Canton woman values connection to Vietnam

By Candace ParisThe Canton Citizen is pleased to partner with the Canton Diversity, Equity & Inclusion Committee to present “Community in Unity,” a monthly series spotlighting Canton residents of diverse backgrounds.

***

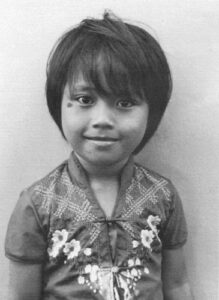

Canton resident Giang Le has learned over many years to walk the line between complete assimilation into American culture and attachment to her Vietnamese heritage. These days, she is comfortable with both parts of her identity, but this feeling did not come easily, requiring years of adjusting to change.

Le’s first big adjustment came as a young child, when her family became refugees from the hardships and repression of the regime that took power in South Vietnam following the fall of Saigon in 1975. Her father had fought for South Vietnam along with the Americans against North Vietnam, backed by China and Russia (then Soviet Union). Le said anyone who sided with the Americans fell under suspicion and was sent to a “re-education camp” for brainwashing; many died there. Imprisoned, her father was eventually released when her mother bribed the guards.

Together with an aunt and uncle, Le’s parents sought escape from Vietnam by boat for themselves and their three young daughters. “My father couldn’t see a future in Vietnam,” Le said. Many others chose the same solution at a time when secrecy was critical, and the “boat people” and the severe stress and dangers they endured became a well-known humanitarian crisis. The family’s first two attempts to board a boat failed, but on the third try, they found what they believed to be safe passage with over 300 other refugees.

Le, then only 4 years old, has only scattered memories of Vietnam and her family’s time on the boat. She does, however, recall the friendly fishermen who boarded the boat after it collapsed, causing many casualties. The fishermen talked to the children — but then turned out to be opportunistic pirates. (Piracy was one of the many dangers faced by boat people, in addition to thirst, hunger, sickness and drowning when boats proved unseaworthy. Some took their own lives when they lost hope, particularly if their family members died.)

A U.S. Navy ship, the USS Robison, luckily happened to be in the area and came to the rescue. “They were great people,” Le remembers. The 262 remaining refugees were taken to a camp in Malaysia, where the process to resettle them began. After a few months, Le’s aunt and uncle were sent to Boston, but Le’s mother was pregnant, so she wasn’t allowed to travel until after the baby was born.

In 1981, after nine months in the camp, Le’s family, now including her baby brother, traveled to Boston to live in Dorchester with her aunt and uncle. Le recalled being fascinated by the plastic tomato holders she saw in the supermarket. “They were the coolest toy,” she said.

Le’s father found work first in a factory and then operating a videotape business. From the time she was about 10 years old, Le helped out with the business. There were no vacations — the family thought that was only an American thing. “We always worked, and my Mom didn’t know how to have fun,” Le said. The hard work paid off, however, as the family eventually saved enough money to buy a house in Dorchester.

Surrounded mostly by black and Hispanic students in school, Le identified with them more than with her Vietnamese heritage. Another cultural rift occurred when, influenced by what they learned at a Protestant church and camp, she and her siblings refused to bow as customary for ancestor worship. Le’s mother, a serious Buddhist, burned incense every day for the ancestors. She directed Le and her siblings to “assimilate, keep a low profile, and mind your own business,” in contrast to typical American ways. She was too busy working, however, to emphasize the importance of maintaining their cultural connections.

After attending college for two years, Le dropped out and found jobs first in sales, then customer service, and finally in head-hunting, which she is still involved in working for her aunt. She married Rob Xayvethy, who is half Thai and half Laotian. In 2012, they moved to Canton; they now have four children. Two sisters, Jade Le and Hong Le-Smith, also live in Canton. (One sister lives in Quincy, her brother lives in Malden, and another sister is in San Francisco.) Le said, “I love the small community and the school system. All the parents know each other.”

Le and her family have not experienced anti-Asian attitudes in Canton. She did say that when asked where she is from, she is happy to answer but has noticed that people don’t like it when she then asks where they are from. Le said she’s been “shocked” by the current climate of violence against Asians. She has always encouraged her children to stand up for themselves when needed. These days, she worries about her mother, living in Quincy. She is in her late 60s and runs daily, and Le said, “She’s always aware, but I worry she could be caught off guard.”

Le and her family practice Christianity but also celebrate Vietnamese culture. Tet, the Vietnamese lunar New Year, is her favorite celebration. Occurring sometime between late January and late February, Tet, explained Le, is the “happiest time of year,” in contrast to the negative impression some Americans have from the Tet Offensive military campaign during the Vietnam War.

Le said she didn’t learn to love the Vietnamese part of her until her 30s, but she has tried to instill a strong connection to the culture in her children. Pre-pandemic, Le said, one of her daughters wanted to be more like her friends but “she’s now enjoying that she’s different.” Le has returned to Vietnam three times (she has relatives living there) and said she recognizes a few things like some fruit she didn’t even know she remembered. But America, she said, is home.

See this week’s Citizen for more photos from the 1980 rescue at sea courtesy of Giang Le.

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=74624