True Tales from Canton’s Past: Fresh Air and Sunshine

By George T. ComeauThe young boy leaned over the low windowsill and deviously spit upon his classmates below. The retribution at the hands of the principal was swift and decisive. The next memory that I have of the incident was crying in a janitor’s closet spitting into a slop sink until my mouth ran dry. The point was made at a very young age and it was a lesson learned at the edge of a windowsill at the Revere School on Chapman Street. Yet these were not just any windowsills. They were a technology that was conceived here in Canton.

The Revere School on Chapman Street was built to replace a much older building that was located at the corner of Neponset and Chapman streets. The conditions of the original two-story wood frame structure were dire. The building was built in 1827 at a cost of $600 and was originally known as Schoolhouse Number 6. In 1881 the building was named for Paul Revere and over the next several years the conditions deteriorated. A fire escape was added in 1912 to stave off fears of a disaster. That said, the superintendent of schools called the Revere deplorable: “The building continues to be unsanitary, without proper light and ventilation. It is now provided with a temporary fire escape but there is no place for the children to play except upon the street. We need a new building in a new location.”

Within a year the town brought forth Article 24 at annual town meeting and saw fit to appropriate money for a new school at a cost of $20,000. This was an opportunity to build a new modern building that would employ a state-of-the-art ventilation system so critical to combatting the rising tide of tuberculosis. Most wonderful was the fact that the technology that would be used at the new Revere School had already been tested for seven years at the Massachusetts Hospital School under the design and direction of Dr. John Euclid Fish.

Fish was an eminent physician and had come to Canton from Vermont and was the person credited with conceiving, designing and overseeing the “Hospital School for Crippled Children.” Fish was a strong proponent of the virtues of fresh air as a remedy for sickness. It was Fish who proved that foul air and smoke could be more quickly cleared from a room if buildings were designed in radically different ways. At the Hospital School, open classrooms would provide fresh air for “those suffering from the results of bone and joint tuberculosis and need the tonic of fresh air as an antidote to their tuberculous tendencies.”

Open air schools were part of a larger open-air school movement, which began in Europe with the creation of the Waldschule für kränkliche Kinder (translated: forest school for sickly children), near Berlin, in 1904. The movement quickly caught on throughout Europe and North America; construction of the buildings began in the first decade of the 20th century and carried on until the 1970s. The design and success already employed by Fish at the Hospital School campus on Randolph Street would be called upon by the Revere School Building Committee.

In adapting a healthier public-school design, Canton would be at the cutting edge in American school enterprise. The building committee wrote of their charge, “The responsibility of planning a school house that would, in the light of present-day knowledge, meet the requirements of the medical and teaching professions and promote the welfare of several generations of children was no easy task.” The new school would be designed by the architectural firm of Putnam and Cox. Among Putnam and Cox’s works were the Hotel Bellevue, the American Unitarian Association headquarters on Beacon Street, the Kirstein Business Branch of the Boston Public Library, Angell Memorial Animal Hospital, and a number of fraternity buildings at Amherst College and Mt. Holyoke College. It is quite likely that Augustus Hemenway, a wealthy Canton benefactor and chairman of the building committee, chose the architects. Hemenway donated all building and furnishing costs above the town appropriation. The real mastermind, however, was Fish.

The fear of acrid air in the days of rampant tuberculosis was real. Dr. Fish wrote that, “Exhaled air leaves the body at the temperature of about 97 degrees, with a strong natural tendency to rise until it becomes cooled to the temperature of the room, it can readily be seen that with no means of escape at the top it must become stagnant or to descend to the outlet. In its rise and fall it must of necessity become wildly diffuse with other gases and breathed as a mixture again and again.”

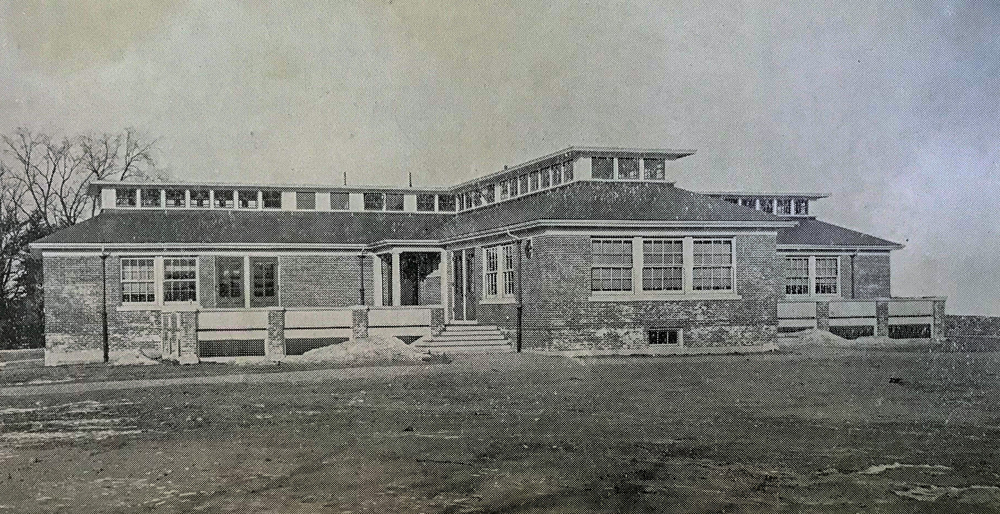

Fish designed a wholly unique and healthy building. Constructed in the shape of a cross, built of brick and with a slate roof, the school housed four classrooms and was designed for 144 pupils. Each classroom was equidistant from each other and the central core housed a gathering space and administration office. The outdoor spaces between classrooms were filled in by platforms, with doors that opened onto these spaces. Classes could be assembled either inside or outdoors for gymnastics, singing, folk dances, or such other exercises as the teacher may desire and weather conditions permitted.

The open-air concept was brought inside through an ingenious design that was a model around the world. The ceilings to the classrooms were sloped from the tops of the windows at an angle of 30 degrees into a monitor roof, on either side of which was a continuous line of windows hinged at the bottom and arranged to open outward. Worm gears opened the monitor windows and were operated by wheels in each classroom. In the winter, cold air came directly through the open windows and was warmed by being passed over low-pressure steam pipes under the windows. As warm air passed into the room, it would rush upwards and escape through the monitor high above the classroom.

Another innovation at the Revere School was the design that all three walls exposed to the outside had banks of windows and when combined with the glass monitor above, the classrooms were flooded by natural light. The building committee praised the fact that “nature’s great disinfectants, fresh air and sunlight, find easy access.”

The new school opened on November 24, 1914, and the response was phenomenal. Word of the innovative design spread around the globe. At first, entourages made up of school committees from all the major cities and towns came to see the building. Within four years of opening, the tours took on a more international flair. Educators from Paris came calling, followed by a contingency from New Zealand and then Belgium. This small school became a model for the open-air classroom concept and the innovations were copied in countless other locations.

It was my first school, and one that I have vivid memories of. Aside from the “spitting incident,” it was my job to turn the transom wheels above Mrs. Mary Ronan’s classroom. Each Friday, Barry Kelly and I would clap the erasers outside, and then arrive home like goofy French mimes covered in chalk dust. The windows were always open, and that very first day of school, when I arrived in first grade, the room was flooded with sunlight. It was a warm and welcoming place that is seared in memories of countless children who passed their time in clean fresh air.

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=39203