True Tales: Patriot’s Day & Divine Providence

By George T. Comeau

The 1886 Fast Day Walk at the York Street Schoolhouse. (Photo courtesy of the Canton Historical Society)

Monday is one of those “half holidays,” meaning that half of us get the day off and half of us work. Hardly anyone can fully explain the holiday today — Marathon Monday, Patriot’s Day, or the day when one is absolutely certain that the Red Sox will be playing at home.

Patriot’s Day commemorates the opening salvo in the American Revolution at Lexington. Interestingly, though, the holiday was a spiritual one whose traditions dated back to the early pilgrims at Plymouth. Today we know it as Patriot’s Day, but prior to 1894 it was known as Fast Day.

Fast Day, as the name suggests, was a day for introspection and piousness — a day set aside for devotion to the Lord and to give thanks for the providence his hand set upon the colonies.

To place Fast Day in perspective, the earliest known printed order of the government calling for a specific day reads: “The council taking into their serious consideration the low estate of the churches of God throughout the world, and the increase of Sin and Evil amongst ourselves … do therefore appoint the two and twentieth of this instant September to be a day of publick humiliation throughout this jurisdiction … hereby preventing all servile work on that day.” This Fast Day Proclamation was made in 1670 and soon became a common occurrence.

In that part of Stoughton that is now Canton at First Parish Church, fasting days were observed and carried out religiously. In 1718 the records of the church note: “It was agreed upon to set apart a day for fasting and prayer and to hold it in public in ye meeting house, for to seek the Lord’s favor and the smiles of His Continence to rest upon this church and Congregation.”

Over the course of Canton’s history, various days were called for fasting for all manner of reasons: to relieve great sicknesses that befell the community, to promote peace between the minister and the elders, for a cessation with the War with Spain, for the defeat of General Braddock’s Army, for rain, and for relief from smallpox.

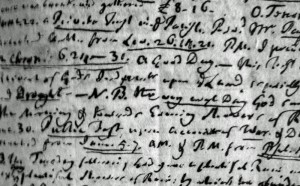

Parson Samuel Dunbar, the minister in Canton, was by far the most faithful believer in the power of a fasting day. At the Historical Society there is a small, brittle diary that is over 285 years old. In an unbelievable tightly written hand, infinitesimally small handwriting scratches out the following entry from June 1757:

An entry from Samuel Dunbar’s diary detailing the observance of Fast Day in 1757. (Photo by George Comeau)

“A private fast was held on June 22, 1757, on account of God’s Judgment upon the land, especially war and drought. The very next day God sent us in the morning and towards the evening showers of rain. On June 30 the same thing was tried again; a public fast was held on account of the war and drought, and on Tuesday following God gave a plentiful rain, and the next day plentiful showers of rain, by which he abundantly watered the earth.” No word on whether God intervened with the war efforts.

The historical records are full of instances where the government and the church ordered fasting days to give thanksgiving or to offer sacrifice in order to improve conditions within the town. While starting as purely religious in nature, the early days were marked by the need to recognize “divine providence.”

Through the American Revolution this same spirit of beseeching God’s intervention in the war carries throughout the local record. Public fasts to support the fight against King George were common occurrences. After the revolution, and with the establishment of a federal and state government, the observance became “infused with public spirit.”

As you read this, you no doubt wonder about the connection between the separation of church and state; in fact, the real problem came between the separation of the federal and state governments and not the church at all. Curiously, President George Washington, as leader of the federal government, called for an annual day of fasting and thanksgiving. But in Massachusetts, the architect of liberty himself, Samuel Adams, declared a day of thanksgiving without mention of the fact that the federal government had actually called for the day. This omission and bold streak of independence in Massachusetts caused a huge controversy.

Fast days continued throughout the 1800s, and in Canton the day took on a new significance in 1874. The Canton Historical Society organized in May 1871 with the express desire to “treasure up all the old traditions from the time of the Indians to the present day.” The first president was Daniel T.V. Huntoon, the eminent local historian who, along with Frederic Endicott, was instrumental in organizing annual Fast Day walks…

See this week’s Canton Citizen to read more on the history of Fast Day walks in Canton.

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=12946