True Tales from Canton’s Past: Ox & Rail

By George T. Comeau

In the Cushman family photos is this image of sturdy oxen with Blue Hill in the background circa 1890. (Courtesy of the Canton Historical Society)

Canton smells different today. We take advantage of clean air and fresh water and expect it as a given. As you can well imagine the Canton of the mid 1800s was a far different place than the world we know today. It is likely that you can count on one hand the number of pigs that can be found in our boundaries — Vito, yes that is you! And as for cows, we gaze onto the bucolic bovine that sometimes find a home at the Bradley Estate. Sheep, yes there were a few on that small farm on Pleasant Street, but they too have dwindled. As for oxen, not a single head can be found in Canton today.

In the mid 1800s we enjoyed an uncommon array of livestock tied to the manufacturing of goods. There were 14 sheep dedicated to producing about 50 pounds of wool, 261 horses used in manufacturing and commercial transportation, and 406 milk cows along with 72 heifers used to produce more than 10,000 pounds of butter and another 2,400 pounds of cheese. More than 141 acres of land was used for Indian corn, another 117 acres for potatoes, and we grew barley, rye, onions, turnips and carrots in very large quantities. Surprisingly, we dedicated close to 100 acres of land exclusively for cranberry bogs — an area about the size of downtown Boston. As for fruit trees, the town was dotted with orchards that held 3,100 apple trees and 631 pear trees. And yet, in factories it was the oxen that took second place behind the water rights powering the mills.

It was the ox that powered the factories at the Revere & Son Rolling Mill and the Kinsley Iron Works. Each plant accounted for almost 50 men, and the material could weigh many tons. The mighty ox was used to move those finished materials in great quantity along the tracks to be transferred to waiting railroad cars at Canton Junction. Combined, both factories likely accounted for several of the 51 oxen in town with a value of $2,875. Adjusted for inflation, that value would be approximately $85,000 today. Yet the value to these large mills was defined by their output and ability to send 700 tons of bar iron from Kinsley and 1,000 tons of copper to customers all across the country. The oxen were the key to making the railroad work for these businesses.

The barn that has been preserved at the Paul Revere Heritage Site was most likely expressly built around 1845 by Joseph Warren Revere as part of a major expansion at the mill. In 1909, as the mill complex went to the auction block, it was described as a “splendid stable.” And by 1909, it likely housed a few remaining horses that would be used as folks transitioned from animals to the automobile. There are photos of horses on the property, yet the barn is so much larger than would have been needed for horses alone. Most likely it was built for oxen.

Barns built for industrial uses are rare finds in New England, largely because fires were so frequent. Ash from the smokestacks could find easy fuel in the hayloft in these enormous wooden buildings. It is a small miracle that the barn at the Paul Revere Heritage site survived through the past 173 years. There were major fires that threatened the building several times over the past century, and yet it survived. When it was moved recently, large quantities of hay filtered down through the timber-framed walls. It smelled of manure and punky wood and there were the vestiges of an old stairway that had been worn to a turn by thousands upon thousands of boot heels and now subsequently lost to the renovation. Fragments of horseshoes and nails found their way down to the basement as the barn was salvaged and moved to the new location.

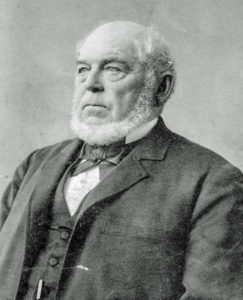

Captain Charles Franklin Cushman was the inside foreman of the Kinsley Iron & Machine Co. (Courtesy of the Canton Historical Society)

Recently, the estate of Frances and Theodore (Ted) Clines donated a small parcel of materials in a cigar box that Ted had purchased at a yard sale in 1966. Inside the box were perhaps 40 glass slides. Images of oxen, horses and cows. Images of a house long lost on Washington Street. The gold capped cane, and the silver spoon. There were a few pages of militia records, and a daguerreotype. All this material was tied to one man: Charles Franklin Cushman.

It would take some sleuthing, but soon the pages of time slipped away and the story became more complete. Cushman was born in North Rochester, Massachusetts, in 1817. At the age of 17 he shipped from New Bedford on a whaling vessel and spent 12 years at sea. Upon his return, he started work at an iron concern called Tremont Mills in Wareham. At age 26 he married Hope Cobb Clark and they had two children. By 1852, Cushman’s second child was born in Canton and he was employed in the Kinsley Iron and Machine Works on Washington Street. We get a unique view of Cushman’s life through some interesting artifacts, papers and photographs that are only now being uncovered. And through this small trove, we see the life of the animal and the factory man intertwined.

Cushman was a captain in the Union light infantry, a volunteer militia group. He was referred to as Captain Cushman. Many of the names listed on his militia roll are men from the Kinsley Iron Works. The gold-tipped cane that has been recently donated is engraved 1865 and was a gift from the employees of Kinsley Iron and Machine Co. where he was the foreman. This may have been his retirement gift. The glass plates show a family life at the corner of Washington and Sherman streets and includes vacation photos from the ancestral home off the shores of Plymouth. We see the family pets, the children at play, a rare glimpse inside the dining room at mealtime. There is a silver spoon that is marked by the firm Lincoln & Foss and was awarded to Cushman for his marksmanship during his militia days. Taken as a whole, this small collection helps illuminate the life of the factory manager who lived comfortably within walking distance of the factory.

What stands out in the glass slides and pictures are the wide array of animals that are the subject of the photographs. Perhaps the most wonderful of these is the pair of oxen that are being led by a small boy through a pasture with the Blue Hill in the distance. The boy, no more than 7 or 8, is likely Captain Cushman’s grandson and namesake Charles Cushman, who would grow up to be the local milk dealer. By the time this young man was an adult the oxen were pretty much gone as well as the factories that had depended upon them. It was the end of an era.

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=41686