True Tales from Canton’s Past: China Trade

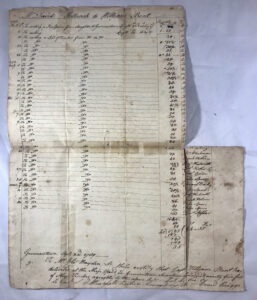

By George T. ComeauLemuel Fisher and Benjamin Wentworth had both served in the Revolution together. So it’s fair to say that like all veterans, they shared a common bond. After the war they both returned to Stoughton in that part which is now Canton and began to work the plow and the woodlots. In the spring of 1789 they were both completing the last of more than 40 journeys to Germantown, Braintree with heavy loads of freshly cut oak timbers. Fisher and Wentworth were helping to build a piece of history that would span the globe and set the course for trade in the centuries to come. These were only two of the men hired locally to cart timbers from the forests of Canton to the seaside of the Massachusetts Bay. Recently an accounting for timber from Canton was discovered in the collection of the Canton Historical Society. This scrap of paper unlocks a connection between what would become our community and Canton, China, offering a tantalizing story that may unlock another look at our place name.

In the late 18th century, a trip to what is now Quincy, but then was Braintree, would take a full day round trip from Canton. The trip to the coast would pass saltworks, fisheries, and a nascent shipbuilding empire. There was a healthy fishing industry concentrated at Germantown and great ships were being built in what would be the forerunner of the Quincy Shipyards. Daniel Briggs, from Pembroke and later from Milton, was building one of the greatest ships ever to be built in the country at the time. She would be the “Massachusetts,” and the plans for her were quite grand. In all, she would weigh over 791 tons and measure 137 feet by 36 feet and would rise 18 feet above the water line. The great ship was built by Briggs of a family that was prized for their shipbuilding expertise.

The client for the ship was none other than Samuel Shaw, an American Revolutionary War army officer and diplomat, who served as the first United States consul to China. Shaw was born in Boston. In 1775 he joined the militia during the Siege of Boston, and in December of that year was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Continental Artillery and commanded at Fort Washington in 1776. From 1779 to 1783 he served as aide-de-camp to General Henry Knox, chief of the Continental Artillery, in 1780 becoming captain of the 3rd Artillery, and serving in a staff role at the Battle of Trenton, Battle of Monmouth, and Battle of Yorktown. In 1784, after the war’s end, he sailed on the Empress of China as an American diplomat to inaugurate the China trade, and from 1786 to 1789 he served as consul at Canton. Shaw was part of the first generation of men who would start the China trade.

A new character was emerging in the personality of the United States — that of exceptionalism. Shaw believed that trade with the East Indies and China was the key to the economic prosperity of the fledgling nation. After several years abroad, Shaw settled in Boston and decided to make his own fortune trading with the east. In 1788, Shaw and a partner devoted close to $40,000 to build a great ship — the equivalent of over $1 million today. The risk was great, and the reward could be 10 times the risk.

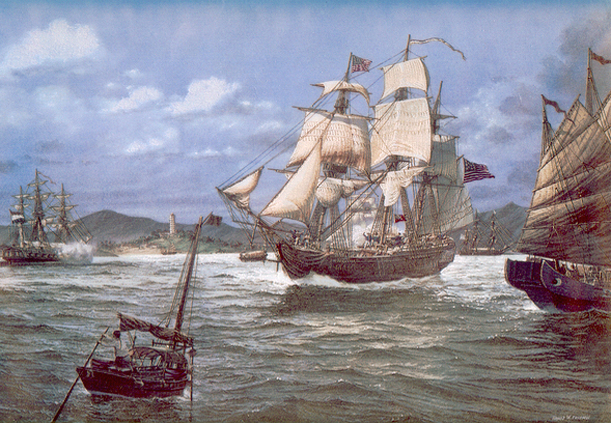

The ship “Massachusetts” must have been an amazing sight to see. If a modest-sized vessel, like what Shaw had been to China on previously, would yield great proceeds, imagine what a super-vessel could yield. The ship was described simply as having three decks, three masts, square storm, round house, double quarter galleries and figurehead. The men that came together to build the “Massachusetts” were all familiar to each other. The draughtsman was Captain William Hackett of Amesbury on the North Shore and he had built the Alliance frigate, which was the swiftest and most successful ship of the American Revolution.

The recently discovered document that traces the history of timber delivered from Canton to Germantown.

In turning to building the ship, the timber would come in great part from Canton. At the time, and it is so hard to conceive of it now, there were large “saw pits” located where the Canton Corner Cemetery is today. The remnants of these pits are still evident today in the landscape of this famous graveyard. The pit was owned by William Bent.

Bent was born in Milton in 1737 and died here in Canton in 1806 at nearly age 69. He had moved to Ponkapoag in 1763. Bent became a man of considerable local prominence. In the Canadian invasion of 1759 in the old French and Indian War he was a sergeant. At the time of the Lexington alarm he marched with Capt. Asahel Smith’s company but remained only a few days. He came back and recruited a company, at the head of which he marched on April 27 to Roxbury where he was ordered. In October 1775 he was in the 36th regiment Continental Army. During the war when not in service he purchased and delivered supplies to the families of the soldiers. For many years he kept the Eagle Inn and in leisure he was devoted to town affairs and church parish matters.

In the winter of 1788, Bent began delivering fresh oak timbers to Daniel Briggs. In the ensuing 40 trips over the next four months, a total of 1,795 feet of oak was delivered. Most critically, the earliest two deliveries were the keel pieces. Those timbers were sent in December and collectively weighed three tons — more than 6,000 pounds. When all was said and done, the oak from Canton became the frame for the “Massachusetts” on her trip to Canton, China.

You may be asking yourselves whether this historical tidbit has any bearing at all on the naming of Canton in 1797. To which the answer is likely a resounding yes. “It has been a matter of much conjecture why the town was so called. It has frequently been asked whether this name was petitioned for, and whether it was given to the town on account of the China trade, which was at the time of its incorporation becoming important?” To these questions a local historian of the late 19th century answered “no.” It has been the folklore of the story that the naming of the town was the whim of one individual, that of the Honorable Elijah Dunbar, who said that this town was directly antipodal to Canton in China, and for that reason should so be called. “This argument, fallacious as it was, served to convince those who probably had nothing better to offer; and so this name, unmeaning and without any historical associations, was adopted.”

The newly discovered document at the Canton Historical Society gives pause for a tighter understanding of the role we may have played in the trade route. William Bent was part of the committee to prepare the bill for the separation of Canton from Stoughton and many of the meetings were held in his tavern. To turn the phrase from Hamilton, Bent was “in the room where it happened.”

In 1789, the “Massachusetts” “slipt into her devoted element” in the presence of 6,000 people. Proclaimed “as perfect a model as the state of the art would then permit,” she took her departure under Captain Job Prince from Boston on March 28, 1790 at four o’clock in the afternoon carrying $15,000 in currency to trade and a hold full of provisions. As she passed Castle Island, the “Massachusetts” was heard saluting the fort with 13 guns and “was esteemed as fine a ship of her dimensions as ever went to sea.” From the ramparts of the castle the 13-gun salute was returned with pride.

By the time the “Massachusetts” arrived in Java and landed at Batavia, the capital of the Dutch trading empire, Shaw found that all trading had been suspended on account of “evil reports … by persons unfriendly to their commerce.” America was not yet a legitimate trading partner, and Shaw was in the unique place to repair this relationship. Having been appointed the U.S. consul to China by George Washington, Shaw set off to repair the trade issue.

The six months at sea had been corrosive to the mighty ship. The timbers that had been harvested in Canton were green and soft when placed in the water. The unseasoned oak, in the brine of the ocean passage, had deteriorated so badly that she was a loss on her arrival. This graceful ship built of unseasoned oak and loaded with soft green masts and spars had rotted. The ship’s hold had been sealed in Boston, and in the sail through the tropics the lack of air created a rot and stench that condemned her.

The second officer on the voyage wrote that of his observations, “The hatches caulked down in Boston, and never opened till we were in Canton. The air was then found to be so corrupt that a lighted candle was put out by it nearly as soon as by water. A mistaken idea prevailed at the time in regard to the best mode of preserving a ship and her cargo. There was prevented as much as possible air from circulating freely through the hold. Precisely the opposite of this ought to be practiced. We had between four and five hundred barrels of beef in the lower hold placed in storage. When fresh air was admitted so that the men could live under the hatches, the beef was found almost boiled, the hoops (from the barrels) were rotted and falling off, and the inside of the ship was covered with a blue mold more than half an inch thick.”

The loss to Shaw was great, and so the decision was made to sell the “Massachusetts” for $65,000 to the Danish East India Company that was trading in the port and had lost a ship in typhoon. The crew was set off to find their own way make to Boston. On December 4, 1790, the “Massachusetts” was sold to the Danes, and delivered up to them on December 10. “All hands went on shore to the bank’s hall to live, where they were daily decreasing; some going on board English ships, some onboard Dutch, and otherwise dispersing. So parted we with his noble a ship as ever swam the sea, and a set of us brave man has ever need be on board of any vessel.”

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=69513