True Tales from Canton’s Past: Keep Your Powder Dry

By George T. ComeauOn Pequitside Farm there is a wonderful hidden historic site that is worthy of note. Drive past the main house and follow the road until you get to the very rear of the property. As you walk past the community gardens, take a sharp turn to the right and start walking until you reach a lightly wooded knoll to your left. It is surmised by local historians that atop this flat piece of ledge stood the town’s first powder house.

Gunpowder was a necessity in the wilds of Dorchester as settlers began to move further from the central settlement of Boston proper and into a much more rural setting. Large animals, unsettled natives, and of course common criminals would all be a challenge in less populated parts of the colony. Unless the powder came from England, it was a difficult commodity to come by here in America. Since there were no known natural deposits of saltpeter, the critical ingredient, the colonists adopted a practice that was still in use in England to produce powder. The method required the collection of vegetable and animal manure containing nitrogen. Large quantities were collected into heaps in a shed or house where they were protected from the elements, and mixed with limestone, old mortar and ashes. The heaps were moistened from time to time with urine. When decomposition was complete, the heaps were leached with water, the liquor evaporated, and the saltpeter recrystallized. The process was long and labor intensive, and everyone was expected to participate.

Things changed drastically when in 1673 Reverend Oxenbridge, along with Reverend James Allen and Deacon Robert Sanderson, “entered into a partnership that savors more of things temporal than spiritual.” Their work in creating a powder mill on the Neponset River in what was the township of Milton was indeed successful and of this world. Two years later they took on a partner by the name of John Wiswall Sr., who by one historian’s account was perhaps “the first white man who ever lived in what is now the Town of Canton.”

The mill was situated just above the bridge that crosses the Neponset River in Milton and just on the Milton side of the river. A stone watch-house was erected on the opposite side of the river on what was Boston. The overseer of the operation was a man by the name of Walter Everendon (whose family is memorialized here with a street name off Walpole Street.) The mill did fairly well and was the first successful powder source in Massachusetts. We know that over time the Everendon family moved to Canton and their expertise in mills and powder production continued.

It was one thing to make the product and yet another to store and stockpile the valuable commodity. And, of course, danger was always an issue when dealing with wood-frame buildings heated with open fires, or damp weather destroying valued munitions. Having a suitable place that was safe, accessible, and secure became a challenge.

Before the Revolutionary War, the town kept a stock of powdered ammunition and placed it in the hands of individuals for safekeeping. Ancient town records show that in 1743 Major John Shepard was the custodian. Shepard was a fairly prominent man in our earliest history. He was a settler here even before Stoughton was incorporated in 1726. We know that he married Rebecca Fenno here in 1721, and that he was the builder of the tavern that would become known as the Doty Tavern when he sold his building in 1726 to Colonel Thomas Doty.

Shepard was so well thought of at the time of incorporation that he rose swiftly to every position that was available in local colonial government. Shepard was a member of the Board of Selectmen and served as chairman for four years. In addition, he was the town moderator for nine years. He held the title of “Squire,” which at the time was an honored symbol of respect. In 1746 Shepard became a commander of a military regiment. Between 1727 and 1754, he was named as the guardian of the Ponkapoag Indians — and here is where he got himself into some hot water.

In 1753 the town elected Shepard to be their representative to the Great and General Court, but by June the leadership of the House of Representatives expelled him. Apparently, after a visit to Stoughton the overseers of the Indians discovered that Shepard had “allowed his friends to cut wood on the Indians’ land, and that for five years his accounts had been kept in chalks and memory.” The people of Stoughton were quite upset that they had been denied their chosen leader, and the following year they voted to return Shepard to Boston as their representative. Without a second investigation, and quite quickly, he was expelled a second and final time. A special resolve was passed that stated, “Major John Shepard, of Stoughton, has behaved in his breach of trust as guardian of the Puncapoag Indians, and in his mall conduct as a Justice of the Peace, that he is unworthy of a seat in this house, and that the clerk of this house be directed to erase his name out of ye roll.”

Notwithstanding how the legislature viewed Shepard, the townspeople seemed to support and more importantly trust the man, so much so that he was placed in custody of the town’s entire supply of ammunition. It was a great responsibility and it generally fell to the best and most trusted military men in the community. A large amount of gunpowder was purchased for local use through a source in Boston. By 1745 three large chests were constructed by Preserved Lyon, a local builder, who incidentally had also built the town stocks.

Throughout the American Revolution Elijah Dunbar — arguably the “father of Canton” — was in charge of the local munitions supply. The son of the famous revolutionary minster, Dunbar was a Harvard graduate and among his accomplishments was the establishment of the first library. He also served as deacon of the church and was the man who petitioned to set off Canton from Stoughton. In short, the founder of our town if there ever was one was also in charge of our supply of gunpowder.

During the American Revolution one of the main powder mills for the Continental Army was located on what will soon become the Paul Revere Heritage Site. This was a major endeavor and a fortified military installation. It turned out to be the main reason that Paul Revere had knowledge of the water and mill privilege in Canton that he would purchase in 1801.

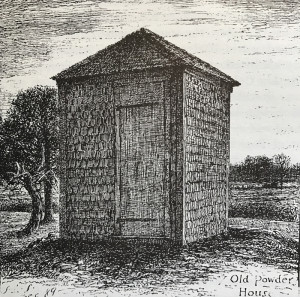

After the revolution, ammunition was kept in Dunbar’s “chaise house,” or garage, if you will. Finally, in 1807, the matter of actually building a powder house was brought before the town. As is the case now, and has been for over 200 years, a committee was formed to study the matter. In 1809, a powder house was built on what is now Pequitside Farm. The sides were built of stout plank covered with boards; it was shingled and crowned with a hip roof. The building measured seven feet square and seven feet high and was fastened to the rock with iron bolts. It stood on this rock until a new powder house was built on the town farm in 1858.

You can visit the site of the powder house today and see how remote it was to the rest of the town, and thus kept a safe distance from the danger of explosion. We have saved as artifacts a single hinge and three nails from the original structure, and they are in the collection of the Canton Historical Society.

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=35428