True Tales from Canton’s Past: Mama, I’m Cold

By George T. ComeauThe following is the second in a two-part series. Click here to read part one.

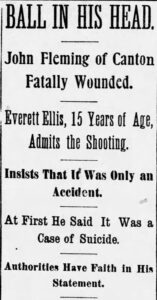

Perhaps they weren’t quite friends; they certainly were well acquainted. Everett Ellis was only 15 years old and had been in trouble before. In most instances, Ellis’ mother was able to buy him out of trouble. There was an incident when the boy had been shooting through windows and his mother had to pay restitution to keep the boy safe from any police action. But now, as he looked at the gun in his hand and glanced up and saw the gaping hole above the left eye of John Fleming, Ellis panicked.

Rushing upstairs, he gathered a small bottle of whisky, some rags and a hot wet cloth. Turning to the domestic servant, he exclaimed that Fleming had “shot himself and that she had better not go downstairs.” Grace Thomas looked at him with disbelief and said that “someone needed to go and help the boy.” Pushing Ellis out of the way, she went into the backroom to see Fleming lying there “with blood trickling from a gaping wound in his head.” The girl was overcome and fled back upstairs. Ellis then started to clean the wound and poured whisky into the victim’s mouth, which in turn ran out of his nose in a gurgle and a sneeze. The gun — what to do with the gun? Ellis decided in a panic to perfect the story of a suicide attempt, placing the gun in the pants pocket of the dying boy. On the floor lay a pool of blood and Fleming’s hat.

And at that point, Annie Ellis, Everett’s sister, came back from the stables and saw the terrible sight. Annie knew the condition was dire, and together, the two siblings went nearby and called for the doctors. At the time there were three doctors in Canton, and all had offices quite nearby and none were in their offices. But shortly after and via telephone Doctor Lonergan was summoned.

Lonergan had been in Canton for nine years and was well respected. Entering the back room of the store, he saw Ellis and was told by him that “Johnny had fallen down the cellar and hurt himself.” Ellis explained to the doctor that he had carried the small boy up the stairs and washed the wound. Lonergan thought at that point that Fleming may have had an epileptic fit and sent for the boy’s parents. Within moments, Lonergan found the bullet wound.

At that point a second doctor arrived by the name of Steadman. With 20 years in the practice but only a few months in Canton, Steadman was careful to make a thorough exam and also noted the wound above the boy’s eye. Turning to Ellis, Steadman asked, “Where is the pistol?” To which Ellis replied, “I don’t know.” In fact, Ellis knew quite well — it was in the dying boy’s pocket — exactly where he had placed it. He told Steadman to look into the boy’s trousers. Steadman found a .32 caliber self-cocking revolver with five chambers, four loaded and one empty. It was becoming clear that this was not an attempted suicide. Shooting oneself in the head and then being able to place the gun inside a pocket is impossible. The story was not adding up, and Ellis slipped from the room.

The rest of the morning was a blur, as crowds gathered and the police came. Soon, Fleming’s mother and father arrived and they saw their child in distress. In fact, Ellis himself had run to the Fleming house to summon the mother. Ellis looked at Mrs. Fleming and said, “Johnnie shot himself,” to which Mrs. Fleming replied, “No, he was just here.” Within moments the gravity of the news struck the dear mother and she cried, “My God, he’s done.” Ellis took the frightened mother by carriage to the store. In the back room she saw her son surrounded by doctors.

Several injections of both atropine and brandy were being administered to keep the boy alive. The doctors began probing the wound to a depth of five inches in a futile attempt to find the bullet — lodged at the base of the brain. The boy would arouse from an unconscious state and both the police and his mother would ask him questions, but he would merely nod and say his neck hurt. Looking into his mother’s eyes he muttered, “Mama, I’m cold.” A third doctor by the name of Ross arrived and he also began an examination. At some point he turned to Mrs. Fleming and told her to send for a priest. The scene inside that small back room was devastating to behold.

By midafternoon the Boston Globe had the story and sent a reporter on the train to Canton. At 1 p.m. Fleming, still in the back of the store, began to gain consciousness again. Being questioned by the doctors, he could only nod yes or no. Fleming nodded “no” when asked if he shot himself. The physicians all conferred and it was decided to wrap the boy in blankets and place him in a low sleigh to be brought home under the guidance of Officer Plunkett of the Canton Police. A bed was made up for him in the house on Mechanic Street and he lay there in distress and convulsing as his blood pressure and body temperature slowly dropped.

Meanwhile, Ellis had slipped into the crowds of bystanders and was soon sent to the upstairs parlor of his house, where he ate lunch and chatted with the Boston Globe reporter. The reporter knew many of the lies that had been told by the 15 year old. Where the local constabulary had shown great restraint in questioning, instead the reporter went straight to the facts. “The boy seemed pretty badly shaken up by the categorical inquiries.” It was Annie Ellis who put an end to the questioning and took her brother to a room at the back of the house.

By 4 p.m., unaware of the situation in Canton, Mrs. Ellis boarded a train to return home. At that same time, almost five hours after the shooting, Officer Plunkett returned to Ellis’ home and again questioned the boy. “I’ve come back because I learned that you had a revolver,” explained Plunkett. Ellis looked at the policeman and asked, “How did you know?” to which Plunkett replied, “Harry Thomas told me, and now you might as well tell the truth.” And, in tears, the boy told him exactly what happened: “I showed the revolver to Johnnie, and passed it back and forth, and when it was in my hands it went off.”

Officer Plunkett placed the boy under arrest while his sister was in the front parlor of the house. Together Plunket and Ellis walked to the lockup, nicknamed “the cooler,” which at the time was in the basement of the fire station on Bolivar Street. Soon, Mrs. Ellis arrived back in Canton to learn that her employee was dying in his bed at home and her son was in jail.

A view of the newspaper store circa 1920, now the site of Matt Kelly’s Pub. (Courtesy of the Canton Historical Society)

By the end of the day, the police were convinced that there was no malice and wanted to call the whole affair an unfortunate accident. Fleming, the “trusty, hardworking lad,” was suffering at his home, and Ellis, the troubled youth, was behind bars. At 10 p.m. that evening, Officer Patrick Kelley went to the Ellis house and picked up a change of clothes from the boy’s mother. Upon tendering them to Ellis in his cell, Kelley told the boy he would get imprisonment for life. As the night wore on, in the quiet of the jail cell, Ellis cried himself to sleep. And at the Fleming home, the lights burned late into the night and on into the Sunday morning dawn.

As the sun rose, John Fleming’s breathing became shallow and raspy. Father and mother and siblings nearby, they tried to bring the boy some comfort. At five minutes before seven the boy drew his last breath and died. Church bells rang through town as morning services began to get underway. On Sunday, the day that John Fleming died, Reverend Henry Fitch Jenks preached a sermon at the Unitarian Church. The town was just coming to grips with the tragedy. Looking to his faith, Jenks spoke softly and referenced the fourth verse of the fifth chapter of Matthew: “Blessed are they that mourn, for they shall be comforted.”

The following day an inquest was held in Stoughton District Court and the courtroom was cleared of the enormous audience that had come to see the Ellis boy brought to justice. More than 20 witnesses attended and the inquest took much of the day. At the end of the afternoon, Everett Ellis paid a $1,000 bond and was whisked away by his uncle to Hyde Park to await trial. Throngs of people went to the train station to see the accused killer. A week later the bond was increased to $2,000 and that too was paid and the boy stayed released prior to trial.

Fifty-nine days after the shooting, the trial began in Dedham. It’s worth reciting the opening paragraph of the Canton Journal on April 19, 1895: “Damp and chilly Easter Monday dawned. Old Dedham is drear and forbidding these chilly spring days before the leaves break out on her towering elms and graceful maples. The light gray mass of the stately court house rises majestically, well-nigh covering the plot set apart for its occupancy. And here in the only partly finished building, prodigal in its promise of future accommodations, the one case in which above all others Canton is interested in was called at 10:30 Monday morning.”

The trial took two days and was widely covered. Ellis “entered the courtroom and appeared cool and collected and took his seat at the left of the cage. His uncle, Dr. W.S. Everett of Hyde Park, accompanied him.” The jury was made up of a hotel keeper, a farmer, a shoemaker, and a fish dealer, among other common men from the surrounding towns. Horace Guild of Canton was excused as a juror at his own request. During the trial the participants were struck by the lack of emotion and indifference of the accused.

The charge was manslaughter and the trial took two days, and several witnesses testified, including Ellis himself. Within an hour the jury returned a verdict of guilty. The next phase of sentencing was more complicated. The judge felt that although the boy seemed indifferent at trial, he did not feel that a prison sentence would be particularly helpful and thought that placing the boy on probation would be a more kindly act. In effect, it was a sentence of “go and sin no more,” as the prosecutor called it, and he respectfully disagreed. The sentencing portion was continued into the following year, and it is unlikely that Ellis ever spent time in prison.

True justice was never delivered, and the town of less than 5,000 residents remained stunned and saddened by the events that transpired inside that small store. Mrs. Ellis went on to maintain the store, but she would eventually move to Stoughton to live with her daughter and her son in-law. Everett Ellis lived a full life, moved to New York and held various jobs, and died sometime in the mid 1950s. The scene of the crime is still an active business in the center of town.

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=64318