True Tales from Canton’s Past: The Epidemic Rages

By George T. ComeauPerhaps we take our modern town for granted. We are blessed with clean water, air and septic systems that keep us safe and healthy. Our Board of Health is an amazing asset to our community. Organizing health fairs, inspecting restaurants, working closely with school nurses, and overseeing extensive licensing and permitting are all responsibilities of the this elected three-person board. The work they do is quiet and in the background, and we are kept safe and healthy in ways both big and small.

An 1891 pamphlet that extolled the virtues of a healthy Canton, promoted by a local real estate agent (Collection of the Canton Historical Society)

The modern Board of Health traces its genesis to the late 1800s when toxic fumes and rancid water mingled with industrial and animal wastes to create epidemics that swept through the town with alarming stealth and deadly consequences. Open water bred contamination and sewerage mixed into the water supply in ways that created widespread problems throughout the densely populated immigrant neighborhoods of downtown Canton. A milk supply was so thoroughly contaminated that 400 people fell seriously ill and 20 deaths occurred at a time when penicillin would have cured the masses. It was something as simple as strep throat that brought deadly consequences. It was the Board of Health that was on the front lines of easing the outbreak and restoring health to the town.

In 1893, the board submitted its annual report. Reading between the lines, it was a painful year. “We will omit much of the agony we have endured, and state only that which is of value,” they wrote. “We can frankly and honestly say that for all the criticism we have received, their rankles not within our bosoms one unkind thought to a living soul. We have done our duty as we have seen it, without fear or favor, we have not worked for re-election but for common good.” These words are wonderful and self-effacing in so many ways, and provide some insight into the character of these men.

There were myriad challenges that faced those early boards, and minimal tools to meet those challenges. The yearly reports read like a Dickensian novel rife with diseases that have long been quelled. Spring and summer were seasons filled with cholera and winter was met by “La Grippe,” what became known as Spanish Flu and would take almost 100 million lives across the globe. Typhoid and diphtheria were also rampant and the Board of Health was tasked with managing all and working to keep epidemics in check. This was no easy task, and they were constantly faulted at every turn.

On January 12, 1893, in a small house on Mechanic Street, a child came down with a very high fever. A red rash appeared and soon a doctor attended. In the throes of delusion and pain, this child became the first reported case of scarlet fever and the Board of Health was notified. Soon, the entire family was infected and by February the sickness had spread to Bolivar Street. In March of that year 21 children had fallen sick and the sickness raged on. Street by street the disease raged — from Mechanic to Bolivar then onto Rockland and North, soon to Pond and Pleasant and then into Walnut, High, Dedham, Washington, Sherman and Prospect. Deaths followed in alarming numbers and out of proportion with the illness — four in one month and six more in the next. By March, the epidemic “assumed grave proportions” as the Board of Health worked to stop the sickness from infecting new streets. “Still it kept reaching out and getting on to new streets. The people became alarmed and from all quarters the Board of Health was being condemned for not closing the schools, parents fast begin taking their children out until they were not scholars enough left in some of the schools to form a corporal’s guard.”

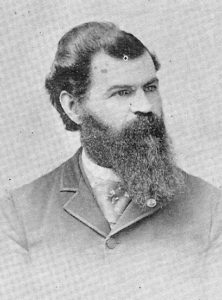

Dr. George Iverson Ross was Canton’s local physician and was instrumental in forming the early Board of Health. (Photo courtesy of the Canton Historical Society)

The deaths kept coming, and when it came to dealing with the parents of these sick children the board was forced to “look into their faces and read the language of the heart, their little ones in danger, their very soul seemed to speak to us in a language unheard, yet which touched the inner heart.”

In April, after 10 weeks of a raging epidemic, the board responded to the pleadings of the grief-stricken families and ordered the schools closed. This was met in some quarters as wholly unreasonable, mostly by citizens without small children, who felt that the science and statistics worked against closing the schools. The point was moot since most families decided to keep their children home as a result of such great fear from contagion.

The schools were closed for all of April and indeed the epidemic “assumed a milder form,” and so by May 1 the board allowed them to reopen, with the caveat that all children from infected homes would stay out of school for the remainder of the year. The rift between the School Committee and the Board of Health widened, as the people in charge of the schools questioned the judgement of the health agents. The issue turned on whether a perfectly recovered child from a previously infected household could return to their lessons. The Board of Health turned to S.W. Abbott, the Massachusetts secretary of health. Abbott felt that since the epidemic had abated, the children recovered, and the houses thoroughly disinfected — then the children could all go back to school. Given this advice, most of the scholars were allowed to go back to their desks.

In the days before modern antibiotics the cure was palliative at best. Complete isolation was the usual course of treatment for both the patient and anyone nursing the health of the sick. After the sickness abated, the complete disinfecting of the house was required. Carpets, furniture, window hangings and all objects — especially wooden —would be removed or destroyed by burning. Cloth used for tending to the ill was burned and mouthwash of chlorinated soda and permanganate of soda was employed in both the sick and healthy. Carbolic acid was added to the “slop” from the bathing and washing. The advice given to the sick families was extensive and in many cases ineffective, yet all that could be done to slow the infections was employed as quickly as possible.

At the time, the Board of Health was looked upon with disdain and called “ignorant officials” by the people of Canton. The board countered by pleading guilty and asking for mercy. It is so hard to imagine. The board itself wrote many times that they were “painfully aware of the fact that the office is looked upon by many as an office requiring no thought and no special knowledge.” The early boards were looked upon as “a needless expenditure of public funds.” This opinion would take many years to change, largely as a result of the acceptance of science and the advances of treatment which would create a knowledgebase to draw upon.

As the scarlet fever epidemic abated in the early summer months, the board wrote to the citizens, “We assure the public that we have not been unmindful of the trust confided in us. We have done our duty fearlessly, honestly and with as much capability as our limited capacity would allow. We will carry with us to private life a kind regard to all friends … To our friends ‘the enemy,’ we are as ready to forgive as they are to be forgiven.”

In the end 73 children and adults fell ill and 15 died in the course of the local epidemic, which lasted more than seven months and raged across a dozen neighborhoods.

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=62550