thomas Hinckley’s father, Samuel Hinckley, is the ancestor of three U.S. presidents.

Subsequent generations were equally illustrious. Thomas’ grandfather was Thomas Hinckley II, and family lore tells the story of how he swam ashore after escaping from a British prison ship only to die during the American Revolution “after eating peas boiled in a copper kettle.” Thomas’ father was Captain Robert Hinckley, the master of the passenger ship Galen, who was forced to retire from a life at sea after taking an opiate for sleep and upon morning discovered he was completely deaf. The captain retired to a small farm in Milton quite near the Blue Hills.

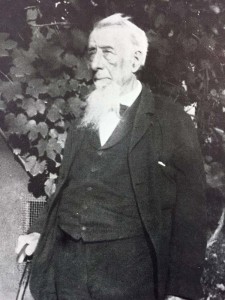

Thomas was born in 1813, in the same house he would die in 83 years later. Long gone, the house was located where Brook Road meets present-day Ridge Road. At age 15, Hinckley was sent to Philadelphia to work as a clerk and learn the life of a mercantile agent. Yet a boy of 15 in a wonderful city like Philadelphia is likely to wander, and in doing so, Hinckley began attending evening art classes taught by William Mason. The only formal art training in Hinckley’s life were those courses that he took over the three years he was away from Milton. Hinckley would comment later that the instruction under Mason “opened the world to him.”

The world in Hinckley’s eyes was as far as the eye could see. The young artist settled on landscapes and in particular animals, and of that ilk, it would be wealthy owners of dogs and cows that would bring him fame and fortune. The die was cast as early as 1838 when he painted a picture of a spaniel dog for E.J. Baker, a neighbor who lived less than a mile away. This was followed up with portrait of a female dog with her pups, purchased by a wealthy resident of Roxbury. By 1840, Hinckley was making a name by painting dogs of the wealthy, and there is a wonderful sketch of the period at the Milton Historical Society called Dogs of Milton Village, and we see Nap, Bruno, Ino, Red Mill Dog, Skip, Don, Chief and Spottie. And there they are — English pugs, black and tan terriers, a mastiff, and a spaniel. Eight dogs immortalized forever on a dusty road in Milton.

Many of Hinckley’s paintings feature the Blue Hills. The fields in and around Canton as well as Milton were particularly favorite spots in which to set his scenes. For while there are examples of portraits that he painted, it is his paintings of cattle for which he is perhaps best known. The wealthy gentlemen farmers spent large sums of money on their prize herds, and having them immortalized and hanging in their sumptuous parlors kept the young painter very busy.

Perhaps the most important commission that Hinckley ever brokered was the one we know the least about. In 1845, Daniel Webster asked Hinckley to his farm in Marshfield. Webster, at that time a U.S. Senator, owned a collection of Alderney prize cattle as well as Ayrshire cattle, Devon oxen, prize sheep, guinea hens, peacocks, Chinese poultry, and two South American llamas. It must have been an amazing experience to sketch on that farm. For an artist whose passion was livestock, here he was with the finest animals in America, working for one of the greatest political men of the ages.

Commissions seem to have come easily to Hinckley, and he painted 20 to 25 paintings a year — about one every two weeks. In his lifetime he is credited with 478 paintings. He had a small studio and preferred to sketch on location and bring the sketches back to paint them in his “sanctuary.”

What is also amazing about Hinckley is that we know so much about his life because he created extensive notes and account books in which every minute detail is recorded. The records do not merely account for his art, but also his everyday life. The sale of eggs, chickens, and the purchase of strawberries and other sundry items, all meticulously recorded throughout his life. Even the pig, which weighed 200 pounds, was killed and yielded $12. It is, however the paintings that are most carefully recorded, art and commerce together in tabulated columns. An early account book gave way to a new one in 1844, when he copied over all his previous entries and created a single book, which ended in 1884.

The art sold well and was highly sought after. Generally speaking, a painting done by Hinckley sold for around $125. Some of his more elaborate paintings sold for more. In his records he indicated that in one instance he accepted a gold watch in exchange for a painting. In another transaction he painted a portrait of “Fanny,” a setter, and was paid in exchange for one of her pups. Today, the range for the paintings can reach more than $50,000, and while several pieces are for sale, most of the art is now located in museums across the United States. Of course, private individuals throughout the greater Boston area may very likely have his artwork in their estate homes, passed down through the generations.

But perhaps the finest example of Hinckley’s work is actually owned by the people of Canton. Hanging in the reading room at the Canton Public Library is a stunning landscape with cows in a pasture and the Great Blue Hill in the distance. This painting was done in 1878 and may very well have been donated by one of the wealthy patrons of Hinckley. It is worth a visit to see the bucolic idealism of our town as it once was and is now forever captured as a reminder of Canton’s past.

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=32577