True Tales: Lost Cursive

By George T. ComeauForty-five years ago I boarded a bus on Walpole Street and was dropped off at the Revere School on Chapman Street. The memory of that day burns vividly. I can recall the smell of crayons and paste, floor wax and ammonia, fresh air and sunlight flooding the room. We were a large class, by today’s standards anyway. There were 27 of us along with our teacher, Miss Patrone, all embarking on a new chapter in our lives.

The Revere School will always hold a special part in my life. It was the school that my mother had attended and it was quite simply the finest public school experience of that era. The school had four wings, arranged in a cross, with the center of the building forming a small assembly area. Each grade, one through four, had a single room. Lunch was trucked in, and milk was five cents. The basement served as space for movies and indoor recess. In the fair weather we all played outside on the property, never wandering past the chain-link fence.

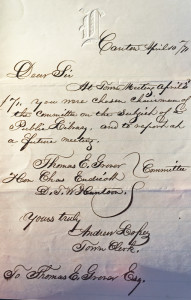

The Spencerian script of Andrew Lopez, town clerk in 1871, writing to Judge Grover and appointing him chairman of the committee on the subject of a public library (Collection of the Canton Historical Society)

The chalkboards would get washed down every day, and some of us would stay behind to help with the chores. Clapping the erasers was the best! There were plenty of days when we came home with our hair white and dusted full of chalk dust. The absolute first lessons were the basics of reading and writing. Above the chalkboards were cards with all the letters of the alphabet. We were taught the Palmer Method of penmanship.

The Palmer Method was developed in the late 1800s and published in 1894 in a book called Palmer’s Guide to Business Writing. We were being shown how to use “muscle motion” in our arms rather than simply to allow our fingers to move. Early educators also believed that the method would “increase discipline and character, and could even reform delinquents.” In the Revere School, the repetitious writing form was one that we all learned to master. In fact, we were graded on our penmanship as part of the overall assessment.

And so today, as a scholar and researcher, the ability to read cursive handwriting is a critical part of the work of a historian. There will come a day, and it is not too far off, when only a select few scholars will be able to access our past. Think about the last time you sat down and wrote a letter, a card perhaps, or even a short thank-you note. The art of handwriting is being lost to technology, and literacy is being transformed through the loss of cursive.

Cursive, the writing and reading of it, is in decline, as 21st century skills no longer require mastery over writing or reading handwriting. On visits to the Historical Society by children in the Kennedy School, each year brings a handful of students who puzzle at the antique handwriting and have a hard time deciphering the text. It is simply a fact that as schools focus on preparing for standardized tests, there are parts of the curriculum that get a shorter shrift.

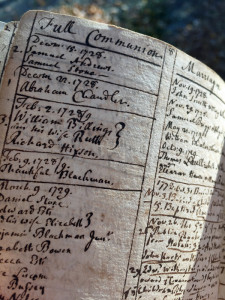

The ability to read cursive is an imperative in the work of historians. Indeed, there are several styles of handwriting in which Canton’s oldest documents are formed. The earliest forms of colonial “Round Hand” developed in the 1660s gave way to “Spencerian Script” in the 1850s — best exemplified by the Coca Cola logo as well as the script for the Ford Motor Company. The next style to arrive was the Palmer Method, only to be replaced by the Zaner-Bloser and D’Nealian methods. All of these styles are well represented at the local historical society, and the differences between them are stark.

In the Canton Historical Society the most prolific collection of documents in the holdings are those of D.T.V. Huntoon, a mid 19th century local historian, and the collections of the Draper family letters. The writing styles of many of our historical figures have become instantly recognizable owing to the close proximity of working with their letters over the past half century. The large books, manuscripts, deeds, and maps are all based in the various forms of colonial and postcolonial scripts.

Perhaps the greatest treasure is the handwriting of Parson Samuel Dunbar, our minister who kept a diary from 1727 to 1775. The writing is extremely tiny and written in iron gall ink — a formula that dates back to Pliny the Elder, who was born in 23 AD. It is here that even the most studious of scholars will have the most difficult time reading the script.

The early 18th century handwriting of Parson Samuel Dunbar (Collection of the Canton Historical Society)

And yet there are movements afoot to bring cursive into a new age. Many of the stories written in this column, if not all, begin with primary source material that has been scanned and is now available on the internet through online databases. Take, for instance, property and deeds. The originals are located in Dedham at the Norfolk County Registry of Deeds. In 2003, the registry began allowing the public access via the Internet to thousands upon thousands of records. Much of this record traces the history of land ownership to as early as 1793, the year that Governor John Hancock signed the legislation creating Norfolk County.

Less than 10 years after the founding of the county, Paul Revere purchased land in Canton. The deed, in highly descriptive flourishes of cursive, describes the boundaries along the Neponset River as including a small elm tree, an apple tree, and a heap of stones. To ensure that this deed, as well as countless others, are available for the next generation, Register of Deeds William O’Donnell has undertaken the ambitious task of transcribing all the deeds from 1793 to 1900. The cut-off date of 1900 is not arbitrary; rather it coincides with the acceptance of typewritten documents at the turn of the last century.

To understand the enormity of the task, the work involves 861 books containing an estimated 12.5 million lines of text. Earlier this year the registry had already transcribed over a quarter of a million deeds as part of a $2 million project. It took a team of 20 workers from Xerox to transcribe the ancient handwriting into typed documents. The project was funded through a state grant from a technology fund that is tied to registry fee revenues. And while the funding covered deeds, the future could be bright for mortgages and other documents critical to land use and ownership. Today, through the foresight of the registry, these records are online and available for all to read and use.

We sometimes forget that the documents that we hold most dear are those of our forefathers. And in this case, the Norfolk Registry is home to the land records of John Adams, Paul Revere, and even Horace Mann. One of the earliest records is from John Adams, second president of the United States, explaining how he wanted to build a school to honor John Hancock. The document describes Hancock as a great benefactor of the country and outlines some of Adams’ beliefs in the school system. This would become the same system that set out to teach the basics of reading and writing to tens of millions across the centuries, and to read the very documents that are the basis of our treasured history.

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=34814