True Tales from Canton’s Past: Lines in Memory

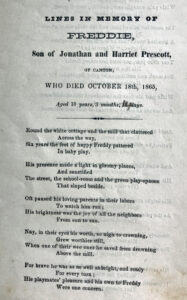

By George T. ComeauEvery so often a mystery begins simply with a question, a curiosity. So it is no surprise that recently when a slip of paper fell from the leaves of a donated book, a flurry of questions would ensue. At the top of the paper was printed “Lines in Memory of Freddie.” What followed was a poem that documented the all too short life of Freddie Prescott and his 10 years here in Canton that ended on October 18, 1865. So many questions, and so few answers. Yet each stanza of the poem unlocked a view of Canton in the mid 19th century.

As was so often the case in the mid 1800s, this was a very close-knit community. Everyone knew everyone else. For many, they had one foot firmly planted in the fields and the other in the factory. The center of industry was focused on what is now Canton Center. Largely from Bolivar Street to Revere Street you’d find large, filthy and noisy factories. The big players at the time were undoubtedly the Revere & Son Copper Company, Kinsley Iron Works and the Ames Manufacturing Company. All three companies were somewhat symbiotic and required skilled and unskilled labor to meet the rising needs of a nation in the throes of an industrial revolution coupled with the expansion of the transportation system.

Freddie’s father, Jonathan Prescott, was born in 1819 in Rome, Maine. Rome was described as a “beautiful farming town” with a “pleasant and flourishing village” — a bucolic, rural life. Meanwhile, about 200 miles south, Canton was bustling with factories, farmland, strong schools, and opportunity to own a house and perhaps a cow in the backyard. Without a doubt, one of the things that made Canton so attractive was that there was work to be had at a fair wage in decent, yet dangerous factory jobs.

The Prescott family has an impressive pedigree, with a lineage that can be traced to Sir Richard de Prestcote — born in 1150 in what is now England. The family came to North America in 1665 and settled in Old Norfolk County, which was one of the four original counties of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and consisted of settlements north of the Merrimack River (including parts of present-day New Hampshire).

In the colonies, the Prescott family achieved distinction with great-grandfather Jonathan Prescott serving in the American Revolution. And even more notable was the fact that Jonathan Prescott’s maternal great-grandfather was John Rogers, who served six years in the Continental Army under General Washington and witnessed the surrender of Cornwallis.

In 1854 Prescott came to Canton and took a job with the Ames Manufacturing Company. With the strong and impressive lineage it is no surprise that he came into the trust of the Ames family, who had successful manufacturing concerns across the region. The company manufactured shovels, and the strong demand would continue through the mid 19th century concurrent with the great expansion of railroads and later the American Civil War. Abraham Lincoln personally asked Oakes Ames to supply shovels to the Union Army. This made the Ames brothers very wealthy men and also very generous. The Ames brothers entered politics and became influential in financing the construction of the Union Pacific Railroad, as well as the development of the village of North Easton. Prescott was in charge of the shovel departments at North Easton, Bridgewater and Canton and worked for the company for 46 years.

In 1850, Prescott lived in Easton with his wife, Harriet, and they welcomed their first child, Ellen, into the world. After moving back to Maine, Prescott was summoned to Canton and lived on Bolivar Street. In 1855, Freddie was born to the family, and in 1858 the family moved into a brand-new house with a barn on a hill on the south side of Bolivar Street. The house was located across from the shovel shop where Jonathan worked and he purchased the home for $1,350 — a large sum of money in those days.

Here is where we begin to glean more about the short life of Freddie and where the poem gives us a glimpse into this family. “Round the white cottage and the mill that clattered across the way, six years the feet of happy Freddy pattered in baby play. His presence made a light in gloomy places, and sanctified the street, the school-house and the green play spaces that sloped beside. Oft paused his loving parents in their labors to watch him run; his brightness was the joy of all neighbors from sun to sun.”

The poem goes further and describes an event that may have surely established Freddie as a hero in the town, when the poem describes the affection the townspeople had for this boy. “Nay, in their eyes his worth, so nigh to crowning, grew worthier still, when one of their wee ones he saved from drowning above the mill.” Drownings were so common in these times and with the abundance of water powering the mills, it was a frequent cause of death. Freddie saving a friend from certain fatality would have established him as a fine hero of his day.

But, sadly, the poem turns to a darker place as it describes either an accident or a disease that struck the boy: “So when he caught the fall that helpless laid him with withering bone, you would have thought (such care the neighbors paid him) he was one of their own.” The boy languished in bed, “day after day and month after month, three years he lay, while pain wrought ever, stealing, busy fingered, his strength away.” Whatever the disease or malady, it was crippling. The poem expands upon the cloistered life of the boy, and is detailed in the anguish of the family as they saw him slip slowly into decline. Confined to bed, “his pencil and his needle kept him busy over tints and forms.”

In all there are 22 stanzas in the poem and it is extremely well written. Someone took the time to sit with the family and create this ode to the young boy. It is both beautiful and sorrowful. As is so often the case when a child dies young, we fail to fully come to know the personality of what could have been. There are words of serenity and love in that small house and around the boy; the affection is astounding. But the sadness of his final days bring tears 155 years later. “Thus two slow summers passed, and then another, till one sweet day he whispered, ‘lay me back; I’m dying, mother’ and passed away.” As the boy passed from this world the bard writes of his moments of eternal rest: “His tired bent frame the first time straightened for many a moon, he breathed his soul out as the great sun heightened to autumn noon.”

There is little doubt that much of the community recognized the loss of this fair boy. The mill closed for the occasion of the funeral as evidenced near the end of the poem: “And silent all that day stood wheel and hammer in the old mill, and, all for love, rude men bred up in clamor walked sad and still.” The boy was taken to his final resting place in Maine.

In 1899, Jonathan Prescott celebrated a milestone birthday and the Boston Globe ran the headline, “Remains vigorous at 80, Jonathan Prescott celebrates birthday at home in Canton.” Interestingly enough, even at this point in his life, Prescott still worked for the Ames Company and was their “collector of rents” in Canton. The following year, the man who had commissioned the poem for his dear boy passed away after a bout with influenza. Harriet Prescott had passed away nine years prior — also of influenza. Father, mother and son are all buried together in a small rural cemetery in Mt. Vernon, Maine, within the Prescott family plot. The poem is in the collection of the Canton Historical Society.

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=68425