True Tales from Canton’s Past: A Jewel on Elm Street

By George T. Comeau

The Reed House on Elm Street as it looked when Nancy and Edward Mayo owned the house circa 1880 (Courtesy of the Canton Historical Society)

It is a small, unassuming house on Elm Street. Look closely and examine it from the street and you will see a low hip roof, an elegant yet simple porch, and a fanlight over the front door. This address, perhaps the finest and most sophisticated Italianate style house in Canton, is a national jewel beyond compare. The house helps to tell the international story of Tiffany & Co. in a way that connects Canton to the nation’s history and to global trade.

In 1845, Abigail French, a young widow from Canton, signed her name on the bottom of a deed for the sale of her property on what was then called Back Street. The property consisted of a house, 36 acres of land, and plenty of wood to service the estate. At the end of the deed the arrangement was made to reserve “the right of Abigail French to live in the house conveyed and occupy said part thereof as shall be necessary for her comfort and convenience and also to cut sufficient wood on said premises to support her fire, during her natural life.” The buyer readily agreed to the terms. The sale of the property was $1,000. The buyer was a young 28-year-old merchant from Boston named Gideon French Thayer Reed.

There was a private mortgage for the property and the deal was that Reed would pay the widow $550 with 6 percent interest over the course of a year. Written on a small slip of paper in Reed’s flowing script is a single sentence that describes the contract — an arrangement that today takes dozens of pages in a modern conveyance. On the back of the promise are the handwritten and signed records of the payments. By July 11, 1848, the property was fully owned and paid for by Reed.

Gideon Reed was born in 1817 in Surrey, New Hampshire. In 1839 he married Rebecca Jackson, and over the course of their marriage they had six children. Sadly, four of their children either died in infancy or before the age of 10. Reed was fairly well off, and his business interests were focused on the Boston jewelry firm of Lincoln, Reed & Co., located on the corner of Washington and Court streets.

As soon as he had fully paid for the land in Canton, Reed engaged a brilliant young architect by the name of Charles Edward Parker, a fellow native of New Hampshire who began his architectural practice in Boston about 1846. While nothing is known of his training before he arrived in Boston, between 1850 and 1852 he worked with architect Richard Bond. He was most active in the design of churches, public and institutional buildings, although his earliest known work is the house he built here in Canton for Reed. Parker would go on to design magnificent city halls, municipal buildings, and enormous granite structures in and around Boston. Parker’s works are significant and varied, and the house on Elm Street is particularly notable as one of his earliest works still in existence.

Reed would only get to spend small amounts of time in Canton. By 1850, only two years after his magnificent house was completed, he was in France establishing the overseas house of Tiffany, Reed & Co. at 79 Rue Richelieu in Paris. This was Tiffany’s first overseas branch and became invaluable to the company, as Reed — being a resident partner — was able to take advantage of the fluctuations in the foreign market and develop a large profitable trade in Paris.

Reed became fabulously wealthy, and he filled his Canton home with treasures and furnishings in the French style. Having an office in Paris enabled not only Tiffany & Reed Co. to access the widest selection of European goods; it also brought Reed himself into the best and highest of society from which he could emulate his own lifestyle.

Being an absentee from Canton had its perils. In 1865, James T. Sumner sent a letter to Reed’s brother-in-law, Edward Mayo, who was serving as Reed’s agent in Boston. Sumner wrote, “I hereby notify you as agent for Mr. Reed that I am going to have the line surveyed between Mr. Reed and myself next Saturday. You will please bring papers and I will do the same.” A property line dispute arose, and Mayo boarded a train from Boston to Canton to meet with the disgruntled neighbor. Arriving sometime before 8:30 a.m., Mayo went to the house on Elm Street. There, he waited, and waited. Mayo had lunch, and still Sumner failed to appear. Sometime after dinner Sumner arrived, accompanied by Augustus Gill, an MIT chemist, and Frederick Endicott, a prominent local surveyor. A few other folks also came to take stock of the property boundaries.

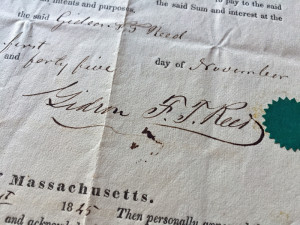

A detail of the original mortgage deed recently donated by descendants of the Mayo family to the Canton Historical Society (Courtesy of the Canton Historical Society)

Mayo reported back, “Deeds were shown by which Sumner claims a portion of the land embraced in deed held by G.F.T Reed Esq. After examination of deeds, and feeling satisfied that Mr. Reed’s deed was correct, I warned the parties present against any trespass on the property, stating that any person trespassing on Mr. Reed’s property would be held accountable. Mr. Gill informed me that he cut wood upon the premises last winter, supposing that he was the owner.” It is likely that neighborly relations were mended soon thereafter.

Reed was in Paris through at least the early 1870s. One of his daughters, Mary, died there in 1857. And passenger records show several transatlantic trips for both Mr. and Mrs. Reed. By 1872, while in Paris, Gideon Reed decided to sell his home in Canton to his older sister, Nancy. The deed was signed in Paris on November 12 and witnessed at the U.S. Consulate by none other than General John Meredith Read Jr. — a close friend to President Grant and a hero of the Civil War.

Nancy Reed and her husband, Edward R. Mayo, moved to Canton soon thereafter. They called their retreat “Pine Wood” and created a suburban botanical garden. Interestingly, the deed signed in Paris was delivered to the Dedham Registry of Deeds seven months after Reed and his wife had signed over the property. Mayo, for his part, was familiar with the property from his earlier dealings and the barn became his laboratory. It turns out that aside from his work as an agent, Mayo had been a bookkeeper at a large dry goods house in Boston. Mayo was one of, in not the oldest student of conchology in this country. For most of his life he studied and collected shells. In the halcyon days of the American clipper ships and whalers, Mayo was among the first to systematically purchase the shells brought as curiosities.

In the barn, to the rear of the house, Mayo stored his shells collected from fantastic voyages all around the world. Each shell was meticulously catalogued and a small slip of paper inserted in each to record the place from which they were collected. Almost 100 years later, a successor owner’s children gleefully played with the hundreds of shells, holding the giant conches up to their ears to hear the exotic oceans from around the world.

After the sale of the house to his sister, Reed began to become a wealthy benefactor to the arts and left Tiffany in 1875. When he died in Boston in 1892, he bequeathed millions to various charities. He was described as a “charming man, who would readily extol the attractions of Paris to his fellow Americans.” His philanthropy was quiet and unassuming, at one point donating $50,000 to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. After his retirement from Tiffany & Co., his son Alexander took up the role as European representative.

In 1929, Pine Wood changed hands again, and stayed in the family. Amy Mann, Nancy and Edward’s granddaughter, inherited the property from her uncles and she lived there seasonally until 1961. Purchased in the mid 1960s by Dr. Charles W. Vaughan, a noted otolaryngologist, he raised four boisterous children there, only selling it to move to Milton to make educational commuting to Milton Academy easier on the kids.

Interestingly, it was at this time that the wallpaper in the dining room of the house, furnished by Reed of the finest Parisian styling, was carefully removed and sent to Washington, D.C., to be used in the 1963 renovation of the Blair House. Jacqueline Kennedy served as a co-chair with Lady Bird Johnson over the Blair House Restoration Commission. Together these women oversaw the massive restoration and redecorating of our national treasure. The Blair House is the president’s guesthouse, and the wallpaper from Canton was destined for one of the grand rooms. The story told by Mrs. Vaughan is that there was not quite enough of the wallpaper for use as intended, and as such it was crafted into a drawing room divider and used as a decorative furniture element. Today Mrs. Vaughan recalls, “There was a bridge scene of sorts in the pattern.”

The story of the house at 35 Elm Street is indeed remarkable. The connection to Tiffany & Co., coupled with the fact that its wallpaper served as a national artifact, and that it was designed by one of America’s finest young architects in his day, make this a true jewel in our historic crown.

Special thanks to the Mann family, descendants of Gideon Reed. Also, thanks to the Vaughan family for assistance with additional details.

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=34175