True Tales from Canton’s Past: Devoted Servant

By George T. ComeauThere is an old and little used adage that today, fortunately, has very little utility: Behind every man there is a woman. And indeed there was a time when it was entirely true. No truer than the woman that was behind Dr. Harvey Cushing — in his day the most famous neurosurgeon in the world. The woman was Madeline E. Stanton, and she was his secretary until his death in 1939. The story of her work beyond the life of the man is a lasting and indelible mark on the history and literature of medicine.

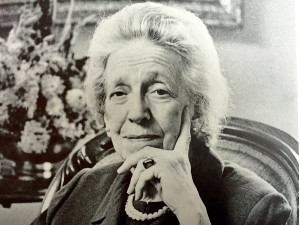

Madeline Stanton in the office of Dr. Cushing, Boston, 1932 (Center for the History of Medicine: OnView)

Madeline Earle Stanton was the younger of two daughters born in Canton to John and Mary Stanton. John was in the employ of the Revere Copper and Brass Foundry where he worked maintaining the railroad tracks and in the carpentry shop. The small family lived on Washington Street and Madeline attended the Canton Public Schools, graduating from the high school in 1915.

There were only 28 graduates from Canton High that year, four of them men. For the women who graduated, most of them stayed home; a few became stenographers; and others became teachers or nurses. The men of that class went to Harvard, Exeter, or a preparatory school. Madeline went to Smith College in Northampton, graduating with an AB cum laude. After a brief stint as the secretary to the director of the Boston Pops Orchestra, she became the secretary to Dr. Cushing. The year was 1920, and Cushing was at the height of a brilliant career.

Neurosurgery was quite nascent, and it would be an understatement to say that Cushing’s brilliance was matched by anyone at the time. The men and women who worked at Harvard Medical School and Peter Bent Brigham Hospital were global rock stars. In 1925, Cushing introduced the use of electrocautery to control hemorrhaging during brain surgery, and invited many patients on whose tumors he had earlier been unable to operate to return. Also in 1925, Cushing published his large two-volume Life of Sir William Osler, for which he won the Pulitzer Prize in Letters in 1926. The science of modern medicine was being built upon the seminal research of physicians that dated back centuries. And Cushing was a collector of books and rare medical manuscripts. Madeline would take charge of the collections and organize Cushing’s life.

The days were endless, the energy invigorating. Cushing was working with John Fulton, an eager Rhodes scholar from Minnesota, and together as a hobby they collected old and rare medical books. Fulton impressed upon Madeline the habit of keeping a diary. And here is where she shared a “phenomenally crowded and productive existence” inside the world of Cushing. Madeline’s biographer wrote, “Miss Stanton during these years led an exceedingly strenuous life which demanded every ounce of her considerable strength.” Stanton’s life was Cushing’s life, and she served “the chief” in every moment of her day.

A friend of Madeline once said, “Today in an age when self-fulfillment is frequently described as a desirable goal for individuals, and especially for women, we may find it difficult to appreciate that Madeline did not seek in her life to fulfill herself. She lived for purposes apart from and beyond herself. Her aims in life were not revealed by anything she said — she was plain and unassuming in speaking of herself — but they were supremely evident in what she did.”

And what she did was amazing. Her early career was occupied by working six days a week in Boston. During these years she developed an interest in book collecting and began to gain that knowledge of early and rare medical books. Several times a week she would go to customs to pick up the rare tomes that Cushing had ordered. Dr. Cushing’s chauffeur would drive her back and forth. A 1928 diary entry completes the image: “A relatively calm day. Gus took me down to the Customs House in the morning to get a couple of books from the Govt’s clutches. Another Helkiah Crooke and a Culpeper. The Chief seemed to think that they were rather expensive but the Crooke was much less so than the one he acquired last month.”

Madeline worked with Cushing from 1920 to 1933, when he retired from Harvard Medical School. Cushing, however, was not done quite yet. Taking a position in New Haven at Yale School of Medicine, Cushing was accompanied by Madeline in what would become her most engaging enterprise of her career. Dr. Cushing brought with him his extensive collection of books significant to the history of anatomy and surgery. Fulton was already at Yale as the Sterling Professor of Physiology, and his private library was even more extensive than Cushing’s. Taken together, these men through the work of Madeline Stanton had accumulated a vast and important private collection of the finest rare books on the subject of medicine ever assembled.

Madeline, through her work collecting and maintaining Cushing’s medical library, became the foremost authority on rare medical books and their whereabouts globally. Through her close relationships with some of the best physicians in the world, Madeline became a scholar. It was her depth of knowledge that extended beyond the titles and the catalog, quite literally into the content, that made her an exceptional expert. While at Yale, Madeline would have oversight of the books that Fulton collected as well.

Imagine the output of Cushing’s academic career of 13 books, 306 journal contributions, 328 papers, on top of teaching and actually performing thousands of surgeries. Now, imagine this against the backdrop of Madeline’s responsibilities to support this genius. It is easy to see how well matched these two individuals were. In fact, none other than Madeline Stanton prefaced a second edition of a Cushing book published in 1962. Madeline “played an incalculable part in Dr. Cushing’s life and work.”

At Yale Medical Library, Stanton served as the founding librarian of the historical collections for over three decades.

During the 1930s Dr. Cushing, Dr. Fulton, and Dr. Arnold C. Klebs of Nyon, Switzerland decided to donate their libraries together to the Yale University School of Medicine to form a historical library within the Yale Medical Library. In his will Dr. Cushing bequeathed his books to Yale, and in 1939 Madeline was appointed secretary of the historical library, which became housed in a wing of the new Yale Medical Library building, dedicated in 1941. In 1949 her title was changed to that of librarian of the historical collections, and on her retirement in 1968 she was appointed historical consultant.

Madeline Stanton’s life was dedicated to her work. There appears to be little to suggest any deep friendships or lovers. There was little opportunity for relaxation, play or vacations. By 1946, Madeline herself began collaborating to publish a catalogue on the history of anesthesia to mark the centennial of its introduction in the use during surgery. She would go on to become the world leading authority on the works of Michael Servetus, the 16th century Spanish physician and the first European to describe the function of pulmonary circulation. A census of known copies of Servetus’ works prepared by Madeline accompanied Dr. Fulton’s book on the subject published in 1953.

From 1948 to 1960 Madeline was assistant editor of the Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, and from 1961 to 1972 she was associate editor. During the quarter century of her tenure on the journal she established the highest of standards and exacting accuracy. In 1973 Smith College awarded her one of its highest honors in the form of an Alumnae Medal.

Madeline died in New Haven, Connecticut in 1980 and is buried at Canton Corner Cemetery alongside her father and mother. It was a life of labor, and little recognition. Cushing, in typical New England reserve, rarely acknowledged her work. A biographer observed, “It is possible that Dr. Cushing found the larger his debt, the less he could find words to acknowledge it.” Madeline for her part would glibly say, “Dr. Cushing had willed her to the historical library at Yale along with his books.”

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=34099