True Tales: Setting the Scene for Murder

By George T. ComeauThe following is the first in a two-part series. Click here for part two of the series.

At age 55, Sarah Ellis was a sturdy woman who had endured the loss of her husband just two years prior. At the hands of a weak heart, Daniel Christian Freleigh Ellis’ death had saddened the community. This was a family that was well known in Canton, and as the head of the household, Daniel Ellis was responsible for the care and support of his children. When he died, Sarah would have to take on a large burden — that of raising a boisterous teenage boy.

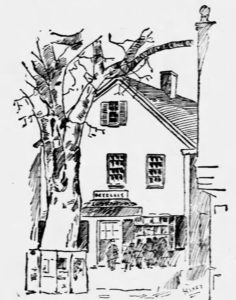

Daniel C. F. Ellis, local shopkeeper and member of the Blue Hill Masonic Lodge (Courtesy of the Canton Historical Society)

Daniel C.F. Ellis had lived in Canton for much of his life and was a prominent shopkeeper. Born in Crawford, New York, in 1827, his mother died a month after he was born. By age 23 he had settled in Canton and was a machinist in one of the local mills. Saving his money enabled him to marry, and in 1854 he purchased the property at 541 Washington Street. The building still stands today and is locally known as “Matt Kelly’s.” Few people would know that it is one of the earliest surviving commercial buildings in Canton Center. Built in 1843, for the past 177 years it has been a commercial property with a dark secret.

In 1855, Ellis began a trade store and soon thereafter ran a saloon. As the temperance movement heated up he started a drugstore and then became a news dealer. In 1864, Ellis joined the Blue Hill Masonic Lodge and enjoyed great respect from his fellow brothers. This was a very well regarded man that produced a large family as a result of two marriages that yielded at least eight children.

When Ellis died, the shop in Canton Center was left to his wife, and she continued to live above the storefront on the second floor and sold newspapers and sundry items. Two servants named Grace and Sally Thomas boarded alongside Annie and her brother Everett. The boy, Everett Alton Ellis, was only 13 when his father died. Everett attended Canton Public Schools, but as he got older things got harder. Before his father had died, he had been enrolled in the most prestigious private school in Boston — the Chauncy Hall & Berkeley School. After his father’s death, the situation changed dramatically.

Without a father figure, the boy was a handful and was considered to be quite wild. In particular, Everett loved guns and could be seen boasting to his friends his ability to be an expert shot. Many times it was reported that he would twirl a revolver in his hands “wild west” style. At one point the boy had shot out the window of Reilly’s Tailor Shop and his mother had to make restitution. Handling Everett became a task that became burdensome for his mother, and in April 1893 she decided to send the boy to live with his uncle, Dr. Willard Everett, in Hyde Park. With a new “father figure,” it was expected that Everett would have a stronger direction. In fact, Dr. Everett immediately enrolled the boy in the Grew School to bring some semblance of discipline to his education.

Once Everett was gone to live away from Canton, Mrs. Ellis turned to an affable young man named John Fleming to assist in managing the store. At 18, Fleming was well known and the oldest of a family of five children living on Mechanic Street. Fleming’s father worked in the Kinsley Iron Works rolling mill, having come from Taunton to Canton in 1894. Fleming was noted as a “bright little fellow, very reliable and diligent.” Each day, early in the morning, Fleming would sell papers at Canton Junction and in the summer would sell them onboard the trains between Boston, Taunton and Brockton. Most of the day would be spent at school or tending the store for Mrs. Ellis. At age 6, Fleming was injured in a sledding accident that left him quite disabled. What was most memorable for locals and the riders of the train was that Fleming was a “hunchback” and his winning personality overcame his disability.

It would appear that both boys would have a bright future. In one case, the Ellis boy was quite privileged, and in the other case the Fleming boy was building a future through hard work and a winning character. Alas, this was not to be realized. On the morning of Saturday, February 16, 1895, one life would ebb away and another would be burdened by allegations of a dark and sinister murder.

Rumor and innuendo swirled around the exact details of the incident, but many facts have emerged 125 years later. Through a review of an inquest that was conducted in Dedham, testimony of eyewitnesses and stories by reporters that covered both the aftermath and the subsequent trial, we can get a sense of the sadness and anger surrounding the event that transpired in Canton that day. It would take over a year for justice to be administered and the truth was complex and elusive, compounded by the lies of the young perpetrator.

On the weekend of February 15, 1895, Everett Ellis was back in Canton, having left Hyde Park on the 4:30 p.m. train to town. In his pocket was a revolver that he had purchased for about $2 and in the other pocket he had 20 bullets. Ellis spent most of his weekends with his mother and sister in the small apartment above the store on Washington Street. On that fateful Saturday morning, Mrs. Ellis arose early to attend to business in Boston. Leaving her son and daughter and a servant girl, she walked to the train without any inkling that her world would change. Everett Ellis awoke after 8:30 a.m. and went downstairs to the store to read the paper. In the downstairs shop he found Fleming and Harry Thomas, a 14-year-old friend of Fleming. Ellis discovered that the water pipes had frozen in the basement of the store. Gathering some old newspapers, he headed to the basement to thaw the pipes by setting the paper on fire and running the flame under the pipe.

Soon, another boy arrived by the name of Johnnie Powell and the boys began discussing how marvelous the weather was for sledding. Fleming took the opportunity to head to his house — about a 10-minute walk away. Mrs. Ellis did not like to leave the store unattended, but Fleming had to bring cough medicine home to an ailing brother. As Fleming was leaving the shop, Powell asked to borrow a sled, and Fleming replied, “What will you give me to borrow my sled?” and Powell simply laughed. Ellis volunteered his “double runner,” which was in the back room of the store. Once alone in the back of the store, Ellis showed the revolver to Powell. Soon after, Fleming arrived back and Ellis showed the revolver to him.

“I’ll sell the gun to you,” said Ellis, and Fleming replied that he would “have no use for it” and that he’d be “afraid he would get hurt with it.” Ellis pushed the deal further and offered the gun for $2 payable in 25-cent installments per week. Soon, Annie Ellis came downstairs carrying a warm winter coat for her brother. The plan was for her to go to the nearby stable and hitch a team of horses so that they could go coasting on a sleigh.

At that point, after Annie left, the store was empty with the exception of Ellis and Fleming. There are conflicting statements made about what happened next. What the reader needs to know is that before noontime, one boy lay dying with a fatal wound through his head and the other boy had fled the scene. Within minutes of the shooting, the rumors caught fire through the town of Canton like no other. The Canton Journal wrote that, “It is difficult to see how intelligent men with the facts all before them, could get them so misplaced. Mrs. Ellis’ good standing and the universal respect in which she is held in the community are well-known. In spite of all sorts of bloodthirsty rumors about town no one who has studied the case at all has any idea that there was malice in the shooting.”

As the cast iron stove in the center of the store began to cool, the room became flooded with doctors and police as well as helpful bystanders. And the search began for the boy with blood on his hands and fear in his heart. He would be labeled an attempted murderer and what was to become of his dying friend?

Click here to continue to part two.

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=64133