True Tales from Canton’s Past: I Am the Egg Man

By George T. ComeauHiking across the marsh, Elwyn Capen had endured several days of torrential spring downpours, yet he was in his glory. Soaked to his skin, a heavy wool coat slowed his progress as he approached the nest just at the edge of Ponkapoag Pond. High up in the tree was the large nest of a great blue heron, one of several that comprised this rookery.

Capen began his slow and careful climb; fearing a fall, he was always planting his feet firmly from branch to branch. A swift wind picked up from the north and his face was pelted with rain. Peering into the nest, he quickly plucked one of the six pale blue eggs and placed it inside his satchel full of dry hay. Minutes later, and back on the ground, Capen made his way to his home. Another specimen intact and ready for study in what would become a seminal work in American oology.

Elwyn Andrew Capen was born into a fairly well-off family. His mother, Clarissa Bussey Boyden, was from Dorchester and had married George Capen, whose family had been in Canton since the early 1740s. George was a prominent man who had been on the School Committee as well as serving as the town treasurer and a state representative. George’s father, in turn, had been born in a tavern at what is now Canton Corner and had also become quite prominent. He too was a state representative and was a wealthy hat manufacturer and the director of the Neponset Bank.

Elwyn’s life changed dramatically when he was only 6 years old. Samuel Capen, Elwyn’s grandfather, died in January of 1863, and then three weeks later, Elwyn’s father died. Clarissa was left to raise six children on her own. The deaths were tempered by the fact that the multiple inheritances from the husband and father-in-law left Clarissa considerably wealthy. The 1870 Federal Census recorded Clarissa’s wealth at over $30,000. Adjusted for today’s dollars, this would be a standard of living worth more than $500,000. When you look across the town of Canton in the 1870s, the Capens were wealthy by anyone’s standards.

Elwyn Capen attended Canton High School and completed three years of study and finished in 1875. Soon thereafter, he attended William Eliot Fette’s private school for boys in Boston. By 1883, he had gone into the relatively new business and science of taxidermy. Pairing up with another Canton fellow by the name of Pertia Aldrich, they became Aldrich & Capen and had a very successful business on Washington Street in Boston.

Taxidermy was in enormous demand, and by all accounts, Aldrich & Capen were among the best in America. “The magnificent groups of mammals and birds in the American Museum of Natural History, Central Park, N.Y., tell of the profound ability … the groups in our National Museum, Washington, D.C., also stand as lasting monuments to the ingenuity and skill … and among those who have likewise been identified with the recent progressive period in American taxidermy may be mentioned the names of P.W. Aldrich and Elwin A. Capen.”

At the height of the science of preserving animal specimens stood these two men. They, along with their peers, were described as having “gone into the rich fields of nature, turned from the narrow trodden paths and plucked flowers whose beauty was never before seen. They have discovered and reproduced new scenes such as were never carved in stone or painted on canvas.” And the work they did was stupendous. By 1883 or so, they had sold their Boston business to an even larger supplier who expanded the business to include the sale of specimens “from all parts of the land, mammals, birds, heads, land and marine curio, mats, robes, horns, antlers, eggs, nests and everything that comes under the head of natural history specimens.”

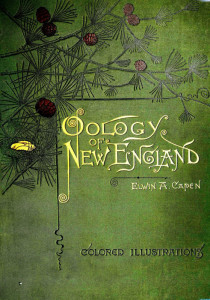

Back in Canton, Elwyn began an enormous project of cataloging and drawing eggs. At the urging of a close friend, he took up the task of creating a handbook for oologists studying the birds that migrate to and live in New England. Oology became increasingly popular in the United States during the late 1800s. Observing birds from afar was difficult because binoculars were fairly expensive and not readily available. Thus it was more practical to shoot the birds, or collect their eggs. This was no easy task. It took years to accomplish and was extremely ambitious in scope. This book became an account of the eggs, nests, and breeding habits of any bird that at the time was known to raise their young in New England. Capen had even grander plans — that of completing a work for all the species of North American birds. That was not to be.

When it was published in 1885, Oology of New England sold briskly. Copies sold for $15, and within a year the edition had been mostly exhausted. Today, a copy can fetch more than $1,800. The book contained beautifully colored plates rendered delicately by advanced chromo-lithography. The eggs “are all figured the size of nature, and in a great many instances, several illustrations are given of each species.” But despite his efforts, the book contained a few issues that experts looked askance at. “Take for instance his figures of the eggs of the Marsh Hawk (Circus hudsonius),” wrote a critic. “The illustrations represent two eggs, both of which are distinctly spotted, when the great majority of eggs of this species are wholly unspotted.” Ah, critics. They always have a shell to crack.

While being a taxidermist and oologist was exciting, at the same time Capen had turned his attention to other interests. In 1887 he purchased jointly the exclusive rights to sell the goods of the Canton Patent Knitted Factory on Chapman Street. And then less than two years later he turned his attention to chemistry. There is no record of Capen formally studying chemistry, but despite this fact he developed a special formula for “blacking.” The shoe industry had been transformed and Capen sold a black liquid paint that was used to dress leather. In 1891, Capen purchased the land where the Hellenic Nursing Home is today and built a factory called the Crow Blacking Company. The company grew and became quite successful throughout the region. Over 1,000 barrels were used in the United States and exported to Mexico and Australia.

Money seemed to flow easily for Capen, and in 1892 he set off to Wyoming, likely to visit his sister Eliza, who had married George Frederic Chapman and had settled thousands of acres at the Neponset Land & Livestock Company. Newspaper accounts share the fact that while there, Capen went “egging” and returned with fine specimens of eggs.

By 1895, Capen married Mary Louise Morrison from Yonkers, New York. The following year they had their first child. Over the next several years they had three more children, including one who died very young.

Capen spent his life largely here in Canton. He became involved as a trustee of the Canton Public Library and a volunteer fireman for the Reliance Hose Company at Canton Corner. In 1900, Capen and three close friends founded the Wampatuck Country Club. And then in the summer of 1904, tragedy struck. In late June severe abdominal pain caused Capen to take to bed. Within a few days his appendix was removed. But the damage was done — sepsis set in and within a week the naturalist, artist, chemist, and manufacturer was dead. “In the prime of a useful and successful life,” he was carried to his final resting place by his closest friends and family.

Capen’s brother George took over the factory, and the business became an enormous manufacturer of patent leather. The success of the Capen family enabled them to buy W.A. Davis Ink, the same company that had supplied the ink for the U.S. Post Office and the U.S. Treasury.

In the summer of 1908, as Mary Capen planned to move to Alameda, California, she opened a large box that had been stored in the attic of the family home on Washington Street. Inside she carefully traced her hands over the creamy paper. Here were uncut, untrimmed, unbound copies of her husband’s masterpiece. Each copy had been assembled and was ready to be bound. These last unbound books were a link to her life in Canton, and so she had them encased in special boxes and they sold briskly to collectors who knew the value of the man and his work.

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=32735