Canton’s True Tales: Another Ida May

By George T. ComeauThe small box looks like a miniature treasure chest. A skin of brittle leather covers the box, which is appointed by brass tacks. The original handmade lock is wrought from a blacksmith’s forge, and the entire box has an air of secrecy. Inside is a small glass photo trimmed in copper foil. This box was brought to the Canton Historical Society earlier this year and donated along with a few other items found in a house on Messinger Street.

Of greatest interest, aside from the box itself, is the small daguerreotype with a ghostly figure — that of a small girl. Now, usually photos of this sort come to the Historical Society without any information about the subject. There may be some provenance to help guide a historian to the family member in the photo, but unless there is a name inscribed on the back, then these are merely “instant ancestors” whose actual names are lost to time.

In this case, however, an intriguing note was inscribed on the back of the glass photo: “Ida May the white slave purchased by Hon. Charles Sumner and others of a Virginia Christian. Boston March 1855.” The clues were astounding and immediately linked the house in Canton with a family associated with the abolitionist Senator Charles Sumner. The clues led us to a remarkable story that is perhaps at the very genesis of the anti-slavery movement in America.

The mystery began to be solved by looking at the house on Messinger Street, which previously belonged to George Burt. Family history tells us that Burt was born in 1861, and his parents, who were not married at the time, sent him to Canton to be raised. Originally living on Dedham Street and brought up by a doctor, George would live his entire life here, and much of his time was spent in that house on Messinger Street.

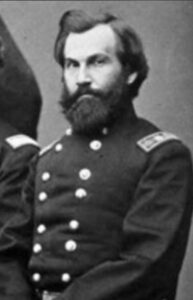

George’s father, William Lothrop Burt, was a powerful, influential, and politically connected man who had sway both in Boston and in Washington, D.C. Born in 1828 in Newburgh, New York, he graduated from Harvard College in 1850 and went on to earn his law degree from Harvard in 1853. Upon his death in 1882 at age 54, his obituary observed that William had been “quite an annoyance to his classmates at Harvard not only because of the no-holds-barred way with which he defended his abolitionist stance but because of his tireless activism on campus in support of the movement.”

After graduating from Harvard Law, William Burt gained notoriety for his defense of those arrested for their part in the badly bungled rescue of the renditioned slave Anthony Burns. At the time, he worked in the same law office as John A. Andrew, and when the Civil War broke out, Andrew became governor and appointed Burt as the judge advocate of the commonwealth of Massachusetts. Eventually rising to the rank of brigadier general, Burt spent time in every state of the Confederacy during the war and fought in various battles in the Gulf by land and water.

Burt was also lauded for his “indefatigable work while judge advocate general of Massachusetts, on behalf not only of the 54th but of other black regiments demanding equal pay to their white counterparts in the Union’s forces.” His obituary also notes that he “adamantly refused financial compensation for the time he spent in this military post during the Civil War.”

At the close of the war, Burt left office and went into business with Governor Andrew in Boston and was appointed postmaster in 1867. He also served for a time as president of the Utica Ithaca & Elmira Railroad and led the investor group that created the Boston, Hoosac Tunnel & Western Railway, making sure that women in his employ received equal wages as men.

The small box that contained the photo of “Ida May” was most certainly owned by William Burt. Here is a man who associated with all of the same people in Boston who were agitating to free slaves and provide them with safe passage and freedom. The prized photo passed to his son, George, at some point becoming a treasured family possession. But what of the purported white slave girl? That story is amazing and fantastic in its own right.

The story begins with a New York Times story from March 9, 1855: “We received a visit yesterday from an interesting little girl — who, less than a month since, was a slave belonging to Judge Neal of Alexandria, VA. Our readers will remember that we lately published a letter, addressed by Hon. Charles Sumner, to some friends in Boston, accompanying a daguerreotype which that gentleman had forwarded to his friends in this city, and which he described as the portrait of a real “Ida May” — a young female slave, so white as to defy the acutest judge to detect in her features, complexion, hair, or general appearance, the slightest trace of Negro blood.”

According to the Times story, the young girl’s name was Mary Mildred Botts, and six years earlier her father had escaped from the estate of Judge Neal and took refuge in Boston. He would later purchase his freedom for $600, but his wife and three children remained in bondage. Moved by his predicament, the newly freed man’s “Boston friends,” led by Charles Sumner, would secure the purchase of his family, settling on a sum of $800.

“They created quite a sensation in Washington,” notes the Times story, “and were provided with a passage in the first-class cars in their journey to this city, whence they took their way last evening by the Fall River route to Boston. The child was exhibited yesterday to many prominent individuals in the city, and the general sentiment … was one of astonishment that she should ever have been held a slave. She was one of the fairest and most indisputable white children that we have ever seen.”

In truth, the girl in the photograph was the lightest-skinned child of a black slave family, and Sumner, sensing an opportunity to advance the abolitionist cause, introduced her to the public as “another Ida May” — drawing parallels to the protagonist in Mary Hayden Pike’s antislavery novel, a fictional white girl who had been kidnapped and enslaved.

On February 19, 1855, Sumner wrote to his supporters about the enslaved 7-year-old girl whose freedom he had helped to secure. Noting that she would be joining him onstage at an abolitionist lecture that spring, he enclosed a daguerreotype of Mary standing next to a small table with a notebook at her elbow. Neatly outfitted in a plaid dress, with a solemn expression on her face, she looks for all the world like a white girl from a well-to-do family.

In her 2008 book Raising Freedom’s Child, historian Mary Niall Mitchell notes that this image of Mary Mildred Botts marked the “beginning of efforts to use photography … in the service of raising sentiment and support for the abolitionist cause.” Rather than the image that viewers might have expected to see in a photograph of a slave child, Mitchell said the public instead saw, in the daguerreotype of Mary, an image of an “‘innocent,’ ‘pure,’ and ‘well-loved’ white child who … needed the protection of the northern white public.”

This same photo is in the collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society as donated by the family of Governor Andrew, and there are only three known surviving copies. The idea to have Mary’s daguerreotype portrait made may have begun with Governor Andrew. In a letter to Sumner, he wrote that he wanted the legislature to “have a sight of those children, in the hope that their presence may add impressiveness to the appeal made for state action” regarding the Fugitive Slave Law.

We know that several of the photos were made to help raise money and awareness of abolitionism. The one owned by William Lathrop Burt is especially wonderful because of his associations to the cause — and presents yet another example of the rich history of this community on a national stage. George Burt was a member of the Canton Historical Society and was also one of our earliest photographers. We are grateful to the Burt family’s descendants for sharing their history with the town.

The “Ida May” photo and other Burt family items were donated to the Canton Historical Society and are a treasured gift that stands for the greatness of a Canton family that helped chart the course of American history.

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=124298