True Tales from Canton’s Past: Forging Our History

By George T. Comeau

Lyman Kinsley’s home on Washington Street, altered and enlarged in 1840 and 1856 and destroyed by fire in the 1890s (Courtesy of the Canton Historical Society)

In a span of merely 20 years, Canton went from one of the busiest industrial communities in the commonwealth to a shuttered factory town. A small blurb in the Boston Globe in 1907 ran under the headline: “Will Be a Blow to Canton.” It was the passing of an industry, an obituary for a way of life for several generations of men from Canton.

There are very few, if any, vestiges of the Kinsley Iron & Machine Works that once existed on Washington Street. Built in 1788, the iron works was located where the water flows under Washington Street at the intersection of Revere Street. What we know as Forge Pond was the power for several companies that drew the water to turn the triphammers that in turn would stamp iron into bars, sheets, axles and rails. The earliest construction of railroads depended heavily upon several of the factories here in Canton. It is no coincidence that we have some of the first railroad lines in America.

Iron was one of the most important industries in 18th century America. The rise of the industry tracks closely with the growth of the nation. One scholar observed that iron’s “strength and durability made it a necessity of life and an item of increasing need with the growth of American settlement: nails, farming implements, guns, machinery components for burgeoning industry.” The British had prohibited any iron work in the colony with the exception of bog iron, which would have been sent to England for processing and refinement. The chokehold was soon broken and by the time of the American Revolution the colonies had become the third largest producer of iron in the world.

In the earliest iterations, the factories in “South Canton” had risen in the shadows of gunpowder and grist mills that had given way to blacksmith shops. The dam in the center of town was the site of a blacksmith shop built by Leonard Kinsley around 1760. Soon a partnership grew with Jonathan Leonard and the firm of Leonard & Kinsley was created. The Leonard family tradition of working and forging iron is the longest in American history. One historian wrote that “wherever you can find an iron works, there you will find a Leonard.” The first ironworks in Colonial America was built in Saugus in 1646, then in Braintree in 1652 and later in Taunton — all through the work and enterprise of the Leonard family.

Within 20 years the shop near the falls was producing farm implements, saw blades and tools that would be used in field and forest. By 1793 a slitting mill was in service that cut and rolled iron. In 1797 more than 1,000 tons of rolled iron made its way from Canton, carted by oxen to Boston and then onto distant customers. By 1821 the partnership between Leonard and Kinsley split and each took half of the mill — one on each side of Washington Street. A successive generation bought out the Leonard interest, and in the 1850s the Kinsley Iron & Machine Company was created.

The families prospered and new alliances spread into other steel families. Most notably was the connection between the Ames family from Easton and partnerships that arose in the mid 19th century with the Kinsley family in Canton. In 1858, Oliver Ames purchased the company and kept the Kinsley name intact.

Joseph Capper and William Morrison pose with a railroad axle, 1900 (Courtesy of the Canton Historical Society)

The factories of the Kinsley Iron & Machine Works straddled both sides of Washington Street. Large railroad trestles brought the grade height to match that of Canton Junction. The factories were noxious and blast furnaces roared at all hours of the day and night. Thousands of workers toiled in the dangerous conditions that were of fire and brimstone. The papers are freckled with stories of lost limbs, deaths and maimed men. By the time it shuttered its doors and was placed on the auction block, Kinsley Iron had produced guns for the War of 1812, railroad axles for thousands of trains and most of the shovels used for the western expansion of the United States.

When the Stoughton branch of the railroad was cut through Canton Center, several railroad spur lines crisscrossed Washington Street. There are a few vestiges of the retaining walls that once supported the spur line. An enormous fire in January 1875 destroyed much of the original factory on the east side of Washington Street. Almost a half-acre of building burned when a piece of iron was being sawed so rapidly as to send sparks into the wooden beams and flooring. The fire burned for hours and the loss was extensive. Within weeks the insurance claims led to a total rebuilding and modern equipment was installed.

Several final reminders were recently lost with the construction of the condominiums that now grace the small cul-de-sac just off Ames Avenue. In the heyday of factories downtown, several rail crossings had multiple intersections that were the sites of accidents, injuries and deaths. Not a week passed without an editorial in the local paper condemning the dangerous rail operations in the center of town.

A rather notable building that was lost in modern times connected to the iron industry was that of the old shovel shop on Bolivar Street that is now a ghost on the DPW facility grounds. The site had historically been a corn mill in 1792, and then a cotton factory from 1812 until a fire destroyed it in 1841. Lyman Kinsley purchased the site in 1846 and sold it to Oliver Ames soon thereafter. It has been surmised that Kinsley was a straw man for the Ames family and “an example of the subterfuge employed by the wealthy Ames family, here perhaps in an attempt to avoid the overpricing of the property which frequently occurs when a wealthy buyer is known to have an interest.”

Ames in turn built a magnificent stone building that was one of the last of its kind in Massachusetts. Jonathan French oversaw the extensive construction of the building, which was built against an earthen dam that held back Bolivar Pond. The “Shovel Shop,” as it was known, measured 170 feet long and 50 feet wide and had space for four hammers. The water power was further enhanced by building up three feet on the existing dam at that location. This building became the hammer shop used to plate shovel blades from iron and steel bars. The rough tools were hammered here in Canton and then carted to Easton to be finished.

The Ames Shovel Shop played a significant role in American history. During the period between 1867 and 1870 construction of the Transcontinental Railroad meant that the Shovel Shop’s employees worked overtime to make iron shovels for the Union Pacific project. Oliver Ames leveraged the fact that he was the president of the Union Pacific Railroad to funnel lucrative contracts to his own concerns and build upon a fabulous family fortune.

In 1927, the shovel shop was sold, and the Department of Public Works began using the building as a storage space. Right up until the beginning of the 21st century, the original water wheel and trip hammers remained intact. This was destined to be a National Historic Site as the “oldest surviving example of the Ames Shovel Company, and a rare example of an early iron forge building in Massachusetts.” Sadly, due to engineering concerns and the fact that it held the dam for Bolivar Pond, the building was demolished by the town of Canton and lost to future generations.

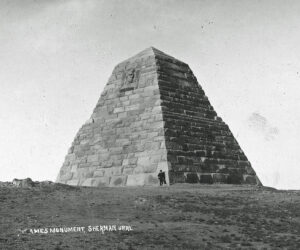

The Ames Monument at an elevation of 8,247 feet, standing at what once was the highest point on the route of the Union Pacific Railroad.

The iron and steel industry in Canton ended in 1909 in tandem with the end of the Revere Copper & Rolling Mill. Both factories and the extensive water rights were sold at the same auction. In the case of the Kinsley Iron Company, the stockholders withdrew their support and moved their investments into other opportunities. The iron business had long left Massachusetts and the competition with the great mills of Pennsylvania was another reason for the closing of the Canton mill. Wagon axles had given way to railway axles; hand shovels had given way to modern bulldozers and Canton was increasingly becoming a bedroom community. The products produced in Canton would be dwarfed by the needs of the enormous beasts of the 21st century. Quite simply, time had run out for the steel factories in Massachusetts.

Today, Canton Center is a beautiful tree-lined street, punctuated by quaint street lights and cobble-lined sidewalks. Condominiums now stand where mighty industries roared. Recently a beaver and a great bald eagle have made Forge Pond their home. River otters slip and slide on the ice flows; residents walk along the shore to spy a family of swans, and spring may surely bring their cygnets into view before long. The empire that the Kinsley, Leonard and Ames families brought to Canton only live in photographs and museum artifacts.

One final footnote. In Albany County, Wyoming, there is a large pyramid designed by H. H. Richardson and dedicated to brothers Oakes Ames and Oliver Ames, Jr., Union Pacific Railroad financiers. It marked the highest point on the First Transcontinental Railroad, at 8,247 feet. The products made in Canton and Easton as well as other family factories made the railroad possible and literally built a nation.

Few will remember that steel, copper and textiles were a key part in the evolution of modern Canton. The trip hammers and forges have been long silent. And to the thousands of ordinary men and women who worked in these dangerous places, we owe a debt of gratitude.

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=73470