True Tales: Thoreau’s 6 Weeks in Canton

By George T. Comeau“Dear sir. — I have never ceased to look back with interest, not to say satisfaction, upon the short six weeks which I passed with you. They were an era in my life — the morning of a new Lebenstag. They are to me as a dream that is dreamt, but which returns from time to time in all its original freshness. Such as one I would dream a second and third time, and then tell before breakfast.”

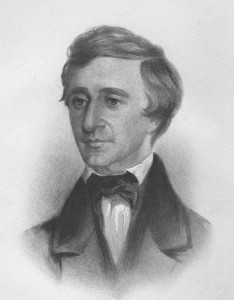

Such opens a beautiful and sincere letter from none other than Henry David Thoreau as he recalls six weeks in Canton. These six weeks were critical in the development of the mind of one of America’s most influential authors and poets. Thoreau’s time in Canton was more than simply a casual break from life at Harvard; it was likely the first of a long line of exposures to new thinking that would transform Thoreau into a leading transcendentalist.

In the fall of 1835, there were six district schools in Canton. Each district had a small schoolhouse and separate school committeemen elected to oversee the educational program. The previous April, at a meeting held in the Baptist Meeting House, the town elected Thomas French, Esq., as one of the committeemen for the school located near Canton Corner. French writes that it was an “honor and happiness to live in an era memorable for its efforts in the cause of a common school education.”

French was as influential as you could get in the early 19th century life of Canton. Serving within a variety of capacities, he embraced public education and supported the Canton Lyceum, the Literary Association, and was a guardian to the Indians. Most important, however, he was the leader of the Parish Committee of the First Unitarian Church. And in assessing the capabilities of the 19-year-old Thoreau, French turned to Reverend Orestes Augustus Brownson, who held sway over all that was spiritual, and valued his opinion in the examination of this prospective teacher.

Brownson was installed as pastor in May 1834 and from the start was a firebrand with an unorthodox and independent view that did not settle well with all of Canton’s citizens. From the pulpit, Brownson advocated for fundamental social reform. In an 1834 Fourth of July address, for instance, he expressed concern that economic inequality was growing and noted that the nation was failing to live up to the principle of equality embedded in the Declaration of Independence. Brownson’s social radicalism alienated some of his parishioners. When his contract was renewed in 1836, ten church members voted against his retention. In what would be a short tenure at the First Parish, Brownson instead would leave an indelible mark on Thoreau.

After learning that he would be hired for a term in Canton, Thoreau wrapped up his junior year at Harvard early in December. College records say briefly: “Gone to keep school,” meaning that he would be away from Cambridge until March 20, 1836, that being the entire quarter. Leaving Cambridge on December 3 or 4, Thoreau “seems to have gone immediately to Concord, perhaps to remain at home until after Christmas.” Like all college students — even today — Thoreau had to complete a few overdue assignments. One assignment was for a course on Moral and Intellectual Development, and a second was submitted as an English composition for credit on the first-year term.

Within a few weeks, however, Thoreau would turn from being the student to becoming a teacher of 70 in a one-room schoolhouse. Noted historian Kenneth Walter Cameron researched Thoreau’s time in Canton and was the definitive authority on the subject. As to when exactly Thoreau spent his six weeks in our town, Cameron writes, “I suspect in January and February 1836, that is, following Christmas and at the beginning of the last five months of Brownson’s pastorate in Canton.”

While we know definitively that Thoreau was here for six weeks, he may have been here longer. The fact is that while Thoreau was here, Brownson was in the center of a tumultuous spiritual awakening in the community and the church.

Brownson has been described as a maverick Universalist and Unitarian minister. According to the Dictionary of Unitarian & Universalist Biography, “The independently minded journalist, essayist, and critic was a wide-ranging commentator on politics, religion, society, and literature with connections to the Transcendentalist movement.” In a time of great political and economic unrest, Brownson believed Christianity must lead the fight for social justice, and he publicly declared Jesus “the prophet of the workingman.”

Rev. Brownson, the seventh minister of the First Congregational Church in Canton (Library of Congress, Washington D.C.)

It was against this backdrop that Thoreau moved into the house on Pleasant Street to board with the Brownson family. A letter from Thoreau to Brownson in 1837 implies he spent six weeks in Brownson’s home. Thoreau may have taught for a longer period in Canton, while boarding with another family. The entire span that year for the winter term was around nine or ten weeks. So it is possible he stayed longer or was merely a substitute for another teacher.

Today, the house that Thoreau boarded in is a tidy and beautiful example of period architecture almost opposite the Pequitside Farm. Known historically as the “Jordon House,” it was built on an elevated ridge just above the center of Canton Corner. Built by the Reverend Henry Edes in 1832, it was nicknamed “The Egg.” In one room is a “Bible Closet” where the original owner stored his ecclesiastical books. Even today, this is a grand house and must have been impressive in 1832. The home is graced with roman columns, paneled walls, delicate door casings, and eight fireplaces with ornate detail.

Owing to the fact that the house was built originally for Reverend Edes, an upstanding minister with a fire in his belly against the sins of liquor, there is yet another nickname for this house: “The Whisky House.” Legend has it that to set a good example for his neighbors, Mr. Edes declared that there would never be any rum in his new house. The builders, however, unlikely teetotalers themselves, promptly sent to the store for a pint of New England rum. Hidden behind the plaster walls is a two-century-old spirit that has never been found. On the third floor of the Jordon House is likely where Thoreau lived. The view would have been commanding and presenting a “wide horizon for his thoughts.”

The connection between Thoreau and Brownson in Canton is an amazing part of the story. While with the minister, Thoreau studied German and would undertake a more serious study of the language in his senior year late in 1836. It is such that Brownson convinced Thoreau to “study the language in earnest as a vital channel of transcendental truths from abroad.” When Thoreau refers to his time in Canton as “the morning of a new Lebenstag,” he is giving credit to Brownson for raising his interest in philosophy and metaphysical poetry. Within a year of spending time with Brownson, Thoreau saw his vocation as leading the life of a poet and drinking in the “soft influences and sublime revelations of nature.”

While in Canton, Thoreau would have certainly attended meetings of the Canton Lyceum held at the old part of the tavern in what became the Massapoag House in South Canton. Lectures were given by learned men on such subjects as “Is Slavery on any Principle Justifiable” and “Which is the Greatest Influence on Society, Wealth or Talent.” Brownson delivered many of the lectures — one on “Female Education” and another on educational principles.

The Jordon House on Pleasant Street, where Thoreau boarded in 1836 (Courtesy of the Canton Historical Society)

After the Canton experience, Thoreau returned to Concord and in due course to Harvard College. A changed man under the Brownson influence, Thoreau became rebellious toward organized religion. A close friend, Amos Perry, noted a profound change in attitude: “Thoreau’s figure seems to me as distinct as if I had seen him yesterday … In his junior year, he went out to Canton to teach school. There he fell into the company of Orestes A. Brownson, then a transcendentalist. He came back a transformed man. He was no longer interested in the college course of study. The world did not move as he would have it. While walking to Mt. Auburn with me one afternoon, he gave vent to his spleen. He picked up a spear of grass saying: ‘Here is something worth studying; I would give more to understand the growth of this grass than all the Greek and Latin roots in creation.’ The sight of a squirrel running on the wall at that moment delighted him. ‘That,’ said he, ‘is worth studying.’ The change that he had undergone was thus evinced.”

That Thoreau was transformed in Canton by Brownson’s idealistic views is evident in both men’s writings that have survived to this day. Canton itself was not transformed, however. Brownson gave his notice to the church that he would depart in May for a larger ministry in Boston. In 1844 he converted to Roman Catholicism and became a Catholic intellectual, a constitutional conservative, and a fierce critic of Protestantism.

Thoreau returned to Harvard, eventually becoming a teacher. Having finished university, Thoreau taught in Concord to earn a living. It was a position that furthered his rebellion. When ordered by the principal of his school to use corporal punishment to maintain order, Thoreau demonstratively told several of his students to step forward, gave each of them a symbolic slap, and resigned. In case one should wonder where Thoreau gained this view on corporal punishment, Brownson’s view on the very subject is thus: “I am convinced that a man who is fit to teach a school will never have occasion to strike a child.” Thoreau was just that man.

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=24429